Black Mirror: How ‘The National Anthem’ Started It All

The Black Mirror series premiere set the satirical tone for what was to come, but was its shocking premise too much for some?

This article is part of our Black Mirror Rewind series. It contains heavy spoilers.

Black Mirror Season 1 Episode 1

When looking back at the first episode of Black Mirror, it’s easy to praise it for its prophetic take on politics in the era of social media. “The National Anthem” is often summarized as “the one where the prime minister has to have sex with a pig,” therefore prompting many viewers to focus on the fact that the show uncannily predicted the subsequent exposé about what David Cameron did with a pig during a college hazing ritual. However, this ignores the fact that the series premiere likely scared off potential viewers who thought that bestiality was only the start of a too-shocking-to-watch anthology series.

Perhaps the initial message needed to be strong to bring home the idea that Black Mirror would not simply be delivering the allegories of The Twilight Zone, to which it was inevitably compared; it was going to be pure, cutting satire about the role of technology in our lives, warts and all. British viewers likely knew what they were in for from creator Charlie Brooker, who worked on acerbic shows like Nathan Barley and Screenwipe, but the U.S. audience may have had trouble convincing themselves or others to tune into a show containing suggested pig sex in its premiere.

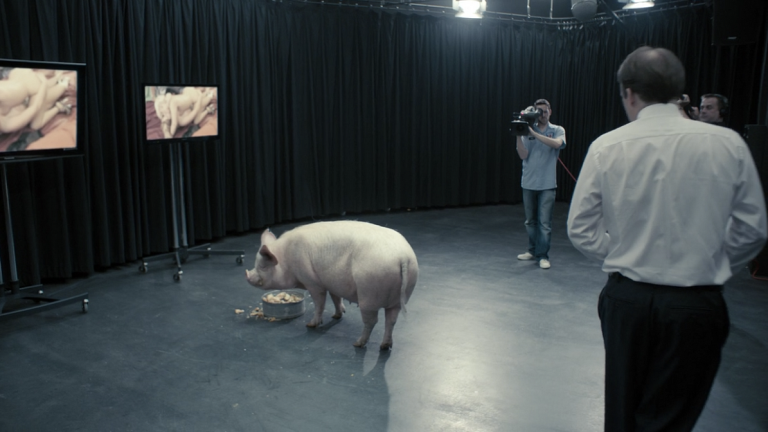

But the first “black mirror” had to be the one created by our computer monitors, reflecting our basest reactions to a public political scandal unfolding through video streams and on television. As the exposition began with a kidnapping of a member of the royal family, the demands of the perpetrators could have been as banal as the release of terrorist brethren or the withdrawal of troops, but the insistence that the prime minister have sex with a pig live on television titillated the public with its audacity, especially in conjunction with the celebrity of the princess, a critical element in swaying opinion.

As the PM’s advisors scramble to combat the threat, they find themselves beholden to the fickle nature of public opinion, which is instantly trackable in the Internet age via social networks. When the attempt is made to use green screen and special effects to assuage the kidnappers, the public is as outraged as the perpetrators that their elected officials would seek to deceive and equivocate on promises made. It’s not only a condemnation of empty rhetoric and slippery politicians but also a reflection of how quickly and decisively the Internet can be used as a weapon of attack.

As an introduction to the themes of Black Mirror, “The National Anthem” may have been risky, but as a representation of the series as a whole, it’s brilliant. Much is made of the horror and disgust of the prime minister himself, played by Rory Kinnear, and the barely restrained quiet of his staff, played by Lindsay Duncan and Donald Sumpter, but the public is focused on the suffering of the princess, whose finger is supposedly cut off in retaliation for the visual effects deception. Which camp are the viewers supposed to associate themselves with? That discomfort, although dangerously upstaged by the bestiality element, is key to audience understanding of what they’re in for in subsequent episodes.

That being said, there are moments of humor hidden in the background to draw viewers in. The visual effects artist, for example, refers to his previous work on a “moon-Western” called Sea of Tranquility, perhaps making an oblique reference to conspiracy theories surrounding the veracity of the 1969 moon landing. More overt comedy arises from the prime minister’s “stunt double,” as it were, who chats up the security detail and puts a green screen mask on, asking where his “co-star” is.

The payoff, and what makes this episode of Black Mirror an effective opener despite its off-putting premise, is in the montage of public reaction as the prime minister fulfills his coital obligations. Like the audience perhaps, the crowds of onlookers go quickly from smiling fascination to utter disgust, not just at the act being performed before them but at themselves for bringing it about, unable to look away. One hospital employee mutters, “Jesus, poor bastard,” but when another makes a move to change the channel, her co-workers stop her.

Then the clincher: we learn that the princess was released a half hour before the PM began his porcine rendezvous, the perpetrator dead by his own hand, having performed his masterpiece of social manipulation. And that’s when Black Mirror viewers realize along with the government official who ponders aloud, “That’s what this is all about: making a point.” The cover-up begins, and everyone moves on.

And perhaps that’s the message Brooker and company wanted to convey moving forward as Black Mirror viewers continued through the first season and beyond. “A statement will be made,” the series seemed to say, “and you will be disgusted, horrified, and amused all at the same time.” Four seasons later, it seems the mission was accomplished.