Megazone 23: The ’80s Anime That Tackled Simulated Reality Before The Matrix

Released in 1985, the anime Megazone 23 makes for an ideal companion piece to the Wachowskis’ 1999 hit, The Matrix...

When the Wachowskis were laying out their vision for what would become The Matrix in the late ’90s, they sat down producer Joel Silver and showed him a VHS tape of Ghost in the Shell – Mamoru Oshii’s classic anime adaptation of Masamune Shirow’s manga.

With The Matrix, the Wachowskis wanted to mix up a heady cocktail of Hong Kong action, cyberpunk, philosophy, eastern and western myth, as well as the bold stylings of Japanese and American comic books. But they also wanted to draw on the cool design, camera angles, and sense of dynamism seen in the best Japanese anime. Ghost in the Shell has certain story elements in common with The Matrix – most obviously the cyberpunk idea of physically jacking into a virtual space – but it seemed to be the aesthetics of the anime that really caught their eye.

When The Matrix emerged in 1999, its fusion of action, sci-fi, and edgy ’90s design (all tight black leather, wrap-around shades, and dual pistols) made it a colossal hit. The Matrix also helped popularize some of the John Woo movies and classic anime among western audiences. In interviews, the Wachowskis openly referenced the likes of Ghost in the Shell, Akira, and Ninja Scroll as inspirations for The Matrix. They even got to work with the writer and director of Ninja Scroll, Yoshiaki Kawajiri, in their 2003 animated portmanteau movie, The Animatrix.

One anime the Wachowskis didn’t mention, though, was Megazone 23.

Released in straight-to-video in 1985, Megazone 23 is a sci-fi action thriller almost as heady with ambitious ideas as The Matrix – and, perhaps coincidentally, the two share a number of similar plot points.

read more: Love, Death & Robots Review (Spoiler-Free)

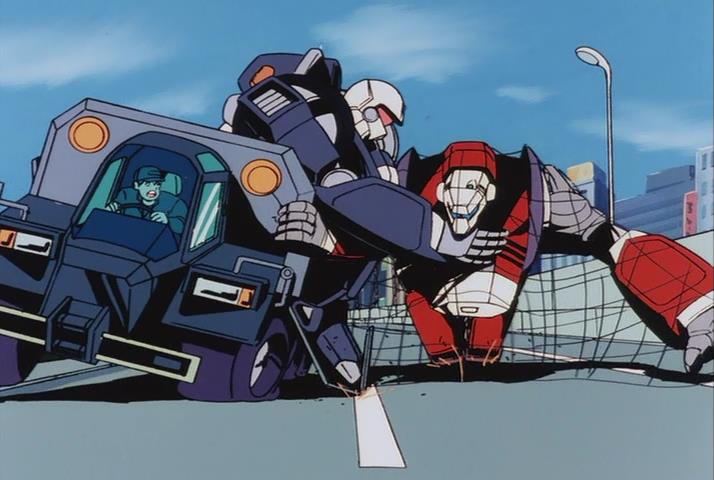

Directed by Noboru Ishiguru (a filmmaker who also brought us such classics as Macross and Space Battleship Yamato), Megazone 23 had just about everything you could want from a mid-80s action show: transforming robots, copious action, a hero with a cool bike, and like Macross, a curious fascination with Japanese idol singers. Stitching it all together, though, was a surprisingly smart sci-fi premise.

Shogo Yahagi is just your average Tokyo youth as Megazone 23 opens. He likes to hurtle around the city on his bike, hang out with his friends, flirt with ladies, and generally make a loud, shouty nuisance of himself. In what could be a bit of karmic justice, it’s Shogo’s motorcycle fetish that draws him into the story’s central conspiracy.

His best friend shows up one day with a stolen motorbike that makes his ride look like a Penny Farthing: it’s the size of a truck, appears to have a jet engine strapped to each side, and generally looks far more advanced than something humans could make in the mid-1980s.

Worryingly, Shogo’s friend stole the bike from a military installation he works at, and now there are assorted (heavily armed) government men in black on his tail. One bloody shoot-out later, and the friend’s dead and Shogo’s off on the stolen jet bike (called the Garland) with half of Tokyo’s cops and military types in hot pursuit.

As if all this wasn’t bewildering enough, Shogo then discovers that the Garland can transform into a giant robot. Subsequently, a military villain named BD tells Shogo the terrible truth: what he thinks is Tokyo isn’t Tokyo, but an exact replica floating through space in a ship. About 5,000 years earlier, Earth was rendered uninhabitable by a war with alien invaders, and so the remnants of humanity were sent off into space in giant arks. To keep everybody calm while Earth repaired itself, a perfect copy of Tokyo was made, circa 1985, and is ruled over by a sentient computer called Bahamut.

In short, Shogo’s realization is much like Neo’s in The Matrix: reality as he thought he knew it is a sham. It isn’t the time period he thought it was, and there are machines running everything. There are more minor similarities, too: the Men in Black who first try to retrieve the stolen bike are similar to The Matrix’s Agent Smith. Later episodes also introduce some mechanical aliens with tentacles that look not too dissimilar to the ones in the Wachowskis’ opus. It’s remarkable to think that Megazone 23 emerged well over a decade before The Matrix was even an elevator pitch.

read more: A Tribue to the Genre Work of Carrie-Anne Moss

Frustratingly, not everything about Megazone 23 quite hangs together, and for every brilliant idea – like a Japanese idol singer who turns out to be a holographic stooge created by the AI computer, or a character who wants to make a film about a simulated reality within the film – there’s a disjointed story moment or awkward character decision. A sex scene between Shogo and his dancer girlfriend, Yui, forms the backdrop for an ungainly slab of exposition. A Weinstein-like subplot involving Yui’s sleazy boss is raised, handled in a distinctly insensitive way and then thankfully dropped.A lot of these shortcomings are explained by Megazone 23’s unusual production history. It was originally conceived as a 12-episode television series, and a fair chunk of its action scenes was already drawn and animated in order to create promotional trailers. But when the studio lost its sponsorship, the producers decided to edit the story down to a more manageable 80 minutes and release it on VHS instead.

In the mid-80s, the straight-to-video market (known there as OVA or OAV) was still in its relative infancy and was better known for offering short, racier output that couldn’t be shown on TV. This is likely why Megazone 23’s animators threw in odd things like a predatory boss and a saucy love scene in a giant circular bed – “Too hot for television” scenes like these would help sell the thing on video. Unexpectedly, though, Megazone 23 was a huge success, becoming one of the key titles that helped popularize the OVA as a venue for more mature, less commercial anime than was permissible (or commercially viable) on television.

Even with the compromises and rough edges left from Megazone 23’s transition from TV to video, it’s still an absorbing and often quite dark sci-fi saga. There’s one character death that packs a real gut-punch and the conclusion is unusually sombre: Shogo rises up against the military might represented by his nemesis, BD, and crawls away from the battle bloodied and broken, his prized mecha-motorcycle shattered. It’s less like a crowd-pleasing ’80s anime and more like a classic samurai movie.

The art style and mecha designs are loaded with ’80s cool, too, since they’re the product of some of the same artists and designers who worked on the hit Super Dimensional Fortress Macross. This was handy for Carl Macek, the American producer who turned Macross and a couple of other Japanese shows into the US TV hit, Robotech. Together with Cannon Films, Macek started casting around for another anime to make into a Robotech movie, and he settled on Megazone 23, which, with its designs by the likes of Shinji Aramaki and Toshihiro Hirano, already looked like it had a connection to Macross. (Infamously, Cannon Films balked at Megazone 23’s emphasis on “girls talking” rather than robots fighting and forced Macek to splice in footage from another show, Southern Cross.)

Robotech: The Movie wasn’t a hit, but Megazone 23 still found a cult following among America’s nascent anime fan community. In Japan, the OVA was so popular that it sparked two more parts, released in 1986 and 1989, that were wildly varied in terms of art-style and storytelling, but still well worth watching. The middle chapter, in particular, offers some more heady sci-fi ideas we won’t go into here.

Given Megazone 23’s cult status and influence on other anime, you might be forgiven for thinking that it had a major bearing on the Wachowskis’ ideas for The Matrix. Interestingly, though, the pair stated in a 1999 interview that they’d never seen Megazone 23, much less co-opted its reality-destroying plot twist for their own sci-fi movie.

It’s likely that both the Wachowskis and the makers of Megazone 23 were drawing on the same storytelling ideas that worked their way into sci-fi a generation earlier, in the ’60s and ’70s. In Philip K. Dick’s novel, Time Out of Joint, for example, protagonist Ragle Gumm thinks he’s living in a 1950s suburb, but he’s actually living in a false reality: it’s really the late ’90s and Earth is at war with colonists on the Moon.

Dick, and other writers like him, helped popularize the notion of simulated realities in modern fiction. These ideas later found their way into such disparate ’90s movies as Peter Weir’s The Truman Show and Alex Proyas’ Dark City. The Wachowskis were simply exploring a similar arena to the one previously trodden by earlier storytellers.

read more: The Matrix Relaunch – Why an Expanded Universe Would Be a Good Idea

In Megazone 23, there’s what we might now call the Red Pill moment. If reality’s a simulation, then why did the powers that be choose the mid-1980s (or the late ’90s in The Matrix’s case) out of all the epochs in human history? BD has a simple yet quite brilliant reply: out of all the eras the computer could have chosen, the 1980s was the most prosperous. And, looking back at Megazone 23 now, we can see Japan in all its bubble economy pomp: the big hair, the shoulder pads, wall-to-wall idol singers.

It’s a neat moment, not unlike Agent Smith’s explanation as to why humans needed an imperfect reality in The Matrix (“human beings need suffering and misery”), and explains why Megazone 23 is something more than just another cheesy old show with robots in it. Like The Matrix, Megazone 23 understands that a fabricated world can be more comfortable, even seductive, than a real one.

As Shogo limps off, bleeding following his defeat at the hands of his enemies, it’s a wonder whether a part of him regrets taking that motorcycle and riding it down his own conspiracy-filled rabbit hole. Had he seen The Matrix, he might have remembered, with a wry smile, a line uttered by Joe Pantoliano’s character, Cypher: “Ignorance is bliss.”