Animal Crossing: The Legacy of Tom Nook

As we celebrate the release of Animal Crossing: New Horizons, we're reminded that there is no escaping gaming's greatest taxman, Tom Nook.

When I was young, I used to associate April with a rhyme about rain my grandfather would recite like the closing statement of a philosophical debate, the approaching end of the school year, and the one day a year in which people made you miserable. That last one is still true. The only difference is that day used to be April Fools’ Day and is now the 24-hour period commonly known as Tax Day.

I’m not alone. Most Americans associate April with the time of year the dang government reaches into their pockets and takes their hard-earned money while the president works to lower his score on the back nine at Mar-a-Lago. There’s something about the finality of Tax Day that haunts even the most fiscally responsible adults. It most likely has something to do with the classic image of the taxman.

Do a Google image search for “Tax Man” right now and let me know how many positive results you find. People may have accepted the inevitability of taxes long ago, but that acceptance has done little to ease the fear that the mythical tax man inspires.

Surprisingly, there are remarkably few fictional villains in gaming that draw inspiration from that caricature. Perhaps that’s because money is rarely a finite resource in video games. It certainly rarely feels as vital and hard to come by in games as it does in real life. Nobody has ever tossed and turned at night wondering how they’re going to pay their mechanic in Grand Theft Auto.

But there is one notable example of a terrifying villain modeled after the dreaded tax man. Ironically, he appears in a game all about escaping the horrors of the real world, the kind of game that we could all use right now.

If you’re unfamiliar with the Animal Crossing series, think of it as an even more cartoonish take on The Sims or a variation of the Stardew Valley/Harvest Moon formula. You wander around a quaint village making friends with the locals, doing a little fishing, and sprucing up the old homestead. Mostly, Animal Crossing is a game about nothing. It encourages you to develop a routine of monotonous tasks and then makes you feel guilty when you don’t complete them.

That must sound terribly dull, but the brilliance of Animal Crossing lies in its simplicity. Animal Crossing is the type of game you can lose yourself in because it organically encourages devotion but doesn’t demand it. It recreates that classic image of the simple life we see businessmen in movies pining for on the train ride into the city. Get up with the sun, wander the woods, chat with your friends, and savor the little things in life.

Few people went into Animal Crossing expecting to become addicted to it. Then again, most people aren’t fond of acknowledging how much they crave a routine in their own lives. Animal Crossing allows you to develop a routine motivated almost entirely by your own desires. It combines the comfort of familiarity with the thrill of adventure. You feel like you’re making genuine progress every time you get out of bed, living an idyllic life of your own design.

It’s all a lie, though. As much as you want to believe you’re working for yourself in Animal Crossing, it’s just not true. The dark forces of capitalism pull the strings in Animal Crossing‘s world and it often wears some fetching sweaters.

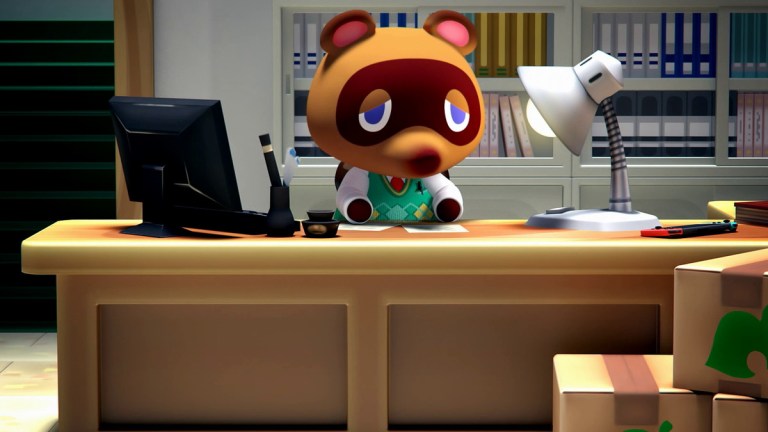

The moment you step off the train platform in 2001’s Animal Crossing, you are greeted by Tom Nook, who identifies himself as the town store owner and then immediately proceeds to mock you for being homeless. So far as neighborhood welcome wagons go, this little fellow ranks slightly below closed blinds, awkward stares, and hushed whispers.

But you see, Nook isn’t the welcome wagon, and he’s certainly not a simple shopkeep. He’s the town’s mafioso. He mocks you for not having a home because, in a few minutes, he’s going to make you an offer for a “cozy” slumlord special that you can’t refuse.

We mean that in the literal sense. You need to buy a home from Tom Nook in order to proceed with the rest of the game, and Tom is going to charge you a fee that you can’t afford. Never fear, however, as he has graciously agreed to a payment installment plan. You can even earn a little money by working in his shop. He knows you’re good for the cash even though he doesn’t really know you at all.

It’s a pretty ballsy business move. Then again, what would you expect from a character based on the mythical form of the Japanese Tanuki: a legendary raccoon dog classically portrayed as having an abnormally large scrotum.

The moment you enter into an agreement with Tom Nook, your life now belongs to him. You may fish, collect bugs, dig up hidden items, and interact with the villagers all you want and Tom will never hassle you. But eventually, you’re going to need to visit his monopolistic store. You’re going to want to upgrade your house. In those instances, you’ll need to fork your hard-earned cash – cheerfully referred to in Animal Crossing as “Bells” – over to Mr. Nook.

Oddly enough, Nook is at his most aggressive when you actually do pay him. Visit his store when you haven’t made a house payment in a while and he’ll “joke” about sending some of his cousins to meet you. Complete your payments to Tom and he’ll decide to automatically upgrade your house and impose a new – and much larger – debt on you.

Some people (including Animal Crossing director Aya Kyogoku) have argued that Tom Nook isn’t really a villain. After all, if you found a money lender in the real world who charged you 0% interest on a loan and allowed you as much time as you needed to pay your debt, you would likely volunteer to help them hide a body or spend the day Ikea shopping with them.

Despite Nintendo’s claims that Tom is misunderstood and the fact that the Animal Crossing team made him far less aggressive in subsequent games by changing his policies and altering his more threatening dialogue, it’s widely accepted that Tom Nook is Animal Crossing’s villain. The internet is riddled with fan art and videos which denounce Tom’s greed and shames the entrepreneurial raccoon for corrupting the simple life with his capitalist vision.

Nintendo can spin Tom Nook however it likes, but the truth is that Tom Nook is a villain. No matter how many bells you earn, you know that you’ll never be able to escape his boundless greed.

While it’s understandable that Nintendo would want to distance itself from the perception that the company intentionally implemented an evil tax man into a family-friendly game meant to inspire tranquility, the publisher’s denials ultimately only fuel the fire that Tom Nook would certainly charge you for if you needed it to stay warm in winter. Besides, in denying Tom’s villainous nature, Nintendo also denies Animal Crossing‘s creators the chance to take credit for having designed one of the greatest villains in video game history.

A great video game villain is more than just a maniacal laugh and an opposing view. A great video game villain affects the way we play the game. Psycho Mantis forced us to put our controllers on the floor and change controller ports in Metal Gear Solid. Goro challenged us to become better Mortal Kombat players in order to beat him. Great video game villains present a barrier between us and our goal that cannot be overcome by staying the course.

Tom Nook does this but in a subtle way. Rather than appear during the course of the player’s adventure and attempt to derail it, he lets them know right from the start that they are in his world. You’re working for your own happiness and the pleasure of the work itself, but you’re also working to fill Tom’s coffers.

We hate the taxman not just because he takes our money, but because he reminds us how much we value our money. We want the same thing as he does. Usually, such shared goals create a sense of empathy, but that is not the case in this relationship. Money has never seemed more real than when an invisible hand reaches into your pocket and takes yours.

The reason that people seem to harbor a special hatred for Tom Nook is that he makes us realize that we want things. If you weren’t in debt to Tom, how long would you really feel content digging for artifacts and catching fish? You want that bigger house. You want that NES in your home. You hate Tom because he stands in the way of simply getting these things. If he didn’t, you would sprint through the game’s progression system and wear yourself out in the process.

Perhaps we should learn to treat our own taxmen with a similar level of begrudging respect. Much like Tom Nook, they are villains we hate most because the evolution of our own desires gave birth to them. They’re easy to point to and say, “That’s the bad guy,” because doing so is a lot more satisfying than looking inward and coping with our overwhelming desire to consume.

Every story needs a villain, and for what’s left of my money at the end of tax season, there are few villains better than the taxman.