Ryan Lambie interview: science fiction, cinema, Moviedrome and more

We chat to Ryan Lambie about Moviedrome, sci-fi cinema, his new book, and a little bit of Doctor Who...

Never let it be said that this website would never, ultimately, eat itself and disappear up its own backside at the same time. Our much-loved deputy editor, Mr Ryan Lambie, has gone and written a book about his love of science fiction cinema. Thus, we decided to take the opportunity to give him a bit of a grilling, and put him through the terror and hell of a Den Of Geek interview. Honestly, chums, I’ve been waiting for a moment like this since I first met the man, over a decade ago.

Here, then, is Ryan on The Geek’s Guide to SF Cinema, the films that changed his life, and Jason Statham…

Firstly, congratulations on your book, that I gather is available at from lots of posh booksellers.

You and I have had lots of chats over the years about why science fiction cinemas has been so important in your own life. But can you talk about that? About the sci-fi films you discovered when you were young, and why they had such an impact on you?

Yeah. The one that first got to me… I remember coming home from school, and BBC Two had a series of films that they used to put on at four o’clock or something like that, teatime. I must have been nine or ten years old, and I remember the first one that really stuck in my head. It was a film called Invaders From Mars, and it was part of a season that was being shown on BBC Two, and I remember watching it and being transfixed.

What was it about that film?

It was jaw-dropping.

Aliens land in the field behind a kid’s back garden, and gradually infiltrate the family. There’s a flying saucer buried in the garden. The friendly dad goes all dark and violent, and in once scene, strikes the boy across the face.

For some reason that scene, and the whole first half of the film, completely engulfed my brain.

In any other genre, showing that going on in something going out at teatime on the BBC was a no-no in the 1980s. But under the cover of sci-fi, you could do that?

Yeah! And that’s what I realised. I had friends whose parents hit them, but I’d never seen it on screen. And here it was being talked about openly. So that’s an example of what sci-fi can do, I gradually realised: it can touch on subjects that wouldn’t be palatable, or difficult to look at. Like looking at the sun through a smoked mirror so you don’t get scorched retinas.

The other film that really got to me, the second one, was Silent Running. And that was the first time I’d ever cried at the end of a science fiction movie.

But not the last time?

No, no! And those two films, they really introduced me to science fiction. I mean, I grew up with science fiction, and I watched and loved Star Wars, and Doctor Who. But Invaders From Mars was the moment when I realised sci-fi could also be something else.

Back up. I never knew you liked Doctor Who! I’ve worked with you for a decade. You kept that to yourself!

I do like Doctor Who, but my memories of Doctor Who tend to be more visceral than detailed. And I couldn’t always get what was going on! Peter Davison was my Doctor, and I remember the regenerative… what’s that word?

Regeneration.

Yeah, that’s it! That’s what I said!

It wasn’t what you said.

It was.

It wasn’t. I’m going to quote you.

You’ll edit that out, though?

No, not at all. It’s going in.

Oh God.

But I used to watch shows like Doctor Who, and Star Trek, and could never quite remember when things happened in certain episodes. I always felt a bit silly talking about them.

Do you think there’s still a snobbery, and ‘I know more than you’ element in sci-fi fandom? Even as the films have got bigger and more widely seen?

I’m not sure it’s snobbery, but I do think there’s something. A kind of competitiveness. It becomes a bit like arm wrestling, where somebody knows a series or something in more detail than someone else. They can name the exact date that something had aired. I was never much good at that.

Turning to your book, one of the things I really love about it is that it goes to something you were saying before. I wonder if you feel this, too: that in television, there’s now a lack of curated sci-fi cinema. The irony is that today anybody could watch Invaders From Mars at 4pm on a weekday, but without anyone curating that, or directly scheduling that, they won’t. Things like Moviedrome aren’t around anymore, and I know you’re a huge fan of that show and what it did.

Yeah.

Can you talk about that lack of curation, and what you hope this book will do?

I never thought of it like that, actually. But yeah. I remember BBC Two put on that season of science fiction films, and I watched every one, just because of the name of the season. I saw all sorts of films I otherwise would never have seen. It was the same with Moviedrome, with what Alex Cox was doing.

Was there any other film that comes to mind?

There was a Russian film, actually, called Dead Man’s Letters. It’s kind of a Russian post-apocalyptic drama, really, about survival and death. It’s very downbeat, but it’s beautifully shot and haunting. It’s one of those films that stays with you for days.

That’s an example of a film I found while I was researching this book. I watched a whole bunch of Soviet films that I hadn’t seen before. And I hope that’s an example of what the book does. Of what curated TV used to do. That you recognise a few titles, but hopefully there’ll be a few in there that you haven’t.

In theory, Netflix is supposed to do that to a degree. But I always wonder if it funnels people a little too much.

The good thing about Netflix is that they’re obviously choosing things, and there’s an awful lot of genre stuff on there. The problem today is the sheer weight of genre stuff that’s everywhere. TV, Netflix, there’s so much to choose from, it’s difficult to know where to start.

And also, the problem with that algorithmic curation – people who liked this film also liked X, Y and Z – is that you tend to end up with the things that you already like, rather than stuff you might not have otherwise chosen. You’ll end up with something less interesting. You watch stuff in your comfort zone, rather than things that are different. I wouldn’t necessarily have sought out some of the films on BBC Two’s sci-fi series by choice, but they really affected me.

I’ve just opened up Netflix UK now, to see what that opening screen presents to you. There are a couple of thousand things in the catalogue to watch, but that front screen distils it down to, what, 100? And the most popular titles it’s presenting are the Peanuts movie, the Zoolander sequel, The Cloverfield Paradox and Fury. I don’t know how you begin to start looking for a Russian sci-fi film!

No, exactly. There’s an assumption now that people will just Google stuff, or find top ten lists. But even top ten lists tend to focus on some of the more obvious films.

It’s difficult I think, because of the amount of stuff there is. What you really want is the Alex Cox Moviedrome experience, where someone says ‘have you seen this? No? This is why you should watch it!’. That this is the person who made it, the context it was made in, this is where it fits into the broader filmmaking landscape. That’s something that Moviedrome taught me when I was younger, and that’s something that tends to be missing now from TV at least. And certainly from Netflix.

If BBC Two is reading, and there’s a commissioning editor looking for someone to curate a specially-chosen series of films, is your hat in the ring?

Yes!

If you’re reading, powerful BBC Two people: there you go.

Mark Kermode talked in his formative years about how he would go in and watch double bills in cinema, and have no idea what he was going to get. For those of us growing up outside London though – and London cinemas were brilliant for their late night shows – television was what we had, of course. That we didn’t have the wealth of choice available now.

Yeah. But I moved around a little when I was younger. I lived in a town at first, near a cinema, and going to a cinema always felt like a real treat – some of my earliest experience were of being taken to the cinema. Then we moved out to a smaller place, miles away from a cinema, and television really opened my eyes. But then the next thing was that my little town got its own video shop – one video shop! – and I used to go there so often that I was on first name terms with the owner, and he used to give me spare posters and stuff like that. I discovered loads of films from that video shop.

There’s no snobbery to your writing in the book. On the one hand, you’ve got a chapter talking about The Terminator, and by the end, you’ve chatted about Xenogenesis, Timecop and Déjà Vu. And Predestination! A movie you put me onto, if memory serves.

Presumably, the actual quality of the film isn’t always the vital ingredient in the film having an influence?

Yeah. I think one of the things we have on Den Of Geek that hopefully is part of our ethos is that a film doesn’t have to be great to be enjoyable. You can get value even out of a film that for 80 minutes is terrible, but for ten minutes has something incredible going on.

Like in Skyscraper, the Anna Nicole Smith version I wrote about the other day. The film as a whole is awful, but the stunts are amazing. The people who devised the stunts obviously cared about what they were doing. There’s one sequence in an alleyway that involves Uzis and rocket launchers and ridiculous balls of flame. It looks incredibly dangerous, and for that few minutes, the film comes to life.

There are films in the book as well that are a bit like that. Mad Max rip-offs, really low budget Mad Max variants from Italy or Spain. They’ve gone into the desert with some old cars, and some of them are great.

You got Waterworld in there! I checked! You didn’t entirely skimp on the Costner [important file note: I’m a huge Kevin Costner fan, and interest Ryan with this a lot]…

Yeah. Whether you like the film or not…

You know who you’re talking to, don’t you?

Oh God, yes. Let’s not do Costner! But whether you like it or not – and it’s obviously an incredibly expensive version of Mad Max! – it’s got things to it!

You picked 30 key films for the book, that revolutionised science fiction cinema. But is there are line there between the ones that had that impact, and your favourites? Do you like very film you’ve chosen?

No.

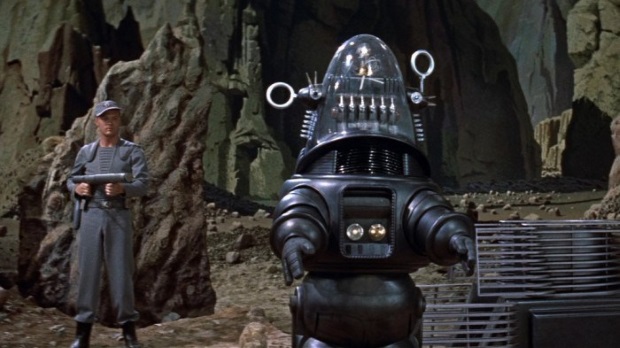

One of the driving things behind the book, one of the things I was thinking about when I was structuring it, was that if there’s one particular way that science fiction tends to be underrated is how it’s pushed the whole of cinema forward. In terms of storytelling, technique, the technical aspects of storytelling. If you go right back to A Trip To The Moon, and the editing tricks, the in-camera effects, they were quite revolutionary. You look at the make-up effects in Planet Of The Apes, they’re extraordinary.

A Clockwork Orange isn’t my favourite film in the book, and it isn’t even my favourite Stanley Kubrick film by a long chalk…

Are you allowed to say things like that out loud?

I don’t know!

We’ll find out…

Dr Strangelove is my favourite Kubrick. A Clockwork Orange is a film that made me feel really uncomfortable – which was probably Kubrick’s intention, in fairness. But one of the things that it did do, when you think about that it’s over 40 years since it was made, is that along with 2001 it showed two different sides of science fiction. That sci-fi could be taken seriously, and that it could be made in a way that’s sophisticated and disturbing, in A Clockwork Orange’s case.

It’s interesting that A Clockwork Orange came out in the same decade that David Cronenberg started making his body horror science fiction films, because his are very much science fiction too.

Sci-fi can be disturbing and visceral. It’s not just comfort food. It’s not just the equivalent of pulp magazines. It can aspire to be something more than… well, if you looked at what Hollywood studios thought science fiction was in the 1950s, it was considered to be second on the bill. Or worse, box office poison. The dabblings that Hollywood had, at least before the 60s, in science fiction weren’t terribly successful. Forbidden Planet was made with the budget of an MGM musical, but it didn’t do the numbers of an MGM musical. Just Imagine, that I think Fox made in 1930, was a disaster financially.

Do you think it’s in danger of becoming cyclical, now that films like The Cloverfield Paradox and Annihilation are having their cinema release curtailed in favour of going straight to a streaming service? Because of fear of box office?

I think there’s a growing nervousness around cinema in general, and a greater sense that the only things that can truly survive in mainstream cinema now are the big brands. The Disneys, Lucasfilms, Marvels, DCs… those are the things that can survive, and anything else is incredibly risky.

For a little while, when you had something like Inception, an original sci-fi heist thriller, when that does well, I think that emboldened the studios for a while. Something like Gravity, that did extremely well. But for every Inception or Gravity there’s a Jupiter Ascending or Passengers. Yes, they made money, but nobody got rich off those films.

Blade Runner 2049 only came out last year, already that’s starting to look like the product of another epoch. When you’ve got Annihilation and Mute going to Netflix, and to a much lesser extent, The Cloverfield Paradox, it’s starting to look like Blade Runner 2049 is the product of another era.

It could all come around again. It only takes one major sci-fi hit to embolden the studios to make other things in a similar vein. But at the moment it feels like a diminishing spiral. Look at what Guillermo del Toro said about The Shape Of Water. That filmmakers have to find ways to make films cheaper. One of the things that did for Crimson Peak was that he made it for $60m, and he said he should have made it for $20m. If sci-fi filmmakers do want a shot at getting something in a cinema they’ve got to find a way of making it for $20m. Even then, with multiplex real estate being taken up by event films so much, it’s difficult.

Before the PR person glares at us and tells us to shut up, two more questions. Firstly, can you recommend a film that you reckon 95% of people reading this haven’t seen?

I don’t know about 95%, but I’d go for Gattaca off the top of my head. It’s just a beautiful movie – wonderful performances from Ethan Hawke and particularly Jude Law – this was his first American movie, and possibly the best he’s ever been. A wonderful score. And it’s just a clever, elegant spin on the themes from Brave New World. I can’t tell you how much I love that film.

And finally – how else could I end? – what’s your favourite Jason Statham movie?

Oh God! I’m going to talk about one that nobody has mentioned so far, I don’t think. I’m going to go for The One.

You’re right, nobody goes for that.

It’s early Statham action, where Statham teams up with Jet Li. There are all these different multiverses and different Jet Lis doing different things in each. There’s the beekeeper Jet Li in one, an archaeologist Jet li in other, another who’s a bricklayer of whatever. And then there’s an evil Jet Li who’s going through all the different universes killing all the other Jet Lis until he’s the only one left. And the good Jet Li teams up with Jason Statham to take out Bad Jet Li. It’s like Highlander, but with one of Hong Kong cinema’s biggest stars, and one of London action cinema’s only stars.

You seem to be saying the words ‘Jet Li’ more than ‘Jason Statham’.

[Laughs] It’s one of the ones that doesn’t come up in conversation quite so often! I’m not saying it’s as good as The Transporter, but it’s great!

Ryan Lambie, thank you very much! Now get back to work…

The Geek’s Guide to SF Cinema is published by Little, Brown and is available now.