High Fidelity: When All Your Heroes Are Terrible People

Alas, the geek idols of my youth have fallen...

This article comes from Den of Geek UK.

“Hi Rob. You f**king asshole.”

Rob Gordon is a great example of a character not having to be likeable to be interesting and entertaining (He made it to number 16 on our totally definitive list of the Top 50 assholes in cinema).

Yet you can’t help but root for Rob, because he’s played by John Cusack, and John Cusack can make hitmen sympathetic. Plus, as evidenced by the first article I linked to, I am in no position to criticize anyone for making endless lists. As you are reading a website called Den of Geek, there’s a chance you can also relate to Rob’s obsessive behaviour.

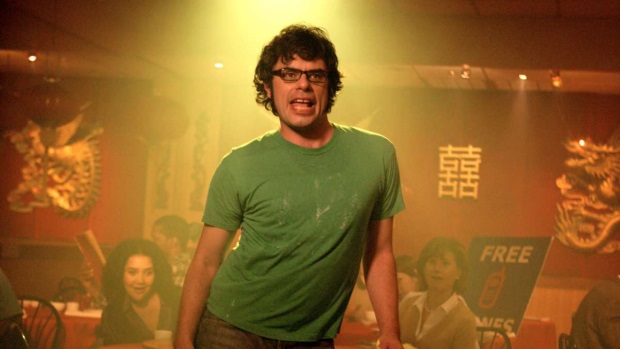

In both Nick Hornby’s novel and the adaptation, the characters are both funny and tragic. In the hands of less skilled writers and performers the comedy manchild can be really unlikeable (We’ll Never Have Paris and Liberal Arts for example), but the casting here is excellent with Cusack, Todd Louiso and Jack Black managing to turn petty bickering and bluntly obnoxious behaviour into entertainment. Their highlights for me are “Oh, oh, is she in a coma?” Louiso’s reacting faces, and Cusack screaming “I AM FINE NOW”.

Everyone gets a happy ending because it’s a comedy, but it’s not textbook romantic. In the end Laura (Iben Hjejle), who splits up with Rob at the start of the film for entirely sensible reasons, gets back with him because she’s “too tired not to be with you”. Rob, having striven for this result for half the film (to the extent of harassing her and her new partner) still takes time after this to realise that he’s not totally committed to her.

A lot of films about immature men mirror Trainspotting; a film concerning heroin users, the fact of its highs and lows was important due to its treatment of its subject matter – not glamorizing heroin but pointing out that there are obvious plus sides to taking it as well as significant downsides. We see the characters struggle to escape from their addictions. Sound familiar?

In High Fidelity’s case the film gets comedy mileage from Rob’s life, making it look fun (“I will now sell five copies of The Three EPs by The Beta Band”) but also bringing in the violent fantasies, the stalking, the breakdowns. The highs of destructive behaviour before the lows are the same as Trainspotting, yet few people talk of films glamorizing Being A Fucking Asshole.

“She’s right. I am a fucking asshole.”

For all its humor and affectionate observations High Fidelity does feature a group of men beating the crap out of someone for asking not to be stalked. Context makes it a joke, a comic highpoint, but it’s also unsettling when dwelt upon. Rob and Laura do get back together in the end, but rather than Cusack holding a ghetto blaster it’s after a war of attrition. After her dad’s funeral she effectively gives in, she settles, expressing it as the only available alternative to self-harm. You get the impression she’s not entirely joking.

But this lifestyle seemed aspirational: I wanted to be Rob Gordon when I grew up. I wanted to work in a record shop and care about music way too much and compile top five lists of things and act all superior when other people enjoyed The Beta Band. I also wanted to be Tim Bisley when I grew up. I wanted to have strange little adventures, live in my own flat playing computer games all the time and build a robot for fighting.

Teenage years are a time of emotional turbulence and a sense that your film, music, and TV choices really belong to you, that you have a specific and intense relationship with your favorites. I feel different now. It’s not that I feel embarrassed by liking these things as a teenager. I’m more embarrassed by how long it took me to notice that Rob Gordon literally describes himself as ‘a fucking asshole’ really early on in the movie, in a take that is very much borne out by the evidence and not remotely hidden in subtext.

I worked in a record shop and it was disappointing. When you meet someone who has similarly inflexible opinions about music as you, you are looked down on for this and realise what it must’ve been like for the people talking to you over the years. Likewise, when you meet the Tim Bisleys of fandom it can go badly. Sometimes you get Jaffa Cakes in his coat pocket Bisley, sometimes you get “No, are you gonna go? Now?”

Tim Bisley could now be on Reddit complaining that Rey is a Mary Sue and joining Incel subforums. However, I can’t say for certain that the teenage version of me wouldn’t feel the same. I was oblivious to my favorite characters’ flaws at that age, and was steeped in very white, very male fandom mindsets. I saw an aspirational figure in High Fidelity, and not a desperate raging manchild whose behaviour can tip over into harassment and violence. TV and movies offered me examples of Nice Guys who were unlucky in love, and I agreed without noticing their creepy, manipulative behaviour. Ross from Friends, JD from Scrubs, Xander in Buffy, the entire premise of How I Met Your Mother… I had backup from popular culture that doing likewise was fine.

Something that the book and movie of High Fidelity posit early on is the question ‘Did I listen to pop music because I was miserable, or was I miserable because I listened to pop music?’ Let’s transpose that to the behaviour of men in films. Are men in films arseholes because that’s what men are like, or are men like that because guys in films are arseholes?

If you think that sounds harsh, it’s the standard story arc for most male-led romantic comedies. The Man is an asshole. Kind of a funny asshole but an asshole nonetheless. He meets someone, they get together, then he’s too much of an asshole to make it stick, then realises that he loves her and needs to be less of an asshole to make it work. It’s a standard romcom plot. Consider Knocked Up, When Harry Met Sally, and Groundhog Day.

It was interesting (to me, at any rate) that a few people thought that the Ghostbusters reboot depicted men negatively, because the original doesn’t go out of its way to make Venkman sympathetic to begin with, and Walter-Friggin-Peck is the main antagonist (plus an excellent example of gender not being defined by genitals). Comedies get mileage out of their lead characters acting like selfish or ignorant dicks until they learn a valuable life lesson in the finale. The same initial dynamic is part of characters like Alan Partridge, where the audience is rooting for them despite their clearly doing and saying insensitive things.

“I AM FINE NOW.”

The difference between this and the 2016 Ghostbusters is that the male characters are usually positioned as the lead rather than/as well as a villain or opponent. More and more fiction is dealing with established, supposedly masculine characteristics, questioning and interrogating them.

Jemaine Clement, who excels at playing a variety of manchild characters both living and undead, has said he thinks being manchildren actually makes men better fathers because they can connect with their children better). Based on that same logic the same should be true of any parent. It isn’t that childish behavior is isolated to men (Paul Feig films, for example, don’t do anything vastly different to many other comedies except have female leads). It’s simply that men dominate pop culture, so we see more depictions of their immaturity. The blurring of the line between adulthood and childish things applies to all genders.

Part of the reason I’ve changed is that pop culture has confronted and challenged the attitudes that I held. Doctor Who was an important feature in my childhood, and when it returned it did a few things differently: the companion’s character was developed more than it had previously been, looking at their life outside of travelling with the Doctor and treating them as deserving of equal focus.

Fandom was changing, and it took me years to adjust, but the increased presence of other voices within it changed my thinking because I hadn’t sought these voices out or seen them before. Simply put, the more people have a voice, the more information we have to understand the world with, and as a result of hearing from more voices my opinions shifted.

This wasn’t without an initial period of doubling down on my previous stances, and certainly I haven’t just woken up one morning as a flaw-free individual. It’s an ongoing process, part of which involves making a decision. No one reacts well to being told what they believe isn’t correct, and indeed this can make you look for reinforcements. The choice is the same as the one Rob Gordon faces: either stay as you are, or pay attention to the potential of what’s in front of you.