Arcade Perfect: The Lost Era of the Coin-op Conversion

They were often a pale imitation of the original, yet home conversions of hit arcade games were a big deal in the 80s...

This article comes from Den of Geek UK.

Even if you weren’t around in the 80s and 90s to enjoy them first-hand, games of that era are so commonly evoked in the 21st century that you’re probably aware of what they looked and sounded like. Hit indie games like Shovel Knight and Fez reference back to the lo-res graphics and two-button gameplay of the NES and SNES era. Movies like Wreck-It Ralph and Pixels channel the spirit of such arcade classics as Pac-Man and Galaga.

There’s one aspect of 80s and 90s videogame culture, meanwhile, that is in danger of being forgotten: the strange phenomenon of the coin-op conversion.

It’s hard to imagine now, but there was a time when the technological prowess of arcade games frequently outstripped what was available in the home. The competitive, fast-paced world of the amusement arcade meant that developers like Atari, Namco, and Sega were regularly updating the hardware that underpinned their games – all the better to give potential customers bigger, more eye-catching arcade machines designed to relieve them of their spare change.

Arcade developers were also racing against the increased competition from computer and console manufacturers – to lure gamers away from their Atari 2600s and back into arcades, designers had to come up with flashy games that couldn’t be experienced anywhere else. One version of Atari’s Star Wars, for example, came housed in a sit-down cabinet with booming stereo sound; Sega’s AfterBurner had a pneumatic seat that through the player around in synch with the on-screen action.

All the same, there was a hunger among some gamers to the best of these arcade hits home with them – which is where the coin-op conversion comes in.

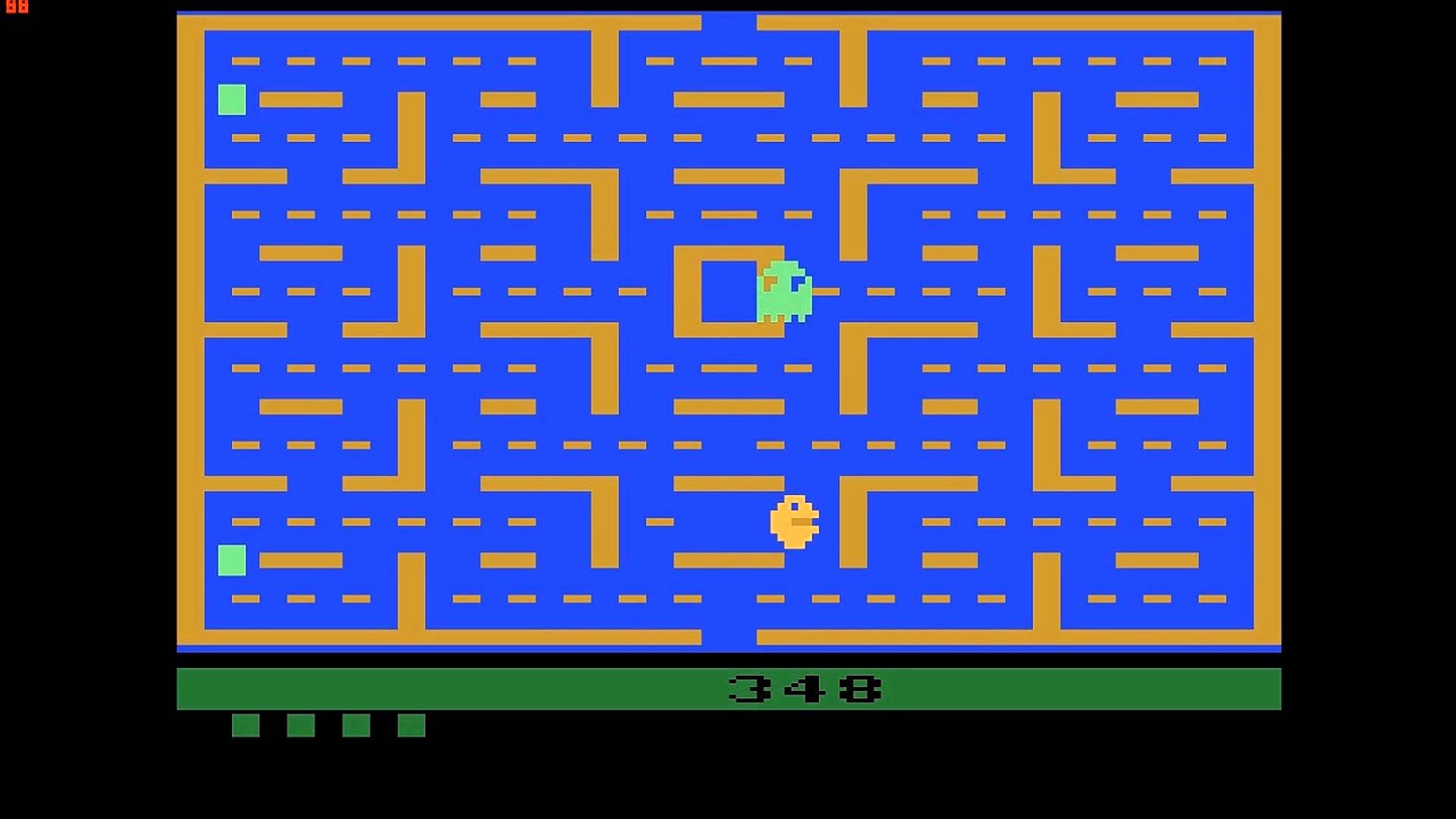

Even in the early days of home computers and consoles, there were adaptations of popular arcade games. The Atari 2600, despite its meagre hardware, played host to ports of Space Invaders and Asteroids, Centipede, and Defender. In many instances, the original game had to be compromised in several ways to fit the system’s limited capabilities, with redrawn characters or simplified level designs. In some instances, the results were pretty terrible – the 2600 port of Pac-Man barely resembled Namco’s arcade game at all.

Ports of arcade games were fairly hit and miss, but the demand for them remained high. This may have been partly because of convenience: there was a certain thrill at having a version of Pac-Man you could play in your own home. Besides, not all of us lived near a decent amusement arcade, so simply having a home computer version of Operation Wolf or Space Harrier that looked and sounded passably like the real thing was an exciting prospect.

In some cases, these ports required a fair bit of imagination on the player’s part. The ZX Spectrum version of Sega’s racing classic, OutRun, for example, couldn’t hope to recreate the coin-op’s spectacular music, so the home version came with a separate audio cassette that you could put on while you played the game. Enjoying OutRun on the Spectrum was the 8-bit equivalent of play-acting: it took a bit of effort from the end user to really work.

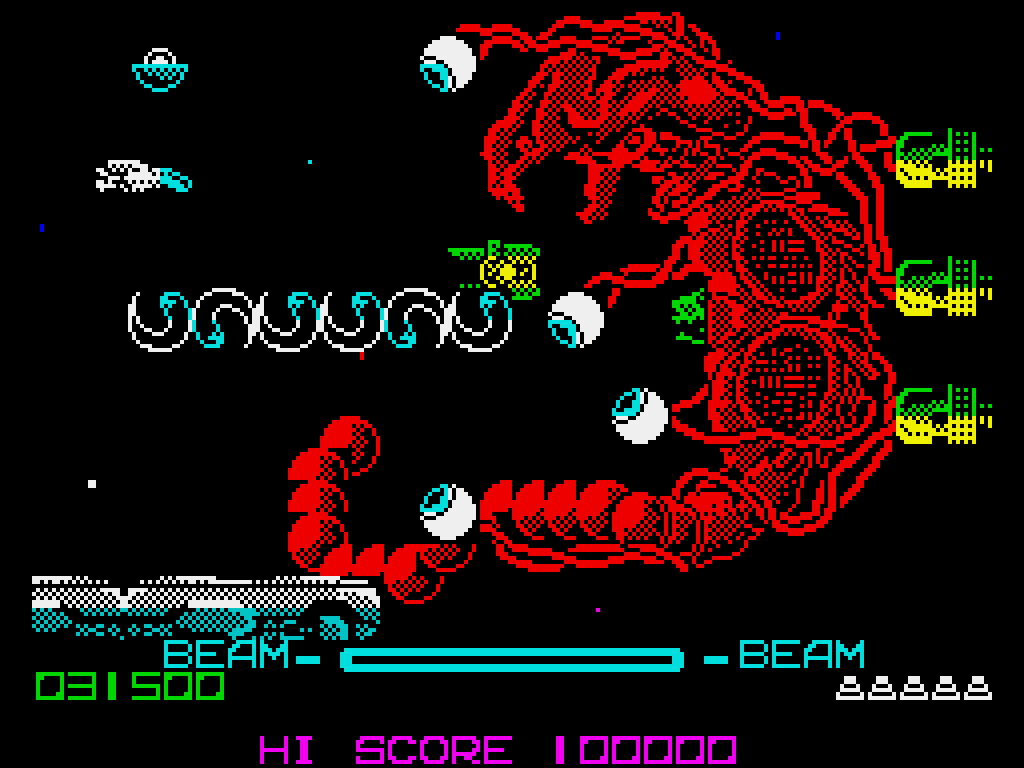

Other coin-op conversions were downright ingenious. In the late 80s, programmer Bob Pape famously took Irem’s spaceship shooter R-Type and somehow crammed it onto the ZX Spectrum’s meagre hardware; what’s more, the game was colourful, fast-moving, and actually looked recognisably like the arcade version. Critics in magazines of the era – Your Sinclair, Crash and so forth – were stunned at just how good Pape’s R-Type was. In fact, the port’s quality was so legendary among ZX Spectrum owners that, some 25 years later, Pape wrote a novella-length book about how he programmed it.

That book, It’s Behind You: The Making Of A Computer Game, also provides an insight into how difficult it was to actually port an arcade game in the 8-bit era. In most instances, programmers weren’t provided with source code or assets from the games they were asked to convert; instead, they’d have to do lo-fi things like record videos of an arcade machine running the game and figure out how the thing was programmed by simply watching it.

Some arcade conversions were also made cheaply and in a considerable hurry; before he programmed R-Type, Pape recalls pulling a three-day coding marathon to get a port of Atari’s coin-op, Rampage, ready in time for its Christmas release. “And if you’re wondering where the game testing, quality control, bug reports were during all this,” Pape wrote, “then there’s a simple answer: there weren’t any.”

All of this helps to explain why, for every hardware-straining work of genius like R-Type, there were several sore disappointments like Nemesis – the ZX Spectrum port of Konami’s genre-defining shooter, Gradius. What was particularly strange about Nemesis was that, ahead of its release in 1987, Sinclair User magazine gave the game a glowing five-star review, its write-up accompanied by some screenshots that looked remarkably close to the original arcade. Not only was the finished game a jerky, borderline unplayable mess, but its graphics looked nothing like the ones published in Sinclair User. (This led to a minor 8-bit conspiracy theory: that there were two versions of Nemesis, and that Konami mysteriously published the terrible one. To this day, that mystery remains unsolved, though veteran games journalist Stuart Campbell dissected the available evidence a few years ago.)

Iffy arcade ports may have been all over the place, but on the flipside, a truly faithful conversion could rapidly acquire legendary status. The PC Engine, a hit console in Japan that emerged in America as the TurboGrafx-16, was barely released in the UK; all the same, the system garnered a certain cache among some British gamers thanks to its port of R-Type (yes, that game again). In those pre-internet days, the word was that the PC Engine port of R-Type was, miraculously, arcade perfect; unlike the ZX Spectrum or Sega Master System, the console was powerful enough to run an identical facsimile of Irem’s shooter.

In reality, the claims were a little wide of the mark; the original release of PC Engine R-Type was sold on two separate cartridges because of its size, and unlike the arcade version, the screen had to scroll up and down a little to squeeze in all the graphics. Nevertheless, the aura surrounding R-Type is a sign of just how much interest there was in “perfect” home ports of popular arcade machines. Indeed, it was this kind of fascination that led some, more affluent gamers to drop huge sums of money on SNK’s hugely expensive (but admittedly brilliant) Neo Geo AES. With its then-extraordinary 16-bit graphics and arcade-style controller, it really was a coin-op for the home – assuming you could stomach spending £200 per game.

In the late 80s, the Sega Mega Drive (or Genesis) was a more affordable option. Before Sonic The Hedgehog came along and became the console’s mascot, Sega used one of its hit arcade games, Altered Beast, as a showcase for the 16-bit machine’s processing power. Because the original Altered Beast arcade game used similar hardware, the console version looked fairly close – to a casual eye, even identical – to the coin-op. That the graphics were so big, bold and colourful did much to disguise the lumpen, repetitive combat of the game itself, at least at the time.

Over on Sega’s rival, the Super Nintendo, it was the mighty Street Fighter II that, along with things like Super Mario World, helped make the console such a success. The arcade version of Street Fighter II was such a phenomenon, in fact, that it wasn’t uncommon for British gamers to spend eye-watering sums on importing a Japanese SNES and a copy of the conversion just so they could be the first to get their hands on it. (The Sega Mega Drive later got a port of Street Fighter II of its own, which, while not quite as good as the SNES version, was still pretty close to the arcade.)

Ultimately, Street Fighter II – and its bloodier rival, Mortal Kombat – would mark the beginning of the end of what we can only describe as the Much Anticipated Arcade Conversion. While ports of great arcade games would continue in the PlayStation and Xbox era and beyond, the process of conversion no longer sparked the same fascination that it did a decade or so earlier. Gaming as a whole began to move away from the design principles of the arcade – limited lives, quick-fix action – even as the popularity of arcade games themselves began to dwindle.

To modern eyes, the whole era of coin-op conversions might seem rather strange. Why would anybody drop their precious pocket money on a game that bore only a scant resemblance to an arcade machine they might have played once or twice on a seaside holiday? If anything those conversions were a testament to how much of an impact the original arcade games had on impressionable young minds.

The ZX Spectrum conversion of OutRun was, even back then, objectively terrible. But if you put on the soundtrack, half-closed your eyes and really, really used your imagination, then you were transported. You were no longer hunched over a keyboard in front of a portable television – you were in an arcade, driving a Ferrari Testerossa in one of the coolest driving games of all time.