Why Elvis Should Have Listened to B.B. King

Elvis and B.B. King jammed into the night, but you might not call it rock and roll. You might also wonder if Presley learned the right lessons from his savvier contemporary.

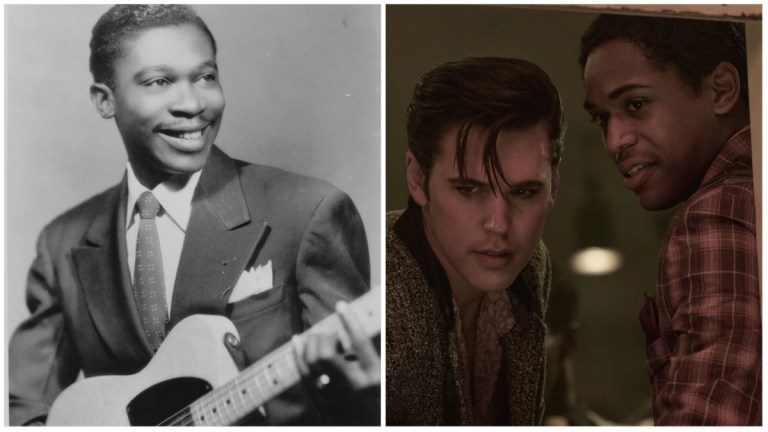

“You don’t do the business, the business will do you,” B.B. King (Kelvin Harrison Jr.) tells the rising Elvis Presley (Austin Butler) in Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis. He says this after a late-night jam session which includes Little Richard (Alton Mason), and while the blues guitarist is admiring the shiny new ride owned by the white rock and roll sensation. King advises Elvis to start his own label.

In reality, B.B. King did just that in 1956. At the time, he was coming off his best year, according to King of the Blues: The Rise and Reign of B.B. King, by Daniel de Visé. King had just packed the Howard Theater in Washington D.C. and Harlem’s Apollo, as well as 340 other venues. Born Riley B. King on a Mississippi plantation in 1925, B.B. “Blues Boy” King had risen to the height of his musical popularity by the mid-1950s.

And yet, his Orchestra’s singles were still being consigned to bargain bins by RPM Records. So King founded his own record label, Blues Boys Kingdom, and planted himself squarely in the center of the blues: Beale Street in Memphis, Tennessee. Elvis should’ve listened to the advice he was given, if at least in Luhrmann’ new film.

The Luhrmann biopic is told through the eyes of the man who bled Elvis dry, Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks), who sees the future “king of rock and roll” as a circus freak. But the film shows Presley as a man seeped in authentic musical roots. He grew up in a Black neighborhood in Tupelo, Mississippi, attended services by Rev. Herbert Brewster at the East Trigg Avenue Baptist Church when his family moved to Memphis, and did it for the sheer joy of gospel music, according to Pamela Clarke Keogh’s Elvis Presley: The Man. The Life. The Legend.

B.B. learned his first three chords from an electric guitar-playing minister at the Pentecostal Church of God in Christ before moving to Memphis and twisting the finger-stylings of Blind Lemon Jefferson and T-Bone Walker through the bent strings and vibrato of his own sound.

King and Presley both started their careers at an independent studio, run by the man with the keenest eye for talent in the city: Sam Phillips, the founder of Sun Records, which was on Beale Street. When B.B. first cut tracks at Sun Studio, he was playing nights with Bobby Bland, Johnny Ace, and Earl Forest in a group called the Beale Streeters.

Phillips captured the birth of the musical revolution, producing blues expressionists like King, Howlin’ Wolf, and James Cotton, as well as what has gone down in history as the first rock and roll record. Chicago’s Chess Records put it out, but “Rocket 88” was produced on Beale Street, by Phillips, in 1951, according to Peter Guralnick’s Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock ‘n’ Roll.

The single’s label was a misprint, the band is called Jackie Brenston and His Delta Cats but should have been credited as Ike Turner and his Kings of Rhythm featuring Jackie Brenston. Still, it was not a misstep. Not only is “Rocket 88” recognized as the first song to encapsulate the genre; it features the first rock and roll distortion guitar, played by Willie Kizart. He broke his amp on the way to the studio, stuffed it full of newspapers, and Phillips loved the sound. It was original, like a white kid who “sounded Black,” as per the new 2022 Presley biopic.

In his 1996 autobiography, Blues All Around Me, King defended Presely’s legacy from accusations of cultural appropriation. B.B. wrote, “Elvis didn’t steal any music from anyone. He just had his own interpretation of the music he’d grown up on, same is true for everyone. I think Elvis had integrity.” B.B. first met Elvis in Phillips’ studios, during the “Million Dollar Quartet” sessions with Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, and Johnny Cash.

“I saw all of them, but they didn’t have much to say,” B.B. recalled in King of the Blues. “It wasn’t anything personal, but I might feel a little chill between them and me. But Elvis was different. He was friendly. I remember Elvis distinctly because he was handsome and quiet and polite to a fault. In the early days, I heard him strictly as a country singer.”

But Elvis heard King. Even as he made his first television appearance on Louisiana Hayride, the rockabilly singer was catching rhythms and blues. During segregation, Presley was regularly seen at Black-only events, like the Memphis Fairgrounds amusement park’s “colored night,” or Black radio station WDIA’s Goodwill Revue charity event featuring King, Ray Charles, the Moonglows, and comedian Rufus Thomas.

“What most people don’t know is that this boy is serious about what he’s doing,” King remembered in King of the Blues. “He’s carried away by it. When I was in Memphis with my band, he used to stand in the wings and watch us perform.”

But only watch. Phillips sold Elvis’ contract to RCA Victor, where “Heartbreak Hotel” hit number 3 on the Black charts. The Platters’ “The Great Pretender” hit number 1 on the white pop charts in February 1956. Presley’s cover of Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog” topped both Black and white charts on Sept. 5 of that year. While a top-seller like Nat King Cole was assaulted by white audiences at the time, Presley crossed over. But record contracts being what they are, he couldn’t always perform where he wanted.

In the film, while telling Presley about his own record label, King says he can play where he wants, when he wants, and if an audience doesn’t like him, he can plug in somewhere else. On Dec. 7, 1956, King brought his guitar leads to the amps at the Ellis Auditorium, where he was co-headlining WDIA’s annual benefit concert with Ray Charles. Elvis took them up on their invitation, but could not perform because of his contract with RCA. Rufus Thomas closed the show by leading Elvis to the stage, but one hip-swivel too many brought an adoring audience rushing in and the police had to pry them off.

After the show, Elvis treated B.B. “like royalty” as they posed for pictures. “I believe he was showing his roots,” King said in King of the Blues. “And he seemed proud of those roots.” Some blues run much deeper than others, like Presley’s black hair was blond at the scalp.

“Elvis was doing Big Boy Crudup’s tunes, and they were calling that rock and roll [and] I thought it was a way of saying, ‘He’s not black,’” King would say later in his career.

The co-headliner of the Goodwill Revue event sang a similar tune.

“To say that Elvis was so great and so outstanding, like he’s the king, the king of what? I know too many artists that are far greater,” Ray Charles told Bob Costas on a 1994 edition of NBC news program Now. “He was doing our kind of music. So what the hell am I supposed to get so excited about?”

In the Luhrmann biopic, Butler’s Presley marvels at Little Richard’s stage presence while Harrison’s King points out Elvis would make more money recording the song “Tutti Frutti” than the piano stomping showman who wrote it ever could.

“If Elvis had been Black, he wouldn’t have been as big as he was,” Richard said in a 1990 interview with Rolling Stone. “If I was white, do you know how huge I’d be? If I was white, I’d be able to sit on top of the White House! A lot of things they would do for Elvis and Pat Boone, they wouldn’t do for me.”

In JET magazine’s 1957 investigative feature, “The Truth About That Elvis Presley Rumor: ‘The Pelvis’ Gives His Views,’” which cleared the singer of allegedly making racially prejudiced remarks, writer Louie Robinson also concluded Presley was making more money singing rhythm and blues than Black performers. The article quotes “Don’t Be Cruel” and “All Shook Up” songwriter Otis Blackwell who said “I got a good deal. I made money. I’m happy.” But Big Mama Thornton (Shonka Dukureh in the film) never caught her rabbit.

Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller wrote the 1953 track “Hound Dog” specifically for Thornton.

“I got one check for $500 and never saw another,” the versatile song stylist famously said. She called the song “the record I made Elvis Presley rich on,” at the 1969 Newport Folk Festival, according to Michael Spörke’s Big Mama Thornton: The Life and Music. When a drummer leaned into the more recognized beat at another concert, Thornton stopped mid-song. “This ain’t no Elvis Presley song, son,” she said, before taking to the set herself, and showing how it’s done. This was apparently rehearsed, with Thornton doing this at multiple shows as a way to explicitly reclaim ownership over the music.

Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis tries to teach a lesson by showing how even the King of Rock and Roll could be defrocked by a carnie-huckster. And it seems old hound dogs learn new tricks the hard day, even when a pal like B.B. King was offering a free course in the music business.

Elvis is in theaters now.