The Den Of Geek interview: Gerry Anderson

The grand-master of British sci-fi TV chats about getting shows made, turbulence in space and a Thunderbirds remake...

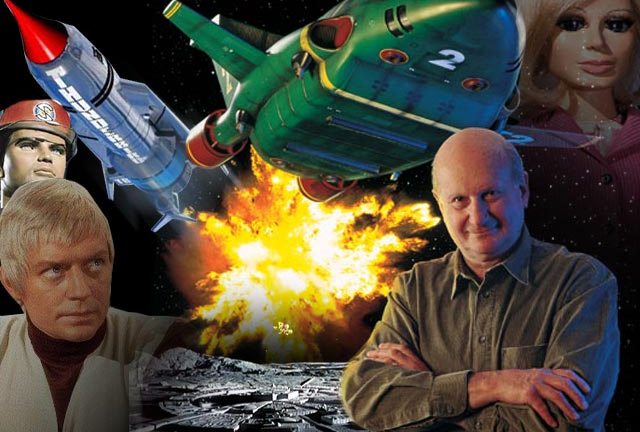

Many Americans still find it hard to believe that sci-fi TV producer Gerry Anderson is a Brit, so bold, colourful and high-concept were his US-oriented classic children’s’ shows such as Stingray, Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet and Joe 90. Anderson’s hugely successful puppet-based shows evolved in the late sixties into a new strand of live-action production which gave rise to new cult shows such as UFO and Space:1999, and also into a theatrical release, Journey To The Far Side Of The Sun (UK title: Doppelganger), where an astronaut on a deep space mission discovers the presence of a ‘mirror-image’ Earth permanently hidden from our view by its orbit. This cryptic sci-fi classic is soon to be released on DVD, and in honour of this, we were able to have a quick chat with the great man himself…

Am I right to believe that Journey To The Far Side Of The Sun predated UFO?

Errr….isn’t that terrible? I can’t remember [laughs]. Wait, no, I think it was around the same time. I left the puppet-film studio and went to Pinewood. No, thinking about it, UFO came first.

I mention it only because there are so many people from UFO in Journey…?

The answer to that is that for twelve years I used mainly the same crews on everything that we were doing, be they puppets or live-action. So very often I used to use the same artists. I had a lot of loyalty from people because I kind of rewarded people who did well by saying ‘Okay, you’re on the next one’.

You co-wrote Journey with your wife at the time – what led you to the idea of an opposing planet?

Well, when you say that I co-wrote the film with my wife at the time…I was very kind to her, because she used to take my dictation. If you study the story, the scientific content and the way the whole thing was a story of space-exploration, then yes – we co-authored it. But I would say I was the guiding light.

What influenced the increasingly dark tone of work like Journey and UFO?

I don’t think I ever really considered whether something was dark or not dark. Or comedy. I usually wrote the first script on every series that I did, or certainly played a very big part in that, and I just went where the hell the story sort of led me. Today people do great studies of audiences and what they like, and which films are successful and why. I never did any of that – I just used to want to write a good story.

In the case of Journey To The Far Side Of The Sun, I think the fact that it was originally called Doppelganger…that’s a German word which means ‘a copy of oneself’, and the legend goes that if you meet your doppelganger, it is the point of your death; following that legend, clearly, I had to steer the film so that I could end it illustrating the meaning of that word. But then of course, it went to America and they changed the title [laughs].

Were there any particular problems in making of such a logistically complex movie?

The film, I thought, was well-directed, but I did clash with Bob Parrish – the director – when it came to travelling in space: he started shooting the interior of these capsules flying like an aeroplane – you know, bumping along through cloud and banking when they turned and all this sort of thing. I went along and politely said ‘This is wrong, you’ll have to re-shoot it’. And that’s when world war three started, because I said that spacecraft won’t do that. He said ‘How do you know?’. But it’s easy to work out scientifically – they’re flying in a vacuum; there’s nothing to cause any movement. There’s no air. And he said ‘Well maybe that’s true, but the audience will not understand if the capsules are not moving like an aircraft. And so it went on.

So there was a certain amount of tension. But we had a wonderful cast and I got on very well with them.

You must have been very pleased to have been nominated for an academy award for the effects on the film…?

Oh yes, we were.

The opportunities that you gave to effects people like Nick Alder, Derek Meddings, Brian Johnson and Martin Bower took many of them off to Hollywood. How do you feel about having made such a huge contribution to the effects industry from Britain?

What happened, which I’m very proud of, is that these people started with me as very young people…Derek Meddings, for example, on my very first puppet films, used to come along to the studio after his work and paint all our backings for us, and then as we expanded we then took him on as a special-effects assistant. Then we started our own special-effects department. Then we ended up with a very big special-effects department! And then, of course, he went on to bigger and better things, which was great for him; but that meant to say that I had to find a replacement. I just used my judgement about people, and I guess I was always very lucky to find somebody that would very quickly become another Derek.

In the era of James Bond, did you ever feel you might be going too far to the American side of the market?

No, because we’re talking about the sixties, and at that time very very few British films or television series were shown in the states, and that was where all the money was. And so in order to get a big budget in the first place – which I always wanted to get – I had to, as far as possible, tailor it so that it would be suitable for the American market.

It wasn’t difficult, because most of the subjects I was making wouldn’t have been believable had I not made them American. For example, if I had said that the moon rockets were being launched from Scunthorpe, I don’t think that it would be very believable [laughs]. So it automatically fell into the category of an American film because that was what made sense at the time.

Having been actively involved with CGI through Captain Scarlet, what are your feelings on it as a technique, as opposed to puppets and live-action?

I think it’s horses for courses. I think it it’s an action picture, then of course it means that you can shoot with live artists and do all the special effects with CGI. The thing about CGI is that nothing is impossible – if you want to blow up the empire state building, no problem. If you want a man to dive from two hundred feet into the sea, no problem. It’s a tool, but I think it’s wonderful, and enhances the movies of today.

For me, it made great sense. I wanted to remake Captain Scarlet, and the puppets – although we tried so hard to make them look realistic – they had problems that we couldn’t overcome. But then with CGI…in our case we had over two hundred computers working – 200 seats, that is – and of course we were able to bring the puppets to life and get them to do whatever we wanted them to do. So, of course, for me it was wonderful.

You had a fantastic ally in many of your shows in the music of Barry Gray – do you think the art of the great title sequence and strong melodic score has been depreciated a bit since those days?

I guess the reason is that when, for example, I was making Thunderbirds, we scored our music rather than going to a library to get music and try and make it fit. We scored our music with Barry Gray writing it all, and it was recorded usually with 80-100 musicians. For a kids’ television show.

That was because then there were people around like Lew Grade who had the foresight to hear an idea and talk about it and say ‘Yes, I can see that being a hit – I’ll put up the money’. Today, of course, all that’s changed. You have accountants now and TV executives who want to have it proven that something is going to make a profit. That’s something that’s impossible to prove. And anyway, to prove it is to make it for thrupence, and think ‘Well it’s bound to make something at that price!’. This is it – the quality’s gone down and people’s creativity has been strangled.

So you’ve found an increasing lack of commitment from programme backers towards you over the last thirty or so years?

From the time that Lew Grade was deposed, yes, that’s so. That’s what happened to me. But I spent sixteen years with Lew Grade and I went from just one production to another to another, right the way through. But Lew passed away, unfortunately, some years ago, and it’s difficult. I mean, people like me are branded as independent producers, and it’s a silly title really, because independent we are not.

Were you ever tempted to get behind the director’s chair more often when the live action started to kick in at the time of Doppelganger and UFO?

Here again it was the big studio attitude that caused that. In the case of Doppelganger, the intention was expressed by Universal – and they put up the money – that they wouldn’t give us the go-ahead until we got an ‘A’-class director.

And so we were all in our offices, we had all the key people on board, and we waited for eleven long weeks until Bob Parrish, for some reason or other, left the production he was on. Then we saw him and we phoned Universal and said ‘We’ve got an A-class director’ and they said ‘Ok, go’. So you can see that’s an example of how people then, and particularly now, don’t like to take chances with emerging talent.

Can you tell us anything about your upcoming projects?

Well, I’ve said this a couple of times this morning, I hinted that I was negotiating for the rights that would enable me to remake Thunderbirds. And that seems to have spread like wildfire [laughs], so there’s no point in concealing it anymore. I am talking to Granada about it – they own Thunderbirds. What will happen, I don’t know. But I’m hoping and praying that they’ll agree to me buying it and enable me to make a new show.

Were you able to find any redeeming features in the Jonathan Frakes movie at a little distance from it?

I can’t think of one single thing about that film that I could remotely praise. It seemed to me that it was made by people who hadn’t got a clue what Thunderbirds was about and what made it tick. They chose to do an old Hollywood trick, by copying a huge success – Spy Kids. So the attitude is ‘It’s a huge success! Quick quick quick, make another one, and if it’s got to be called Thunderbirds, well that’s fine’. No, it was an unmitigated disaster. I was not involved – something I ask people to make quite clear for my friends out there…

We could tell you weren’t involved.

[laughs]

There’s been much talk over the years of rebooting other franchises of yours, such as Space:1999 and UFO; do you think these might come to pass?

I don’t know; all my properties, mainly because they were all made for Lew Grade, who I thought was the most wonderful person I’ve ever met; he bought my company and I trusted him with my life. I just expected Lew to go on and on and on and I would just continue making films for and with him. Unfortunately he was deposed, and then my house collapsed. And it’s a great shame because he was surely one of the best people we’ve ever had in this country that supported our business.

But I’ve heard rumours that they’re going to bring these properties out and remake them. I hope so.

So do we. Gerry Anderson, thank you very much!

Journey To The Far Side Of The Sun is released on DVD on the 8th of September.

Underappreciated TV: UFOSpace:1999 – the past is fantastic!The Gerry Anderson ready reckonerThunderbirds – the best title sequence ever…?