Event Horizon’s Scariest Scene Has No Blood, Guts, or Gore

Where we're going, we won't need eyes to see Event Horizon's spookiest moment.

Critically-panned box office flop Event Horizon is now considered a space-horror classic, with many of its gruesome scenes becoming iconic since its 1997 release.

Interestingly, the cut of the film we got was much less violent than its director intended. Around 30 minutes of footage was trimmed after the studio and test audiences found the first version simply too horrific, but there are still enough disturbing moments to pack a punch.

If you close your eyes (you won’t need them to see), you might be able to pick out a few of those moments from your own mysterious core right now. Sam Neill’s Dr. Weir, his face all torn up. Chief Engineer Justin, clutching desperately as blood pours from his eyes in the depressurized airlock. D.J. vivisected on the operating table. Then there’s the video retrieved from the log of the Event Horizon’s original crew, which includes the captain holding his own eyeballs in his hands and all manner of other nasty crap.

Good stuff! But the scariest scene in Paul Anderson’s cult sci-fi gem doesn’t need any of that to shit you up. No blood, gore, or guts. It’s what we don’t see that’s terrifying.

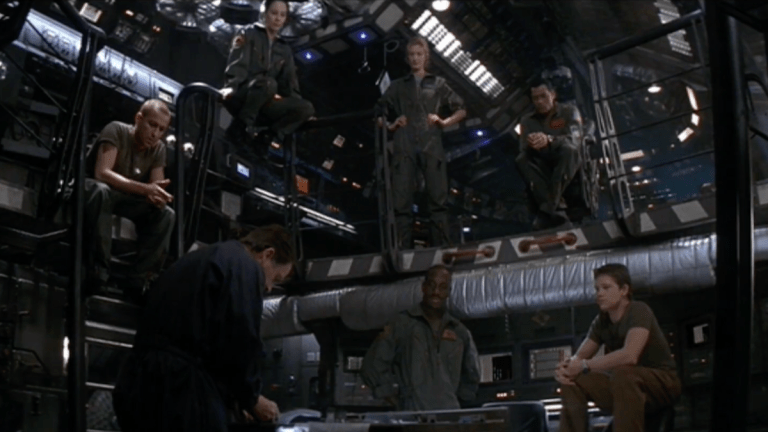

Anderson sets up the scene by gathering the crew of his reluctant rescue ship, the Lewis and Clark, to hear some lengthy exposition from Dr. Weir, who originally designed the Event Horizon and wants to explain how she travels in space. The crew jokes around and trades friendly barbs in their brightly lit quarters. We’re told that the Lewis and Clark is running perfectly before being introduced to them one by one, culminating with “gloomy Gus” D.J. (Jason Isaacs), who seems more downbeat than the rest.

The Event Horizon has been missing since its maiden voyage to Proxima Centauri seven years ago, and uses an experimental gravity drive to fold spacetime and travel vast distances, Weir tells them. It has now mysteriously popped up in orbit around Neptune, so the Lewis and Clark has been sent to investigate its distress signal.

Now that we understand who these people are and what they’re all doing here, Anderson cuts to a scene where Weir is ready to play the Event Horizon’s distress signal to the crew. This transpires in a deeper, darker part of the ship’s bridge. The bright lights of the previous scene are gone, replaced by blinking computer screens, glowing buttons, and shafts of light streaming from overhead fans.

With his back to the camera, Neill’s troubled Dr. Weir quickly leans forward and plays the transmission received from the Event Horizon. If it’s not a collection of the worst sounds you’ve ever heard in your life, it could at least make the top ten. Howls, screams, and a low voice uttering some desperate words.

“What the fucking hell is that?” asks Sean Pertwee’s pilot, Smitty, who speaks for all of us. Weir responds by isolating the human voice in the recording, and D.J. translates it from Latin as “Save me.”

There’s no ominous score accompanying this short scene. Just the hum of the ship’s engine and the terrifying audio from the Event Horizon being played repeatedly. After D.J. translates it, a loud alarm interrupts the conversation, and the crew scramble to their stations. They’re about to get a taste of the journey that the Event Horizon has been on. Only a few will save themselves from Hell.

Anderson doesn’t need to show us any visual nastiness to provoke the kind of dread that the distress signal effortlessly evokes. Our imaginations do most of the work, conjuring up explanations for why the crew of the Event Horizon would scream like that. None of the Lovecraftian horrors that we see later can match the sheer terror of the unknown, however gross.

We are wired to fear uncertainty because unpredictability makes it harder to plan and prepare for what might happen next. Plenty of scientific studies show that people experience more stress in situations where the outcome is unknown than in ones where they know they’re going to face something bad. This uncertainty triggers alarm responses in the body and mind because we prioritize safety and quick reactions to potential threats, so the unknown feels like a risk even when the actual danger is low.

It’s likely just an evolutionary development to keep us out of harm’s way, but the horror genre is very good at using it against us. It’s why we never see the witch in The Blair Witch Project, and why Alien and Jaws try to keep their monsters hidden or confined to the shadows for as long as possible.

The Event Horizon’s distress call puts us in a stressful holding pattern within the first 20 minutes of the film. What follows is upsetting and often disgusting, but our fear never reaches the same heights as it does in this scene, which uses its genius sound design to set the stage and scare us into submission.

Where we’re going, we won’t need eyes to see.