Sega Master System: The Most Underrated Console of the 80s

It ran a distant second to the NES, but the Sega Master System was an unsung great of the 8-bit era.

This article comes from Den of Geek UK.

When the Genesis began its global roll-out in Japan way back in 1988, it was the beginning of a new golden era for Sega, at least in the console market. Thanks to a strong marketing campaign and the immediate success of Sonic the Hedgehog, the 16-bit Mega Drive finally found success in America – which made the company, at least for a time, a viable competitor to its big rival, Nintendo.

It was a long, circuitous road up to that point. By 1988, Sega had already been in the console market for five years – not that many gamers in the U.S. took much notice. The firm’s first console, the SG-1000, was released on the same day as the NES in Japan and was one of several related systems that never made it out of its home territory.

It wasn’t until the Sega Mark III, later retitled the Master System for the NA and PAL markets, that Sega began to venture beyond its own shores. By 1986, Nintendo had already gained a valuable foothold in the American market, meaning the NES became the de facto console of choice for most kids in that country. In Japan, the Master System found itself fighting an equally difficult battle, with Sega having to compete with the evergreen NES on one side and NEC’s PC Engine on the other.

The Master System fared much better in territories like Europe and Brazil, and with worldwide sales topping out at around 13 million, according to IGN, the console was far from a complete failure. Compared to the monstrous success of the NES, though, was a drop in a bucket: Nintendo’s machine sold almost 20 million units in Japan alone. This, compared with the success of the Genesis (which shifted about 30 million units), meant that the Master System had long been overshadowed by both its competitors and Sega’s own ’90s legacy.

Despite its relatively small following, the Master System’s still a console with charm and a surprisingly huge library of games. Nintendo inevitably had the more iconic console titles of the ’80s – Zelda, Super Mario, Metroid, and so forth – but the Master System nevertheless has plenty of hugely playable titles of its own.

Super Mario‘s most obvious analog on the MS was Alex Kidd in Miracle World, and for a time, the lug-eared hero was Sega’s smiling mascot – at least until that pesky hedgehog rolled along. Not all the Alex Kidd games were classics (High-Tech World was a rebadged Japanese game that originally had nothing to do with the series; Shinobi World didn’t become an Alex Kidd title until late in development), but Miracle World and The Lost Stars are both fantastic platformers, packed with depth and weird design ideas.

Indeed, the Master System had plenty of great non-Mario platformers: Psycho Fox was rough-edged yet full of warmth, with its action panning out like a scatter-brained reworking of Super Mario Bros 2. Castle of Illusion, featuring an athletic Mickey Mouse, was an example of a game that was, for this writer at least, far better in its 8-bit incarnation than the bigger, louder 16-bit edition for the Sega Genesis. (In a pleasing reversal of the usual licensed game curse, just about all the Sega games based on Disney licenses were great – see also Land of Illusion and Donald Duck’s Lucky Dime Caper.)

As for RPGs and adventure games, the Master System lacked things like the NES’s Final Fantasy, but there were plenty of alternatives. Phantasy Star and Ys both got some classic entries on the MS; Ultima IV and Miracle Warriors were also worth checking out. As for action adventures along the lines of Zelda, Golvellius provided a colorful and quirky alternative, while Wonder Boy in Monster Land and Wonder Boy III: The Dragon’s Trap are arguably among the best side-scrolling action adventure games ever made.

The Master System couldn’t muster quite as many classic 2D shooters as the NES or PC Engine (Hudson, the creators of such classics as Star Soldier and GunHed, had those systems covered), but there was still a great selection to choose from. Power Strike, better known in Japan as Aleste, was a tough, top-down blaster as challenging and ingeniously designed as its rivals on other systems (its sequel is, unfortunately, so sought-after that we’ve never been able to afford a copy). Then there’s Fantasy Zone, featuring another early Sega mascot, the sentient ship Opa Opa. There was also a rock solid port of Irem’s arcade classic R-Type, and Sagaia, a port of Darius II programmed by Natsume.

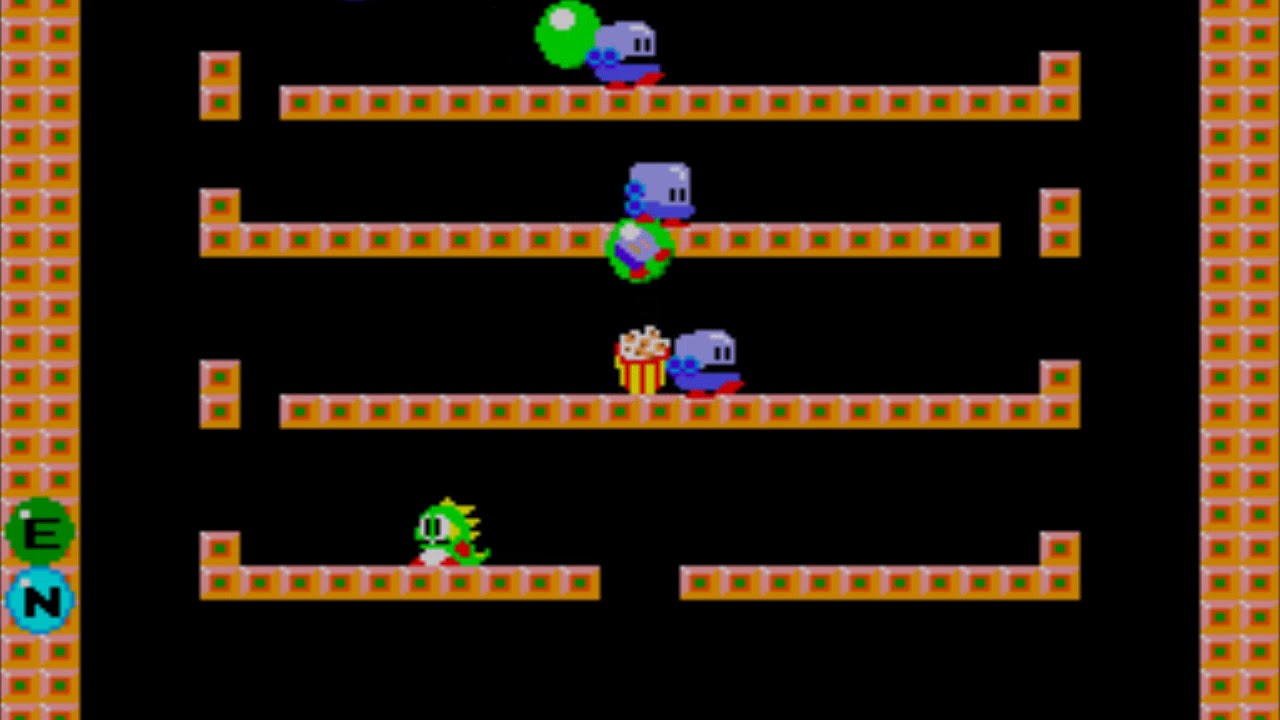

What was often overlooked at the time was that, in visual terms at least, the Master System was far more capable than the NES. To pick out one perfect illustration, we only have to compare a game that was released for both systems: a home edition of Taito’s classic Bubble Bobble. While the NES version is competent enough, its colors are more washed out than the Master System’s and the character sprites have an odd transparency issue when they cross over one another. The Master System version, on the other hand, is a true gem: not only is it closer to the arcade, but it also features 200 levels (versus the arcade’s 100 or so) and a couple of extra alternate endings and hidden stages.

Sadly, Bubble Bobble also illustrates one of the problems Sega faced in the late ’80s: Nintendo of America’s harsh licensing rules forbade third-party developers from making games for both the NES and rival consoles, meaning that the MS edition of Bubble Bobble was never released in the US. These rules were reined in by the early ’90s, but by then, the Master System’s opportunity to gain a foothold had long since passed.

We’ve got this far and we haven’t even mentioned the wealth of first-party Sega arcade games that graced the MS: Out Run, Space Harrier, After Burner, and many more besides. Ironically, time hasn’t necessarily been kind to these ports – if you have a burning nostalgia for those games, you’re probably better off playing them on the Genesis or the Saturn, which had the kind of processing grunt to carry them off more faithfully. Still, there are plenty of other Sega arcade conversions that still deserve a play 30 years later: the likes of Shinobi, Alien Syndrome, and Quartet are all simple yet rock-solid ports. The Sonic games, although originally conceived to show off the Genesis’ 16-bit “blast processing,” are also really good on the MS.

Even today, with the market for retro games and consoles exploding all over the place, the Master System is still remarkably friendly to collect for. The most common games can be picked up for only a few dollars, and there’s a plethora of ways to play them: through a modern clone console like the Retron 5 (with a converter), on a Genesis with a Power Base add-on, or on one of the various original Master System machines you can still pick up on eBay, from the swoopy original model to the more compact Master System II. Sure, boxed consoles and rarer games will set you back a fair bit (titles like Golden Axe Warrior, Power Strike II, and even the once-common Alex Kidd in Miracle World seem to be shooting up in price), but most games and peripherals are still pretty cheap. It’s a sign, perhaps, of how underappreciated the Master System is to this day, at least compared to its showier rivals.

Sega certainly didn’t do itself many favors when it came to marketing the MS in the ’80s. Those plain white boxes, criss-crossed with silver lines like graph paper and sparsely decorated with small hand-drawn illustrations, didn’t exactly shout from the shelves of your local video game shop. When the Master System came from Japan to the west, it mysteriously lost the FM chip that made its games so amazing – presumably, this was done to save costs, which is a crying shame, because a huge number of western MS releases still have FM soundtracks hidden in the cartridges.

Today, some of the Master System’s quirkier aspects now seem quite endearing. It was one of the few consoles to get its own 3D glasses – and believe it or not, they actually work quite well. The MS had its own lightgun, the Light Phaser, and a selection of pretty good gun games. Some early games came on dinky cards, like the media NEC introduced for the PC Engine, before Sega abruptly dropped them. If you include the Japanese Mark III as well, the Master System came in a bewildering array of shapes and sizes, including the strange-looking Super Compact, which only came out in Uruguay and Brazil.

In other words, the Master System had an entire history and catalog of revisions and peripherals that a great number of gamers are scarcely aware of. Dig a bit deeper, though, and you’ll discover an unassuming yet quietly brilliant console: robust, approachable, and packed with great games.