Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell Review – Netflix Doc Unpacks Notorious B.I.G. Myth

Netflix documentary Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell keeps it real, to a point, cutting the Notorious B.I.G. Myth down to a life-sized story.

Biggie Smalls, born Christopher Wallace but AKA Notorious B.I.G., is a contradictory legend. A rapper who was always heard singing, a serious artist who never stopped clowning, he took the streets with him knowing it would take him down. His first album was called Ready to Die and his next was Life After Death, but he had a life in between. It is sad how his legacy is posthumous. But, as Sean Combs says at the very start of Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell, “This story doesn’t have to have a tragic ending.”

Combs, who co-produced the film, celebrates the contradictions and how they informed the music. When Biggie rapped he had “so much style I should be down with the Stylistics” he was being artistically autobiographical. Smalls had been singing those soul classics and listening to jazz greats from the earliest age. It’s what gave him the edge to win a legendary rap battle when he was just 17 years old. Combs says no one sounded like Biggie. He was unique. He remembers him as the “greatest rapper of all time.” Faith Evans recalls a force of nature who took everyone with him, so long as they would put in the work.

Musically, it’s disappointing that we get more talk about how great Biggie is over what makes his sound so unique. The most illuminating revelations come from jazz saxophonist Donald Harrison who recalls listening to bebop records with his neighbor, the young Chris Wallace. He explains how drummers like Max Roach incorporated syncopated rhythms which, if slowed down, are the pulsing root of Biggie’s delivery. They then expertly show how this works with a mix of Biggie rapping over a solo jazz drummer laying out a live bebop beat.

Biggie was known as a “gangsta rapper,” but he broke musical boundaries both on record and especially on stage. Biggie pulled in sonic impressions from the Geto Boys to Toto through Big Daddy Kane and into Kool G Rap. Wallace’s mother Voletta Wallace, talks about how the music of Jamaica figured strongly in Biggie’s musical development. His ears took in a wide range of music, he couldn’t even go to sleep unless country music was playing. That was one of the true revelations of the film. 50 Grand breaks down Biggie’s breakthrough “Party & Bullshit.” Easy Mo Bee talks about how “Juicy” developed. The film also talks with Junior M.A.F.I.A.’s Cease and Chico Del Vec. But the most obvious omission is Lil’ Kim.

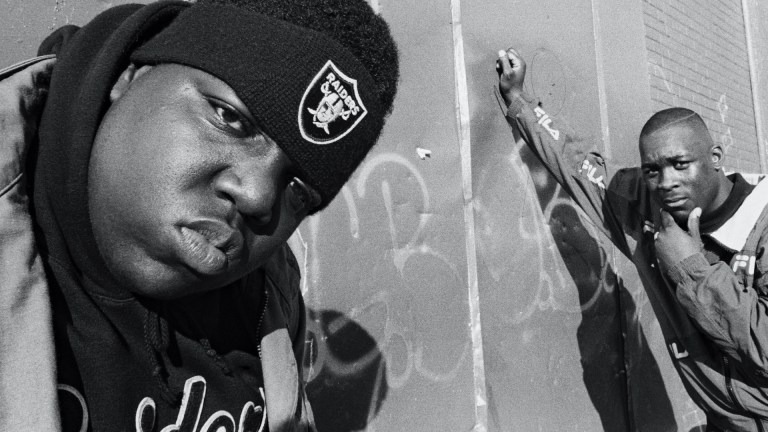

Nick Broomfield’s 2002 documentary Biggie & Tupac and the 2009 biopic Notorious both covered Biggie’s death. Emmett Malloy’s Netflix documentary doesn’t dwell on it. It opens at his funeral, where Brooklyn represented with a communal outpouring of love. Malloy is innovative in how he stages the interviews, setting one up in a huge abandoned church, others in theaters or the expanse of Jamaican exteriors.

The warmest recollections come from Voletta, who also contributed family photos capturing Biggie growing up in Bedford-Stuyvesant and vacationing annually in her hometown Trelawny, Jamaica. She didn’t even know there were bad words in his songs until her friend bought one of his records and told her. The film may be worth watching just for the look on her face when she remembers his album was “reeking with profanity.” She adheres to his warning that his music is not for anyone over 35, and never played it at home. Voletta is a country and western music fan, so she doesn’t let it keep her up nights.

This isn’t to say the documentary makes it look like Biggie hid things from his mom. One particularly amusing clip is him explaining how his mother has no idea what rappers do or how much they make. Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell isn’t anywhere near a warts-and-all exposé. Wallace was forever upfront. On his song “Suicidal Thoughts,” the Notorious B.I.G. rapped “When I die, fuck it, I wanna go to hell/Cause I’m a piece of shit, it ain’t hard to fucking tell.” There is nothing the documentary can reveal which Biggie didn’t proclaim for himself.

Songwriter Chris Wallace knew the cinematic value of his material and dealt it out like cinema verité. Combs notes Biggie was “always trying to put movies on wax.” Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell works as a gangsta picture. This is mainly because Biggie has such a ready-made soundtrack to it. He actually didn’t spend a lot of time as a drug dealer. It was a temporary job on the way to hip hop stardom. He just knew how to tell it better.

Biggie was always honest about street life, but Malloy lays out specifics on an animated map of the city, showing the boundaries of Washington Avenue to Grand Avenue in Brooklyn. And we get a short explanation about the difference between the Clinton Hill section, which was in the middle of a cultural renaissance, and Bed-Stuy, which included at least one entire street run exclusively by drug dealers every 10 blocks by urban decree. In the eighties, crime was a viable employment option and crack sales were an entryway to Benz territory, which Biggie reached by cornering the local market. The documentary spends too much time on his day job. He lived it. We get it. We want to know what he did with it.

Another highlight is the exclusive camcorder footage caught by Damian “D Roc” Butler, who shot Biggie on tour in 1995. He catches the musicians sweating on the buses, goofing around in hotel rooms, and smoking an unending rotation of blunts. But the best thing he captures is the audience reaction. Biggie wasn’t interested in watching himself on stage, he wanted to see what made the people move.

Biggie, we get from an interview, was shy. He doesn’t seem at ease in the spotlight of overnight success. The documentary does show his commitment to his community. He wanted to bring everyone he loved with him on the way up. Fans won’t be getting much new information, though it is heartening to see playful photos of the rap legend. Fans will enjoy the retelling of the legendary battle on Bedford Avenue, his rise through Bad Boy and the feud with Death Row.

Biggie will forever be linked to Tupac Shakur, whose name isn’t even mentioned until after the first hour of the documentary. Tupac and Biggie were friends and rivals. Notorious B.I.G. would have turned 49 years old this year. His murder is still an open wound. Malloy doesn’t present enough of the Biggie’s final two years. He could have shown why audiences connected so concretely with Ready to Die. How he made his mark on a generation.

We don’t learn much about Biggie we didn’t know before. The film manages to break past myth to show the man behind the words. But the documentary could have been rawer, more candid, more Biggie. Ultimately, Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell is an origin story, a coming-of-age film about a Catholic school kid in a uniform who hustled his way, almost, off the streets. It’s the chapter before the breakthrough.