Virtual Reality: From The Lawnmower Man to Ready Player One

A potted history of VR from its video gaming roots in the 90s through to where we are today...

This article comes from Den of Geek UK.

The nineties. What a decade it was. Cyberspace, the wistfully conceived ideal of a shared digital domain that the entire world could interface with, was finally birthed properly into reality, despite seeming like a pipe dream when cyberpunk author William Gibson first conceptualized it a decade earlier. Information shed its physical form, digital cameras and MP3s appeared. For the first time, humanity began to seriously wonder, as the millennium drew closer, if one day we too might divest ourselves of these limited fleshly raiments and enter an eternal digital nirvana where we would live forever, with our every whim satisfied with but an electronic pulse of our messianic minds.

Plus, there were shell suits and Global Hypercolor t-shirts, too. What a time to be alive.

The advent of digital media, the proliferation of the world wide web, and clothing that actually turned your pubescent sweat pangs into neon tie-dye weren’t the only harbingers of a revolution that would change the face of the world. The early ’90s also witnessed the first real consumer-facing virtual reality products, and while the impact of VR cannot yet be considered in the same league as the other three innovations, its refusal to lie down and die, despite being written off as a gimmicky flight of fancy more times than you can count (or at least, more times than you could wash a Hypercolor t-shirt before it became a mushy brown mess) means that as of right now, VR’s profile has never been higher.

Recently showing the world over and prompting all manner of interesting conversations (if perhaps, not a great deal else), Steven Spielberg’s Ready Player One exposed the masses to the idea of a future where VR hasn’t just become an important part of people’s lives, but has transformed into something that people measure the importance of their lives by. That’s a dystopian twist that, let’s be honest here, doesn’t seem all that much of a stretch given how the video gamers among us are prone to eschewing the real world in favor of grinding out hours within a virtual space to attain a shiny new bauble for our beloved avatars. And yes, I am speaking from experience there. Far too much of it in fact.

So, with the uninviting future that Ready Player One posits looming darkly on the horizon like that portentous storm at the end of The Terminator, we thought we’d cheerfully bury our heads in the sand (metaphorical, not virtual) by instead looking backwards, providing you with a potted history of VR, before it teams up with AI to form a humanity-enslaving supergroup with an unpronounceable acronym.

Despite existing notionally in various forms throughout the twentieth century, virtual reality as we know it was first fully realized in the 1980s. Although work in the field had been developing for decades, with the first head-tracking goggles created in the 1960s, it wasn’t until the mid-1980s and the proliferation of powerful personal computers, alongside the emergence of Silicon Valley, that the technology evolved to the point where it fully resembled the consumer-facing tech we recognize today. Predecessors to the haptic gloves and suit sported by Wade Watts in Ready Player One reached the market at this point too, and despite being prohibitively expensive (a single glove cost $9000!), the technology began to gain a foothold in the market. Presumably, because they thought cyberspace was an oddly-named corner of the cosmos that they’d somehow missed, NASA was one of the biggest proponents of the new tech, along with it being used for medical applications and flight simulators.

But what of the games? If anything, it’s VR’s potential in the video game sphere that has most often reanimated the technology’s oft-cooling corpse and set it shuffling once more from the hypothetical towards reality. With its oh-so-cool holodeck, if Star Trek: The Next Generation taught us anything during that halcyon era, it was that one day holograms or some sort of technology would improve to the point where we’d be unable to distinguish entertainment from reality, sort of like Westworld but with less robot slavery.

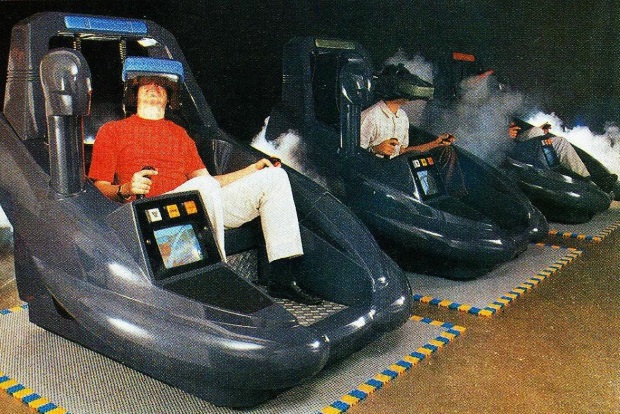

The ’90s wave of VR games really kicked off with the rise of Virtuality, a UK-based company that pioneered the tech and carried it into arcades. Although looking back at the tech now makes it seem amusingly clunky, one has to remember that creating this level of three-dimensional immersion was pretty impressive given that some of us were only just jettisoning our two-color ZX Spectrums by this point.

Games included Dactyl Nightmare, a competitive multiplayer first-person platformer where you could get picked up and swooshed off by a pterodactyl at any given moment; Total Destruction, a stock car racer; and even Pac-Man VR as later iterations of the hardware improved. I remember trying the tech out for myself at GamesMaster Live at the NEC in 1994, queueing for what felt like hours to play some kind of WWI-era flight simulator for a scant few moments, but I’ll never forget the experience of being able to turn around 180 degrees and look at my co-pilot in the bi-plane, a quite singular moment that has never left me. Sure, the graphics were basic and the controls clunky, but in an era where home systems were struggling to faithfully recreate the noise and bombast of arcade coin-op experiences, the technology that could actually replicate reality, no matter how nascent it might be, had more than a whiff of sorcery about it.

Despite firing the public imagination and spawning movies like The Lawnmower Man (1992), the first VR boom didn’t last. Sudden and rapid advancements in home console technology, such as Sony’s first PlayStation console, offered high-end gaming experiences from the comfort of your own home and so the arcade, the fabled Shangri-La of gaming, fell into history (as we wrote about recently) taking the emergent VR tech with it. The situation wasn’t helped by Nintendo and Sega, the major industry giants of the era, both taking a giant swing at establishing home-based VR systems and missing wildly. Nintendo’s Virtual Boy is considered to be one of the greatest hardware misfires of all time, while Sega’s imaginatively-titled Sega VR never even really made it to market, canceled eventually because the company claimed the experience was too realistic. Of course it was, Sega. With rumors of motion sickness and splitting headaches circulating, and genuine concerns as to what effects long-term use of the device could engender, that excuse seemed to borrow more from the virtual than from the reality if you ask us.

After that, things went quiet for over a decade. Virtual reality, it seemed, had enjoyed its moment and continued only as a sci-fi construct, spawning clever concepts like The Matrix and Existenz (both 1999). But ideas, as they say, are bulletproof, and this one refused to die. As technological leaps between home console iterations began to slow down towards the end of the last decade, Joe Q. Public it seemed was once again hungry to experience something more than an increased pixel count and the promise of a faster processor. When Palmer Luckey launched a Kickstarter campaign back in 2012 to raise $250,000 with the aim of bringing virtual reality back to the market in the form of Oculus Rift, the response was overwhelming. The project was backed to the tune of over $2.5 million and a few years after that, Facebook paid billions to acquire the startup company. HTC, Sony, Google, and a host of other companies followed suit, and suddenly VR was an overnight phenomenon thirty years in the making.

Perhaps a case of the possibilities of technology finally being able to better align with the power of imagination, VR’s second coming seems to have created experiences that finally prove the validity of the medium. My second VR experience occurred twenty-three years after my first, in a VR tent at the Edinburgh Fringe, and it was one of the most moving storytelling experiences that I’ve ever encountered. Hooked up to an Oculus, watching (for the want of a better word) a short VR film entitled Dear Angelica, I encountered the transcendent power of virtual reality. Experiencing a story unfold around me in three hundred and sixty degrees was not only more immersive than most films I’d ever seen but in itself presented new modes of spectatorship.

Film theory has posited the concept of body mimicry before – that the viewer physically mimics the actions on screen, tightening their muscles in tension or flinching in terror – but experiencing a film in VR goes beyond simple replication into so much more. Immersion. Choice. Tactility. As the story unfolded around me on all sides, the power to decide where to look was intoxicating, as was the film’s ability to create moments of such imagination, such levels of childlike wonder that I was left breathless, both laughter and a few tears escaping me in a dizzying, cathartic rush.

With virtual reality very much part of the mainstream consciousness again, developers are doing more and more to push the boundaries of what a VR experience can be, so much so that already the technology sported by Wade Watts in Ready Player One is very much here. Most VR developers are already developing wireless technology (HTC’s has already arrived) and shedding systems of those immersion-breaking cables. 4K displays are not too far away and the haptic suits that give real-time physical feedback are already on the market, as is something resembling the omni-directional travel mat that replicates the feeling of unimpeded movement.

And what of the games? The interactive experiences that have driven much of VR’s evolution continue to become more and more ambitious. While gaming on home systems such as the HTC Vive and PSVR continue to offer a wealth of experiences (some abject, some unmissable), it’s the rise of destination-based gaming experiences that has really raised the bar for the medium, offering experiences that are moving steadily closer to that fabled holodeck experience that was once but a distant dream.

Ironically enough, for a medium which lost vital momentum the first time around due to the sad demise of the amusement arcade, these VR gaming experiences have now become entertainment destinations in themselves, places that people venture to experience the types of gaming encounters that they cannot reproduce in their homes. The recent Star Wars: Secrets of the Empire VR installation in London was one of these hotspots, attracting curious Star Wars pilgrims from across the nation to experience A Galaxy Far, Far Away in a form offered almost nowhere else (there are only two of these attractions worldwide).

Developed by ILMxLAB (Lucasfilm’s VR and AR division) and The Void (an American bleeding-edge VR company), the game is set in the Rogue One timeline and markets itself as “hyper reality” and with good reason: in the same fashion that cinema’s 4DX augments what’s happening on the screen with artificial wind, rain, heat, and lightning, hyper reality is VR that assaults your senses in blistering fashion.

Let me give you an example: early in the experience, you and three other hardy rebels are disguised as stormtroopers, charged with bluffing your way into the Imperial base on Mustafar to acquire a top-secret weapon that could aid the fledgling rebellion. As you leave the relative safety of your stolen Imperial shuttle, the four of you board a small skiff and speed over a vertiginous drop, with the bubbling lava (that makes Mustafar the ideal destination for holidaymakers and Dark Lords of the Sith alike) radiating a terrible heat from below. Put simply, it is masterful game design. The perilously small dimensions of the skiff mean that the four of you are never comfortable as it hovers over the deadly expanse of liquid magma. You have to keep looking down to ensure you aren’t about to fall off… and looking down means seeing the very thing you don’t want to see: scorchy red death sea. It’s guaranteed to make your stomach flip, more so because the intense heat that’s actually being radiated upwards further fools your senses, telling your brain that the peril that your eyes are encountering (in crisp 2K graphics) may just be real because the touch department has just been on the blower and confirmed that yep, they can feel it too.

It’s a great moment in an experience packed full of them. More than that, it’s suggestive of just where the long-term future of gaming may lie. With this console generation seen by some as something of a disappointment thus far, one wonders just how far the current model of incremental improvements can sustain hardware manufacturers before there’s a market decline, especially in the face of growing competition from other platforms like VR and mobile gaming. Once they figure out how to bring an experience like Secrets of the Empire to your living room (and they always do, eventually), then it might be TV-based gaming that goes the way of the arcade cabinet.

Imagine it: one day far in the future we’ll put down our 8K visors, turn off the OASIS (or whatever fancy name it might have), and travel out to a sparsely occupied amusement arcade to enjoy the quaint pleasures of the PlayStation 7, all the while commenting on how positively archaic it all feels. Unlikely? Yes. Impossible? Far from it. With VR coming back from the dead more than once, there’s a good chance that, like zombies or Hypercolour T shirts, world domination is less of a likelihood and more of an eventuality.