Fist of the North Star: A Trip Through the Surreal ’80s Anime

One of the most violent animated films of the '80s, Fist of the North Star is also one of the weirdest...

This article comes from Den of Geek UK.

British fans of Japanese culture had to get their anime fixes where they could find them in the early ’90s. The success of Akira prompted a trickle of Japanese animation, mostly via Manga Entertainment, but the selection was often leftfield to say the least. We got enjoyable fare like 3×3 Eyes, Project A-Ko, and Dominion: Tank Police in the first few years of the ’90s, but then we were also given Urotsukidoji: Legend of the Overfiend, a deeply strange slab of erotic horror pretty much guaranteed to generate controversy.

Indeed, much of the anime from that period appeared to be chosen almost at random, either based on what was already dubbed and readily available in the US, or what might appeal to an audience of 18 to 25 year-old males – presumably anime’s core market, given the kinds of movies and shows that emerged in the UK around 25 years ago.

Fist of the North Star was part of that first wave anime: a seethingly violent, feature-length action adventure seemingly hand-picked to delight young gorehounds and horrify tabloid newspapers. In retrospect, though, Fist of the North Star is more than just blood-soaked: it’s also incredibly strange in ways that weren’t necessarily apparent when viewed back in the 1990s.

First, a bit of context. In Japan, Fist of the North Star is known as Hokyuto no Ken, and began life as a highly popular comic in the early 1980s. Set a few years after a nuclear apocalypse turned the planet into a wasteland, the series follows a tall, muscular character named Kenshiro, the master of a startlingly powerful style of martial art called Divine Fist of the North Star. As society has fallen into a pre-feudal state where village sackings, robbery, and murder are constant occurrences, Kenshiro’s one of the few remaining forces for good in a landscape where the strong constantly pick on the weak. Through the various power struggles and talks about balance in the universe, most Fist of the North Star stories often boil down to Kenshiro beating his enemies in combat – vicious battles where heads and bodies explode in spectacular showers of gore.

The resulting TV series, directed by Toyoo Ashida and airing on Fuji Television, toned down the violence a fair bit for a broader audience, which is where the movie probably came in: released in 1986, when the original series was still being aired, the 110-minute feature was a kind of “Too hot for TV” version of the same material, with a level of excessive bloodshed and dismemberment that more closely resembled the manga. In the west, the level of violence evidently made some distributors nervous. Most releases, including the UK one, have odd filters to the most extreme moments, essentially hiding the gore, guts, and exploding heads behind an obfuscating haze.

Fist pf the North Star’s TV roots also explain why its animation is often a little crude by the standards of the time. It was created by the same director and personnel as the series, and effectively condenses dozens of episodes’ worth of plot into a single feature.

Most people who purchased or rented Fist of the North Star probably wouldn’t have been armed with all this background information, and so it’s a little difficult to imagine just how startling its violence once looked. The prologue alone is enough to tell the viewer that we’re far from the detailed cyberpunk of Akira: a series of idyllic landscapes, all blue skies, and green fields, gives way to a crimson hellscape of nuclear war and incinerated bodies. A few cuts later, and the planet has become an arid dustbowl where survivors vie over dwindling supplies of food, water, and fuel.

In the opening scene, Ken’s attacked and left for dead by his former best friend, who walks off into the shimmering desert with Ken’s now grieving girlfriend, Julia. Emerging months later in a hooded cloak and beard, Ken briefly turns into a mysterious wandering hero, like the Man with No Name from a Sergio Leone western. When vicious hoodlums attack villages or defenceless kids, like Bat and Lin, Ken will reliably turn up and punch the bad guys until they’re dog food.

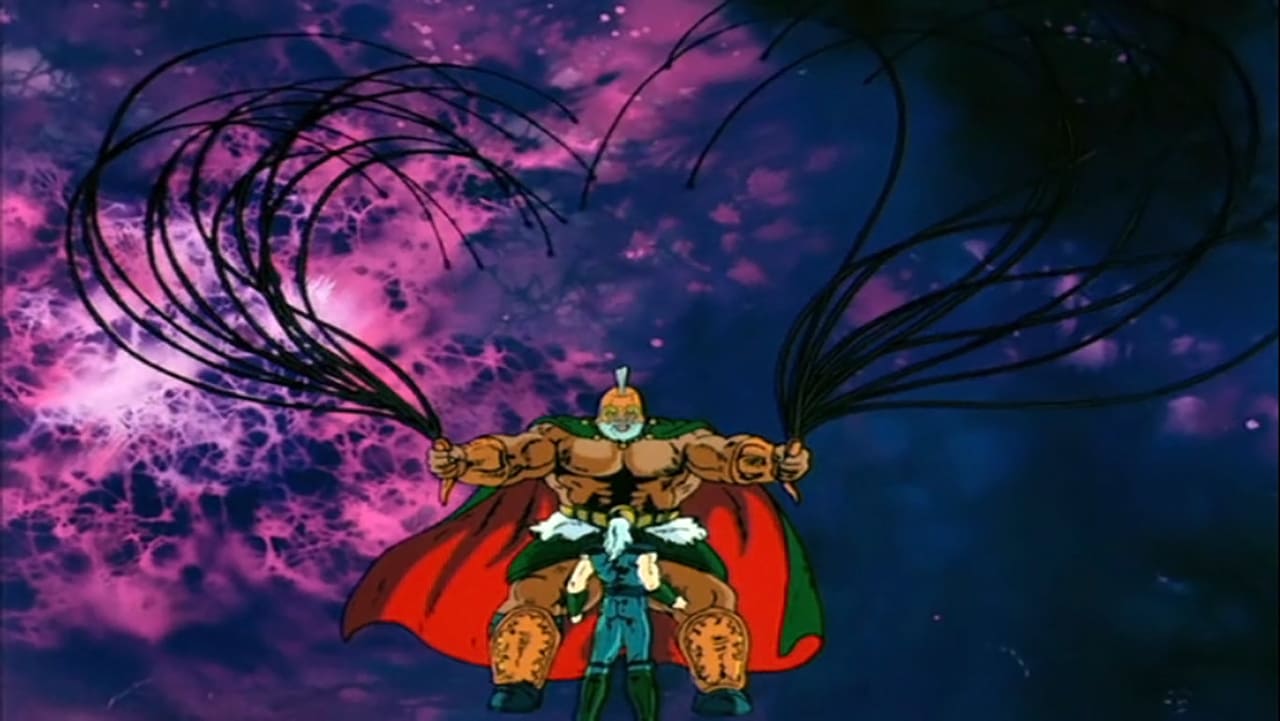

Anyone steeped in the anime and manga will likely accept Fist of the North Star‘s more curious trappings with a casual shrug. One of the side-effects of the atomic cataclysm, other than the deserts that stretch to the horizon, is that almost every guy on the planet aged between 18 and 40 has muscles like a professional wrestler. All this, despite the patent lack of gyms and protein shakes in this dismal post-apocalypse. Kenshiro himself looks like a cross between Bruce Lee and ’80s-era Sylvester Stallone, complete with muscular neck and hangdog expression. His enemies, meanwhile, are a freakish gallery of punks and long-haired sadists. Some appear to be merely above average height; others are so huge, like an obese body guard who Kenshiro kicks in the stomach at one point, that they can barely fit on the screen.

Fist of the North Star‘s influences are easy to spot, and read like a compendium of ’70s and 80s B-classics: the atmosphere of Sergio Leone spaghetti westerns are married to the postapocalyptic trappings of George Miller’s Mad Max movies, with a large helping of David Cronenberg’s Scanners thrown in for good measure. If anything, though, Fist of the North Star dials up the fetishism of Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior even further – society’s response to its collapse, it seems, is to immediately climb into an array of muscle shirts, vests, tight trousers, spiked shoulder pads, and Phantom of the Opera-style masks.

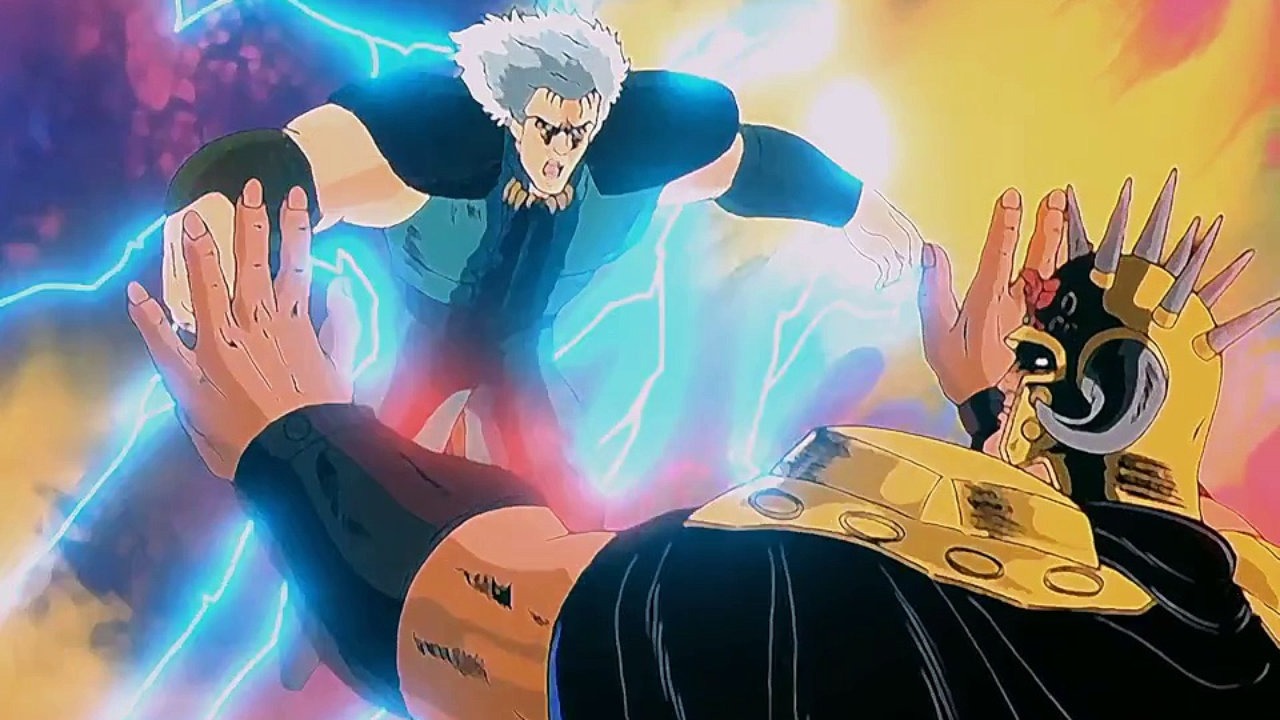

Director Toyoo Ashida brings a fetishistic quality to the action sequences, which are so full of slow motion and graphic detail that otherwise brief skirmishes stretch on for several minutes. Take Kenshiro’s first scene, which both establishes the cruel tone of the movie’s world and the hero’s central motivation: most revenge flicks get their betrayals over with pretty quickly. Fist of the North Star spends the better part of ten minutes detailing Kenshiro’s betrayal and torture at the hands of his supposed friend, Shin. As if all that bloodletting wasn’t enough, another opportunist (the hero’s own brother, Jagi) comes along and throws Kenshiro off a cliff. Then, just to be thorough, Jagi punches the top of the cliff, causing it to collapse on top of Kenshiro’s shattered body.

The essence of Fist of the North Star‘s philosophy can be found right here: never throw one punch when a flurry of 68 will do. Don’t just beat a character up, have them bashed about for ten minutes and then buried under several tons of rubble. The rest of the film essentially amounts to a series of vignettes, as Kenshiro moves from confrontation to confrontation with various villains – each with their own reason to fight our hero to the death.

The repetition and liberal use of slow motion conspire to give Fist of the North Star a glacial pace – not to mention an inflated runtime by anime standards: Ashida’s action banquet goes on for 110 decadent, orgiastic minutes. All the same, Ashida and his animators succeed in giving their postapocalyptic vision a sense of scale and, on several occasions, a trippy air that borders on the experimental. Baroque cities rise from the parched landscape; a blue, cannibalistic giant slices and eats its way through an army of black-clad ninjas, leaving a sea of bloodied corpses in its wake. It’s all heady, nightmarish stuff, like seeing the contents of someone’s diseased subconscious laid out in storybook form. That the western video release was accompanied by a borderline hilarious English dub only makes Fist of the North Star‘s weirdness feel all the more profound.

Ashida was no stranger to creating freaky, dreamlike worlds in the 1980s. He’d previously worked on Ulysses 31, a children’s animated series that mixed sci-fi with Greek mythology to singularly eerie effect. One year before Fist of the North Star, he also directed Vampire Hunter D, a post-apocalyptic horror-western that is, in most respects, a far more satisfying tale than Fist (fortunately, Manga Entertainment brought this film to VHS in Britain, too). All the same, Fist of the North Star‘s nihilistic, trippy quality is oddly fascinating if you can sit through it all. In this gloomy, seemingly doomed world, where Kenshiro’s entire family seems to want to kill him, the only ray of hope comes, somewhat comically, from a pink-haired kid and a bag of seeds.

As you may have gathered, Fist of the North Star isn’t exactly a masterpiece. Even the franchise’s more ardent fans would, we suspect, admit that it works better as an epic manga or anime. For westerners just beginning to learn about Japanese animation back in the 1990s, though, it was an unexpected glimpse into an alternate world. We’d only just hit the tip of the iceberg at that point, with Studio Ghibli’s wonderful output, and the startling breadth of TV and OVA animation, still relatively unknown to general audiences in the UK.

Better animated, better told, and more universal stories would later emerge on VHS and DVD in the west. Manga Entertainment would even go on to co-finance the classic Ghost in the Shell a few years after. Until then, Fist of the North Star filled a gap: overblown, grotesque, but quite unlike anything else available on video at the time.

The Geek’s Guide to SF Cinema: 30 Key Films that Revolutionised the Genre by Ryan Lambie (Robinson, 15th February, £12.99). Available in the UK from Amazon and The Book Depository, in Australia from Dymocks and Amazon, and in New Zealand from Mighty Ape.