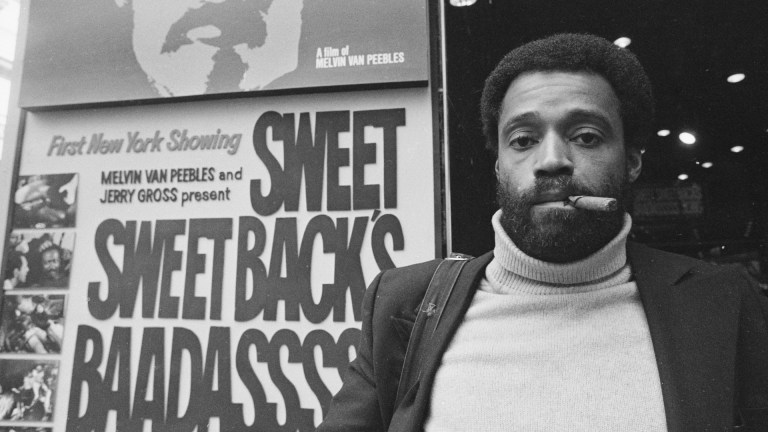

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song Was Revolutionary on Every Level

Melvin Van Peebles’s Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song sparked Blaxploitation Cinema but revolutionized underground film.

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, which turns 50 this month, is the opposite of the definition imposed on it. The 1971 film inspired the Blaxploitation genre, but Melvin Van Peebles exploited no one but himself. He got the money together, wrote the script and the music, selected the shots, aimed the camera, and starred in the film. He even did the stunts and post-production editing. Everything that came after was a reaction to his revolution. The father of Black cinema is one of the godfathers of independent filmmaking, and he turned everything upside down doing it.

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song defies all expectations. Unapologetically Black, it flips every stereotype back on itself. It reconstructs the constrictions of sexual identification. It wasn’t made for the institution. It was made for the people. “This film is dedicated to all the Brothers and Sisters who had enough of the Man,” reads the opening titles. That included the ones in suits at Hollywood studios. Even after the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Fred Hampton, the only African Americans people saw on the big screen were subservient to whites, or played by Sidney Poitier.

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song was released a few months before Shaft. According to Howard Hughes’ 2006 book Crime Wave: The Filmgoers’ Guide to Great Crime Movies, Ernest Tidyman originally wrote the character of John Shaft as white, but director Gordon Parks cast Richard Roundtree in the role. According to legend, it was because of Sweet Sweetback. Because the two films were released the same year, they share categories, but not aesthetics.

“What does a dead man need bread for?”

Shaft was co-produced and distributed by MGM, a major studio. Van Peebles shot Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song in 19 days on a budget of $500,000, and had to personally ask Bill Cosby for a $50,000 loan to finish it. He worked on a sporadic shooting schedule, and had to rethink the film as it progressed because of the shrinking funds. After the success of his racially charged comedy The Watermelon Man (1970), Columbia Pictures offered Van Peebles a three-picture deal. The studio wanted more comedies, but the director had something far more hysterical in mind.

The story of the production is lovingly, and unflinchingly, told in Mario Van Peebles’ 2003 film Baadasssss!, which was originally titled “How to Get the Man’s Foot Outta Your Ass.” In the biofilm Melvin Van Peebles pitches a story about a live sex show performer working out of a Los Angeles whorehouse who becomes radicalized. The studio withdraws its offer, and Melvin hits the streets looking for independent backing, nonunion crews, and nonprofessional actors. He ultimately finds his delivery system in a porn producer, played by David Alan Grier.

We can trust Baadasssss! in its accuracy, Mario Van Peebles is Melvin’s son, and plays his father in the film, just like he did in Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. The pornographic connection also resonates because Mario was 13 years old when he played the young Sweetback in the flashback segment which opens the film. The scene was censored in reissues because of the Protection of Children Act. Nonetheless, the production got around unions by disguising itself as a porn film, and was initially rated X by the MPAA when it first came out. Some theaters trimmed up to 9 minutes of sex before projecting the film. Ever an enterprising showman, Melvin Van Peebles used that to his advantage, hyping the movie as “Rated X by an all-white jury!” in promotions.

“No charge if you don’t like it!”

Melvin Van Peebles has been criticized for pushing the racist stereotype of the Black stud, but Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song is as much an incursion in the sexual revolution as it is in civil disobedience. The counterculture guerilla war isn’t only about burning cop cars to cheering crowds, it includes the erotic socialism of the era’s radical cinema. The film opens with sexual suspense: Close-ups of women hungrily eyeing a young African American boy as he eats. They don’t want what’s on his plate, though. The very next scene shows him come of age as a sexual prodigy. Sweetback grew up in a cathouse, where he was on the menu for the female clientele. This also establishes Sweetback as submissive sexually, even though he is the character who holds the most power in the film.

The next scene further subverts the sexuality. The establishing shot shows two women putting on an erotic live performance for an appreciative audience. One of the women is wearing men’s clothes, as well as a fake beard and a hat, before she strips down to just a bra. During the on-stage sex act, they are visited by “the good dyke fairy godmother,” an effeminate man who waves his magic wand and turns the bearded lady into Sweetback. Van Peebles blurs the lines of magic, reality and sexual identity. This is reversed later in the film when the biker gang remove their helmets and are revealed to be women. The director subverts the myths of black masculinity further by having Sweetback sexually submit into power after being forced to service them all before they let him go.

Van Peebles maintains he played the title role himself because no established Black actor would work for what he could pay, and because the character only has six lines of dialogue. He also couldn’t afford a stunt man, so Melvin performed all of the stunts himself, which also included appearing in several unsimulated sex scenes. The cinematic social commentator contracted a social disease during filming, and successfully applied to the Directors Guild for workers’ compensation because he was “hurt on the job,” according to Darius James’s 1995 book That’s Blaxploitation!: Roots of the Baadasssss ‘Tude (Rated X by an All-Whyte Jury). The director used the money to buy more film stock.

When Van Peebles started out in film, he figured he “could make a feature for five hundred dollars” because “that was the cost of 90 minutes of film,” according to James’ book. When the director was young and couldn’t break into a segregated Hollywood with his early short films, Van Peebles was invited to Paris by Henri Langlois, founder of the Cinémathèque Française. He released the short film Les Cinq Cent Balles (500 Francs) in 1961. Van Peebles taught himself the language and wrote a number of books in French. One of which he adapted into his 1968 feature debut The Story of a Three-Day Pass, which starred Harry Baird as Turner, an African American soldier stationed in France. He is granted a promotion and a three-day leave by his racist commanding officer. The film explores the psychology of an interracial relationship, while critiquing racial attitudes in France.

Inspired by the French New Wave cinematic movement, Van Peebles approaches the narrative with the invention which comes with necessity. Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song was photographed in a variety of formats, half the film was shot on 35mm negative, less than half shot on 16mm which was blown up to 35mm. The camera is mostly handheld and goes in and out of focus. The cinematography is distorted by split-screen effects, negative images, double images, stills and dissolves. The psychedelic desert montage superimposes the psychology of the perpetual outlaw over the radicalized street hustler. Sweetback breaks all the taboos and presents a breakthrough in its picture of social discord.

“You been stirring up the natives, kid?”

The biggest name on the credits is the film’s real star: “The Black Community.” The villain of the film is the occupying army. Van Peebles presents an uncompromising dramatization of a threatening, abusive police force which are an adversary to the citizens of the streets they patrol. The only thing the cops know about their beat is who to beat, and that can be anyone. Late in the film, the police kill a Black man they mistake for Sweetback, when the cops learn an innocent man was shot, one says “so what?”

Sweetback’s initial relationship with the police is cordial, the body of a Black man is discovered in his neighborhood, Sweetback agrees to accompany two white cops to the station as a suspect to make them look good. The trouble starts when the cops mercilessly brutalize the young Black Panther Mu-Mu (Hubert Scales). Sweetback fights back. The hustler-stud assaults the white plainclothes cops with their own handcuffs. The Black Panthers saw this as revolutionary solidarity, declared the film required viewing for all members, who filled theaters, and ensured the film’s box office victory.

Those Baadasssss Songs

One of Blaxploitation’s greatest contributions to the arts is the art of the soundtrack. Among its many precedents, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song was the first film to capitalize on the marketing appeal of its music. And what a soundtrack. Founded in Chicago by Maurice White in 1969, Earth, Wind & Fire were a rising funk ensemble. Peebles’ secretary, who was dating one of the members, convinced the director to contact the group. Peebles collaborated on the music, and also performed under his alter ego, Brer Soul, which was also the name of his 1968 debut studio album. The director projected scenes from the film as the band performed. The soundtrack album came out on the legendary Stax label in anticipation of the film’s release to raise cash and get the publicity of radio airplay.

Without the soundtrack, the film may never have made it into theaters. But the strategy worked so well, artists like Curtis Mayfield, Isaac Hayes, Marvin Gaye, Bobby Womack, Donny Hathaway, and James Brown were brought in to compose music for movies. Up until this time, Quincy Jones was the only Black composer with major motion picture scores to his credit.

Music is crucial to the film’s design. The songs on the soundtrack album incorporate the film’s dialog as an instrument. Side One begins with “Sweetback Losing His Cherry,” which alternates between a gospel choir and urban funk while a vocalist lets loose with the happy moans of sex. “Sweetback Getting it Uptight and Preaching it so Hard the Bourgeois Reggin Angels in Heaven Turn Around” is pure psychedelic cacophony.

“Everybody profits.”

Van Peebles’ direction is not rudderless. It is fearless. Like the helmsman himself, who jumped off a bridge nine times before a stunt was declared perfect. He even stood off against the Hells Angels, when bikers brought a knife to an almost-gunfight on the set, demanding to be let off even though they’d been paid for the day. The film boldly features the casual systemic racism of law enforcement, from a police commissioner using epithets on live TV to the deafening of Sweetback’s boss Beetle (Simon Chuckster) who is deafened during interrogation when a cop fires a revolver next to his ear. The film still all-too accurately portrays how the Black community is persecuted by police.

Because of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, the deaths of Martin Luther King Jr., Fred Hampton, Malcolm X, and even Billie Holiday and Sam Cooke are now examined through a harsher cinematic lens. Their stories are being told without the whitewashing of polite censorship. Films about them include indictments which Hollywood would never have dared to portray had Van Peebles not opened the door. But the realities of George Floyd, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Philando Castile, Trayvon Martin, and countless others continue to assault everyday senses. Fifty years later, the film retains its shock value, which has paid off in vast dividends.

The ending promises a sequel which never materialized, but came to life through the movement it began. Though tagged forever as the first Blaxploitation film, Van Peebles called it “the first Black Power movie.” The filmmaker had complete control, artistically and commercially, the very opposite of exploitation. Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song is a significant artistic, political and sexual statement, which is still revolutionary in the era of social justice warriors.