The Enduring Legacy of The Fly

The Fly remains one of sci-fi’s strangest and most iconic franchises.

The Fly — the 1958 version or the 1986 remake, take your pick — stands as one of the most memorable sci-fi/horror hybrids of its time. So it’s not surprising that Scream Factory recently released one of its now-standard deluxe boxed Blu-ray sets, containing all five films in the series and a truckload of special features, some ported over from the films’ separate DVD releases and others brand new.

What’s that, you say? All five films? Correct. For most people, the title The Fly brings up two iconic images: either David (Al) Hedison with a giant fly’s head on his shoulders or Jeff Goldblum in heavy prosthetics as he mutates into the monstrous amalgam known in the 1986 film as Brundlefly. Casual viewers may not be aware that the original film spawned two sequels, while the remake led to a follow-up of its own. All the sequels have interesting aspects to them, although none match up to their predecessors.

The Fly (1958)

A faithful adaptation of a 1957 short story by French writer George Langelaan that was published in Playboy, the original The Fly was released by 20th Century Fox and stars Hedison as Andre Delambre, a scientist whose experiments with teleportation turn horrific when he transports himself from one experimental chamber to another, unaware that a fly is trapped with him. What happens then is the stuff of sci-fi legend: Delambre’s atoms are fused with that of the insect, so that Delambre emerges with the fly’s head and front limb, while the tiny creature ends up with Delambre’s head and arm.

Yes, the science is wonky as hell: as many have famously pointed out, how does Andre’s brain stay inside the fly’s head so that he can communicate with his wife via written messages? And if his brain is in the fly’s head, how is it also in his own shrunken noggin as we can ascertain clearly in the film’s classic “help me!” ending? As with any good piece of storytelling — and both the original story and the film, directed by Kurt Neumann, are just that — the science gets papered over by the macabre, bizarre nature of the premise itself and the absorbing narrative.

Neumann and screenwriter James Clavell (who went on to write hugely successful novels like Tai-Pan and Shogun) wisely structure The Fly as a mystery. It’s told in flashback by Andre’s wife Helene (Patricia Owens), who as the film opens is under arrest for crushing her husband in a hydraulic press. While Andre’s brother Francois (a restrained Vincent Price) and Inspector Charas (Herbert Marshall) struggle to understand why a tight-lipped Helene killed her husband in such grisly fashion, the seemingly insane woman has her son and entire household searching for a fly with odd white markings.

Eventually Helene tells the story of Andre’s experiments, first with inorganic and then living things. In one eerie sequence, he transports the family cat but it fails to reappear in the receiving chamber — only its ghostly cries can be heard in the lab (again, it’s wonky science since the cat is supposedly disintegrated, but it works on screen). Andre is not the typical mad scientist: he does love his family even if he is a workaholic, and he truly believes his invention will help humankind.

But once he goes through himself, and the fly’s own base survival instincts begin to supersede his rational mind, the outcome is inevitable (even the proposed idea of resending Andre and the fly through the chamber seems ill-advised — what makes him think they would be reassembled into their separate selves and not combined even further?)

Its shaky science and now dated effects aside — although the first, late-in-the-film sight of Andre with the fly’s head on his body is akin in its shock value to the unmasking of the Phantom of the Opera in the 1925 silent classic — The Fly remains absorbing and entertaining, and it’s easy to see why such a mind-bending story could become one of 1958’s biggest box office hits. Although its theme of “there are some things that man should leave alone” was well-worn even back then, The Fly humanizes the story more successfully than many other sci-fi films of the time.

Return of the Fly

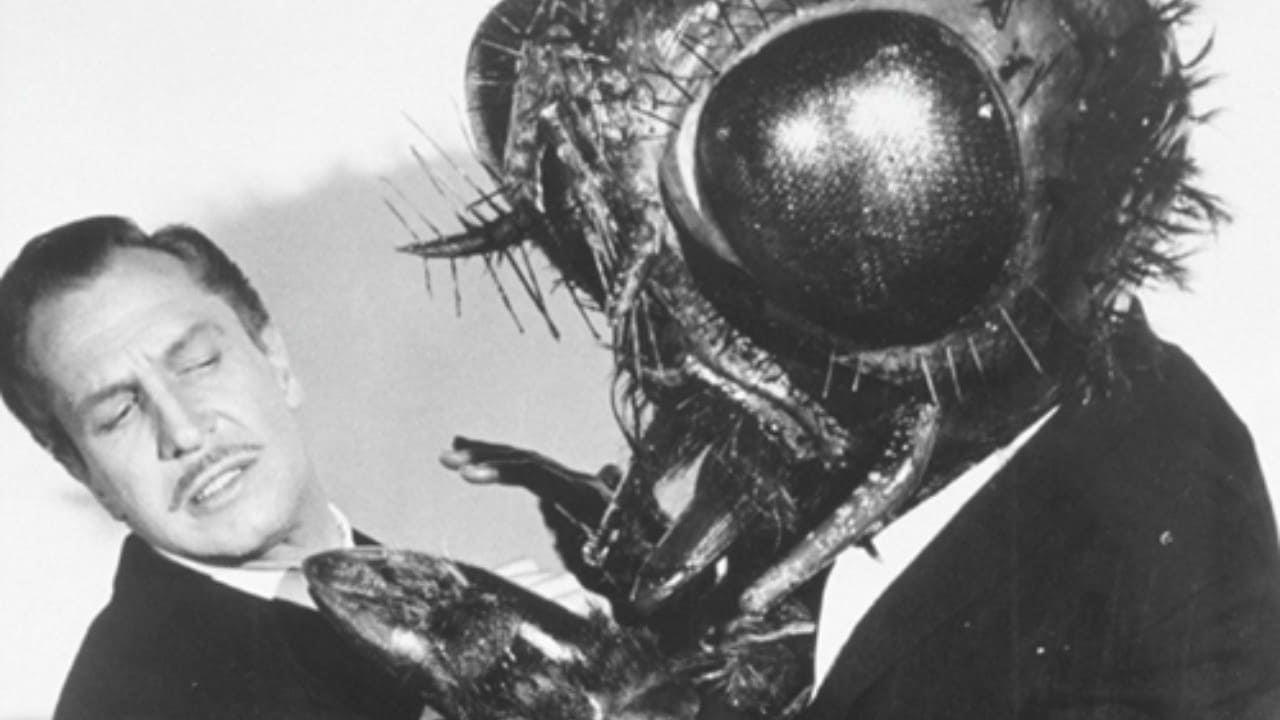

Strangely, the familiar image of a much larger fly’s head atop a human torso comes not from the original film, but its quickly dispatched sequel, 1959’s Return of the Fly. Anticipating the sequel to the Cronenberg film by 30 years, Return of the Fly features Vincent Price as the only cast member from the first film to reprise his role. This time he must contend with Andre’s now-grown son Phillipe (Brett Halsey), who wants to vindicate his father’s work by successfully completing his teleportation device.

The film’s villain is an industrial spy who wants to sell the Delambre teleportation secrets, and it is he who rather maliciously ends up throwing Phillipe into a disintegration chamber with a fly purposely trapped inside as well. At least that’s a nominally better solution than having Phillipe repeat his father’s mistake. Return of the Fly has its moments but is a rather typically pedestrian B-movie, made at a time when sequels were seen as quick cash-ins and not elaborate franchise expansions. Unlike the first film, which was shot in rich Deluxe color to give a high-class gloss, Return of the Fly is done on a budget and shot in black and white, which only adds to the film’s diminished feel.

Curse of the Fly

It was six years before a second sequel was commissioned and the result, 1965’s Curse of the Fly, was a strange addition indeed. Shot in England, the film for one thing messes with the continuity of its two predecessors: Phillipe Delambre has somehow become Henri Delambre, played as an older man by Brian Donlevy (The Quatermass Xperiment), who has successfully achieved teleportation with the help of his own son Martin (George Baker). Of course, there are a few mutated humans that father and son keep hidden on their property as a result of failed teleportations, including Martin’s first wife, and Martin himself has “fly genes” from the family history that require a special serum to keep them in check.

Directed by Don Sharp, Curse of the Fly is also shot in black and white and opens with a striking nighttime sequence in which an underwear-clad woman escapes from an asylum. That woman is Patricia (Carole Gray), whom Martin rescues on the road and marries shortly thereafter. Everyone in the film, from Henri to Martin to Patricia, is damaged somehow by their past, and as the title suggests, Curse of the Fly is more about that legacy than literal monsters — and although there are some of the latter in the film, there are no human/fly hybrids present.

Curse of the Fly raises a number of interesting ideas but leaves them ultimately unfulfilled. The low budget and lack of an actual fly monster probably dashed its chances, and the film was a box office dud that relegated the series back into the Fox vaults for the next two-plus decades (Curse of the Fly itself was rarely seen for years thereafter, and never received a proper home video release until a DVD set of the original trilogy was issued in 2007).

Producer Kip Ohman first had the idea of remaking The Fly in the early 1980s, recruiting screenwriter Charles Edward Pogue to write the script. But Fox was unhappy with Pogue’s work and declined to move forward. Ohman eventually convinced the studio to distribute the film if he could get outside financing for it, which he secured through producers Stuart Cornfeld and, improbably, comedy legend Mel Brooks.

The Fly (1986)

David Cronenberg (Scanners) was the first choice to direct, but since he was developing Total Recall at the time, a British filmmaker named Robert Bierman was hired. But then Bierman’s daughter was killed in a tragic accident and he withdrew from the project. At the same time, Cronenberg exited Total Recall and was able to come aboard The Fly, heavily revising Pogue’s script before shooting began.

The Fly arguably remains Cronenberg’s masterpiece, a somber meditation on disease and aging, not to mention a tragic love story and one of the most effective horror/sci-fi films of its time. Cronenberg’s version centers on introverted, eccentric scientist Seth Brundle (Goldblum), who is developing a teleportation device. His efforts are documented by a reporter named Veronica Quaife (Geena Davis), with whom he begins a romantic relationship.

Getting drunk one night after wrongly suspecting that Veronica is continuing an affair with her editor, he sends himself and that damn fly through the machine. But Cronenberg discards the familiar image of the man’s body with the fly’s head on top: over the next few weeks, as the fly’s DNA assumes control of his body, Brundle begins to mutate into a monstrous, increasingly unstable hybrid of a human and an insect: “I’m an insect who dreamt he was a man and loved it. But now the insect is awake.”

Somewhat typically, the studio resisted Goldblum at first and did not see him as a leading man. But his quirky style made him the perfect Brundle, and he was able to powerfully emote the scientist’s downfall into insanity and psychological turmoil even through pounds of prosthetics (which took up to five hours to apply). Davis had only had small parts in three previous films and The Fly provided her with her breakout role, despite actresses like Jennifer Jason Leigh and Laura Dern also being considered.

The Fly II

The Fly ends with a pregnant Veronica putting what is left of her lover out of his misery and leaving the fate of their unborn child ambiguous — that is, until The Fly II emerged in 1989 from makeup effects artist turned director Chris Walas. The latter was handed the big chair after he won an Oscar for his effects work on The Fly. Eric Stoltz starred as Brundle and Veronica’s child, who unfortunately carries his father’s twisted DNA.

Stoltz’s Martin — whose mother (not played by Davis) dies in an early childbirth sequence — is kept hidden away by Bartok, the sinister corporation that funded his father’s experiments. Aging rapidly and gaining both strength and intelligence through his unusual genes, Martin has the physique and mind of a 25-year-old by the time he is five — and is “hired” by Bartok to solve the mystery of his father’s telepods and make them work successfully. Martin also befriends and beds a Bartok employee named Beth (Daphne Zuniga) and it’s suggested that his transition to adulthood fully activates his fly genes, beginning a mutation that he may not be able to stop.

The film was not as warmly received as its predecessor (which was an enormous hit with both critics and moviegoers) although this writer has a soft spot for it and some fans appreciate the more traditional monster movie aspects of the picture. Many critics derided it for emphasizing gore and effects over story and character. But that’s not exactly the case, and The Fly II does have its tragic aspects that work better than reviews at the time might have indicated.

The original The Fly, Cronenberg’s film and The Fly II have all appeared on Blu-ray previously, but Curse of the Fly makes its format debut in the Scream Factory collection — which should now probably be considered the definitive home video archive of this series. The set compiles all the special features from the 20th anniversary DVD editions of the 1986 film and its sequel, including commentaries from Cronenberg and others, documentaries on their making and more, while new interviews and commentaries have also been included. Basically, if you’re a fan, this is the one package you’ll need — unless another sequel or remake, proposed on and off since 2003, finally gets the green light.

What makes The Fly Collection so enticing is that none of the five films is without interest. Clearly Cronenberg’s entry is the standout and a genre milestone, but the original is a classic in its own right and all three sequels have their compelling aspects. The teleportation element of the series, and what that means for humankind, remains ripe for exploration (Cronenberg at one point even wrote a never-produced sequel that would have taken a deep dive into this subject) and as with great or at least intriguing sci-fi, the metaphors can go on forever — even if the films themselves stop here.