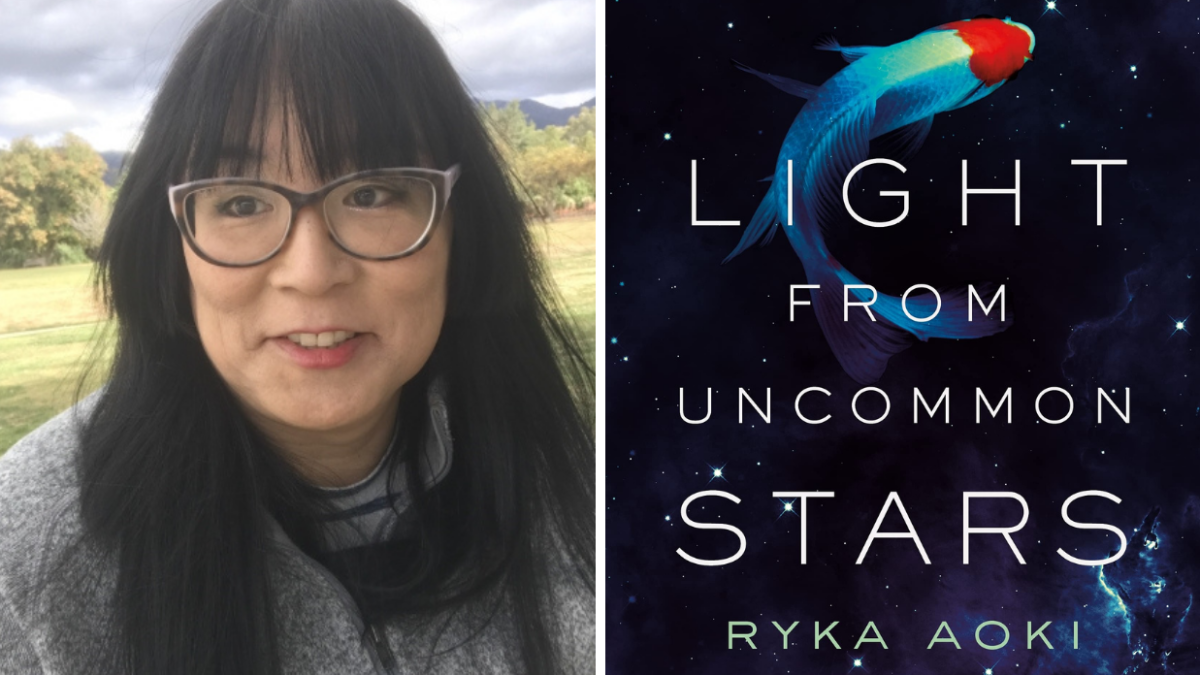

Donuts & Demons: Ryka Aoki’s Light from Uncommon Stars

"I respect both science fiction and fantasy, but I had honest intentions and reasons to mix them in Light from Uncommon Stars."

This feature is sponsored by

Shizuka Satomi, a violin teacher known as the Queen of Hell, owes one more soul to demons due to an infernal bargain she struck. Young violinist Katrina Nguyen needs to escape her homelife, where her transness is rejected by her family, and to start anew, hopefully making videos with her music. And Lan Tran and her crew are striving to build a stargate—before the Galactic Empire falls to the Endplauge—while selling donuts at Starrgate Donuts in Los Angeles. Light from Uncommon Stars is the story of how these three women’s lives intersect, and is a novel filled to the brim with music so beautifully described, readers can almost hear it in the narrative.

Katrina opens the novel with her flight and her passion for music; Shizuka comes in quickly after with her soul-contract deadline and her desire to find one last musician to condemn to hell. When readers first encounter Lan and her alien crew, they may wonder how author Ryka Aoki can pull off a story that is at once soul-bargaining-with-demons and refugee-aliens-building-a-stargate. But as the story progresses, the themes and characters dovetail together so beautifully that readers will wonder how they ever doubted.

Aoki explores what it means to be human, the nature of souls, and the importance of hope and love even in the face of what may seem hopeless, filling the novel with both good humor and acknowledgment of suffering. There is pain, and yet a sense that better things are to come. The love and care with which the characters imbue parts of their lives—whether it’s the music they play, the instruments they shape, or the food they create—gains a greater meaning by virtue of that love. The result is an incredibly powerful story of hope and redemption, of small voices shouting into dissonance and being heard. Ahead of the novel’s September 28th release, Den of Geek had the chance to pick Aoki’s brain about how this novel came together, and insights into her inspiration…

Den of Geek: First, what brought together the two very different speculative fiction tropes—soul-bargaining and stargates—together into the same story for you? How did you create a universe in your head where both things worked without contradicting each other?

Ryka Aoki: I respect both science fiction and fantasy, but I had honest intentions and reasons to mix them in Light from Uncommon Stars. I was a little bit worried about how people would accept this—or not. But I’ve been thrilled with how readers have embraced and accepted this book.

I think this book might resonate with readers because we all hold seeming contradictions. In the book, Shizuka Satomi mentions how great pieces of music contain such different-sounding sections and movements. And, as music reflects the soul, doesn’t that say something about us, and our own shifting arrays of motifs and counterpoints?

(Voiceover by Murdock Golder)

In my case, being of Japanese descent, and being queer, and being trans, means that I play a lot of different things to a lot of different worlds. Yet working toward true acceptance and love of self can be like composing your own sonata—you’re striving to express and share your entire music. The person who I am with my family lives in a different world than the person who teaches English and Critical Thinking. And that person seems very different from the writer, or the martial artist.

And yet, I don’t feel fragmented. I feel pretty whole.

And so, when I wrote Light from Uncommon Stars, I always had faith that it would work out, somehow—because I worked out, somehow.

(At least I’d like to think so…)

Demon Tremon Philippe and Shizuka’s relationship may bring to mind more of Mephistopheles and Faust than the devil at the crossroads. But there is a long tradition of musicians trading souls for greatness, brought into American folklore via blues musicians, who may have drawn on tales of Papa Legba rather than the European devil-bargaining stories. In the novel, you’ve brought many cultural traditions into play—where did you start from in the soul-selling elements? What did you borrow from earlier tales, and what did you invent whole cloth?

Thank you for asking this question because it lets me talk about another tradition. The early days of Internet message boards were the first time ever that trans people could speak freely yet relatively anonymously with people like them around the world. In fact, one of my dearest friends had such a board and they live in Iceland. We needed each other. We helped each other go through some horrible times… But there were also some goofy and fun times come as well—it was the first time that we realized that we’re all a bunch of science fiction and fantasy geeks. I mean, anywhere we can dream, right?

And I remember at the time being struck by how many trans women had created their own creation myths, to explain how their soul was placed in this other body. Many religions ignore trans people. Yet to know where one came from—and why—is a necessary question for many human beings.

In these stories, and the discussion surrounding them, there was much talk about having the soul of a woman, or the soul of a man if one were a trans man. “Do you have a female soul?” was a very relevant question to those with trans binary identities. (Discussions of nonbinary identities and gender fluidity were happening as well—entire vocabularies were being invented. Those were some exciting times.)

I think that even now many trans women, perhaps when first trying to make sense of who they are, still ask themselves this question.

And so, the cursed Shizuka Satomi, precisely because she is so focused on acquiring souls that she finds bodies irrelevant—offers Katrina the space and place to find her answers.

The descriptions and understanding of music and violins—and violin competitions—in the story are tangible. What is your music background?

I love writing music. I used to play in a band, and when I do my spoken word pieces, I compose all my own soundtracks. My main instrument is the piano, but I also play guitar, and some flute, and harmonica. For the most part, I am self-taught. However, I’ve been taking lessons for the past couple of years with a wonderful piano teacher—the irony is because I’m promoting this book, I’m on a brief hiatus from that.

However, I had no idea how to play the violin. I remember the first time I went into a violin shop. There were violins, but violins of different sizes, and cellos and violas and basses, and I was laughing to myself that I have no idea how to make music with any of this. I couldn’t put a tune together with one of these instruments to save my own life.

I did manage to teach myself some violin. And I really love the instrument. I have an acoustic violin from eBay, and I also have an electric violin now. This Christmas season, I am looking forward to jamming to some holiday music. We may never be ready for a committed relationship, but the violin and I have become good friends.

So, although I didn’t grow up in violin culture, as I researched violin culture, I found many parallels with a culture that I was familiar with—martial arts. Like many communities with overachieving children and parents with unrequited dreams, I found that in violin competitions, it was sometimes difficult to tell which was more important, the violin or the competition. This was so much like what I had seen as an annoying little martial arts kid. And so, those were the experiences upon which I drew.

The posturing, the pressure, the mind games…the nausea in the bathroom…so different, but not so different at all.

In addition to being a writer, you are a teacher. Are any of your own feelings about teaching reflected in Shizuka’s feelings about mentoring?

*giggle* ALL of them…the good, the bad, the obsessive, the self-serving, and the hopeful.

This novel felt, in many ways, like a pandemic novel–in a situation that should be full of hopelessness (the Endplague, a coming soul-deadline), there’s still this tonal quality, even in the early pages, that things will turn out right, even if we have no idea how that will happen. Was any part of the novel written during the pandemic? Do you see it differently now that it’s coming out as we’re still dealing with the coronavirus?

During the first few months of pandemic, most of the novel had already been written, and we were deep in edits. I was pushing so hard to get my story just right that the first part of the lockdown went by unnoticed. Plot hole here, inconsistency there…even without a lockdown, I don’t think I would have gone out, anyway.

These days, I’m feeling the pandemic more, especially because this is when I was to tour, sign books, and meet people in person. And, as I engage with the lockdown more actively, I do notice how the pandemic does seem to echo the themes of the Endplague. Although Covid-19 did not inspire the Endplague, I based the Endplague on how civilizations can often fall, not from outside cataclysms themselves, but from the conflicts and fissures they cause their populace…and a collective loss of hope.

In the book, without going into too many spoilers, Lan and her family come from a very advanced civilization that has conquered many diseases and social ills, but is still battling with divisions, suspicions, and fatalism.

Looking around at world today, the parallels are hard to escape.

Late in the novel, you use Bartók as a way of framing and understanding transness in a beautiful way. Could you talk about the theme of Katrina finding her voice through the violin, and about how music and self-intertwine in the novel?

Provided the instrument is well-maintained, when you play the piano, you’ll automatically play in tune. A violin can be perfectly in tune, but that is far from enough—you need to be in tune with yourself.

Furthermore, when I actually played the violin, I learned that certain notes resonate very well with other strings. In fact, sympathetic resonance is one way that a student can know if she’s in tune. If we listen for the resonances, we can feel the entire violin glow. There’s no better way to say it—it seems like the instrument glows.

This is very important to Katrina’s development, for human voices—and human souls—don’t have keys, or even frets, either. And when you’re playing in tune with yourself and others, you do get this internal glow. I think feeling this is very important to Katrina. It gives her security, weaves her into the songs of others.

But we are not always in harmony, nor should we be. Sometimes, our true songs are dissonant, or expressed in notes between notes. At that point, for all the rest of the world knows, your composition is wrong, or your intonation sucks. So, when your own music is so insistent, yet so at odds with what people expect—what do you do? Well, there goes Bartók.

There is a difference between playing with people in harmony and speaking to them in melody, after all. What does this mean for Katrina?

I think I’ll just leave it there.

Starrgate Donuts cannot fulfil online orders for their delicious donuts, unfortunately, as it is fictional, and videos of Shizuka Satomi’s performances are still not available to watch, due to interference from demonic forces, but Light from Uncommon Stars is available at bookstores everywhere on September 28, 2021. Find out more here.