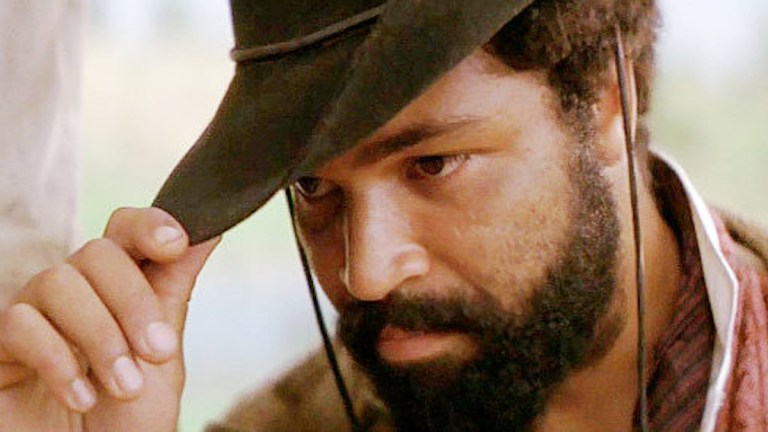

Jeffrey Wright Recalls His ‘Most Neglected’ Film (and Why the Studio Buried It)

Exclusive: Jeffrey Wright reminisces about Ang Lee’s Ride with the Devil, one of the best experiences of his career—and why the studio then swept it under the rug.

Sometimes it takes an outsider to diagnose a dysfunction in a family or the problem in a marriage. And when it comes to understanding the dynamics of the American Civil War, few filmmakers have captured the complexity and psychology that perpetuated this 19th century reckoning better than Taiwanese filmmaker Ang Lee. The director’s pensive and elegiac Ride with the Devil, adapted from Woe to Live On by Daniel Woodrell, gives a thoughtful and full portrait of the “border wars” fought between neighbors in Missouri. This includes the film’s tact of slowly but assuredly taking on the point of view of Jeffrey Wright’s Daniel Holt, a Black man who found himself riding with Missouri Bushwhackers, Confederate sympathizers who infamously raided the town of Lawrence, Kansas.

It’s a rich, layered, and even action-packed work, and yet there is a decent chance you’ve never heard of it, much less seen it. That strong probability remains one of the most frustrating memories in Jeffrey Wright’s career.

“I love that movie,” Wright says during a recent conversation about his latest project Highest 2 Lowest. “It’s like the neglected stepchild of my career in some ways, because I think it’s such a beautiful film and just grossly underappreciated. That had to do with the way it was released in that it kind of wasn’t released.”

Technically distributed into fewer than 65 theaters at the end of 1999, five years after Lee made a splash in the West’s prestige space via the masterful Jane Austen adaptation, Sense & Sensibility, and one year before he helmed an Oscar-winning blockbuster in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Ride with the Devil was an intentionally thorny film told from the vantage of both the losing side of the Civil War, as well as a Black man who actually rode with rebels like Tobey Maguire’s main character Jake Roedel, and enslavers like Simon Baker’s George Clyde. It is in fact Clyde’s childhood friendship with Holt that creates a fascinating space of clouded loyalties and (eventual) self-emancipation.

Of course the nuance of exploring this historical phenomenon is one of the central points of the movie, but according to Wright, it’s also the nuance that scared Universal Pictures’ new management after the studio was merged with PolyGram Filmed Entertainment.

“There was a changing of the guard at the studio from the time that we shot the film until the time it was finished,” Wright explains. “And the new gatekeepers didn’t quite understand the film. I think they were scared. They were afraid of it and not quite understanding how it was, for example, that a Black man would find himself fighting on the side of the Confederacy, history be damned. There was a guy named John [Noland], and he was a scout for Quantrill, who of course we show on his famous raid into Lawrence, Kansas. So despite the historical accuracy and also the ways in which Ang framed it, they just couldn’t quite get their heads around it.”

The picture is actually quite slippery in its shift of perspective. Initially told from the POV of Maguire’s Roedel, the son of a German immigrant who is both too poor to own a slave and perhaps too ignorant to think of a reason to fight in a war beyond all his boyhood friends are doing it, the film slowly watches Roedel’s self-awareness grow after spending a winter hunkered down in a makeshift bunker with Holt. However, it also becomes about Holt’s own self-actualization, particularly as he outlives the man who ostensibly gave him freedom, as well as his sense of debt to white men who would kill others over simple ideas—ideas like teaching abolition in a new schoolhouse. It even finds space to puncture the mythology around what was then the emerging Western outlaw, represented by Jonathan Rhys Meyers as not-Jesse James.

“For me what was exciting about that role was not that this was this freedman or soon-to-be-free man fighting for the Confederacy,” explains Wright. “For me what was interesting was that he was fighting for his own freedom and he was fighting to emancipate himself, as opposed to being emancipated by the Great White Northern Savior, which is what we very often see in cinema.”

He continues, “It’s one of my favorite experiences working on a film, and that had more to do [with us] riding horses every day for six months. It was just a joy. But it’s also a performance that I’m very proud of, and it’s one of the only films I think you’ll see in the entire canon in which a Black character rides off into the sunset at the end of a Civil War film.”

The movie indeed ends with Holt choosing to part ways with his friend on equal footing, and to also make sense of his own life as he rides off to discover what became of his family in Texas. The complexity of that ending also has echoes to this day, as many Americans continue to revise the realities of the Civil War, and perhaps a bit like some of the white characters in Ride with the Devil, shudder at their children being taught ideas in schools that make them uncomfortable.

Says Wright, “What I love too about the film is that it speaks to the messiness of American history and the messiness of American race relations. These things are not monolithic, and we are far more complex people than is most often written in the histories of who we are. I love that film.”