The Beauty of The Godfather’s Long Takes

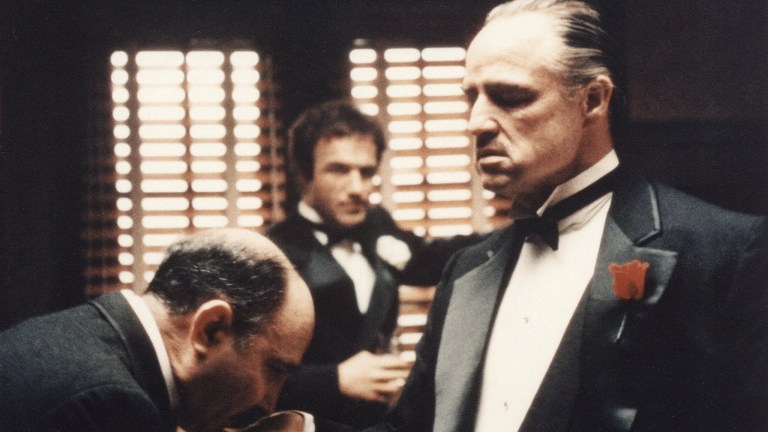

Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather is a masterpiece defined by intentional imperfections and lingering looks.

The Godfather, currently celebrating its 50th anniversary, is a perfect film. Every scene is an individual work of art. Francis Ford Coppola’s adaptation of Mario Puzo’s novel is never sloppy, but part of its olive oil charm lies in its blemishes. Some of the featured players were not professional actors, and uncomfortable scenes play out in lingering real time.

The Godfather has been criticized for glorifying violence, and it certainly has its share. From the barrage of bullets at a toll booth to the brains all over Michael’s Ivy League suit, plus waking up with the severed head of a beloved horse, the range of brutality is vast. There are scenes of domestic abuse which lead to street beatings. Car bombings vie with bar stabbings.

The reason the violence works so well, however, is because so much time is allowed to pass in between these scenes. The contrasting rhythms between family or business life and violent response intensifies the impact of the violence, but also mirrors the Corleone family. Blood is a big expense, and Coppola only spends it on storytelling.

Paramount Pictures released a 4K Ultra HD edition of The Godfather Trilogy on March 22. Overseen by Coppola, the three films were meticulously restored. This underscores one of the many things which made The Godfather stand out as a film for all times. It came together in the editing room, cut to what Paramount felt was a commercially viable length. William Reynolds and Peter Zinner were nominated for the 1973 Academy Award in Film Editing.

The anniversary edition of The Godfather Trilogy press notes say over 4,000 hours were spent repairing the films, with an additional 1,000 hours spent on color correction. Coppola shot 500,000 feet of usable footage for The Godfather. That is 90 hours of good takes. Out of that wealth of material, the editors still chose extremely long takes, uncut and in real time. These scenes define the film as much as any montage or edit.

An Unflinching Look

The Godfather begins with an uncut long take. Amerigo Bonasera’s opening monologue continues uninterrupted for four minutes. The first hard cut is when the title character, Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando), is revealed to be listening to the speech. This is a dangerous move. Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958) opens with a very long take as well, but it is choreographed through an elaborate set and tells a story through the imagery. Bonasera is telling his story to the godfather as a soliloquy, making his case alone.

Salvatore Corsitta, the actor who plays Bonasera, is not a star. He wasn’t even a professional actor, according to Mark Seal’s Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli: The Epic Story of the Making of The Godfather. Yet in some ways, he is the most featured bit player in cinema. He not only carries a static opening by himself, he establishes himself as the closest thing to the audience as we are likely to get.

“I believe in America,” the film begins. Bonasera is from the old world, but left the old ways. He is only now learning the new rules. When The Godfather came out, most of the country knew very little about the insular community of organized crime. Audiences understood stereotypes, morality plays, and crime capers. Bonasera never went to dinner at the Corleone household. His introduction stands in for the audience. He asks for death, and learns that is disrespectful. He expects cutthroats, but gets anisette.

The Godfather is a family film, and Coppola finds full arcs of tragedy within sentences. The solitary camera on Bonasera creates its own suspense. The funeral director doesn’t know what he is getting himself into, and every danger of his imagination plays out in Corsitta’s eyes. He doesn’t get a break. He is trapped in that scene, whether reliving his daughter’s agony, his own humiliation, or the shame he feels asking for a favor from a man he fears to be indebted to. That fear and uncertainty is very real. The man playing the funeral director had to keep his cool while sitting across from Brando, the actor who redefined acting. Coppola knew he would capture cinema verité.

Trapped in a Scene

Not all of the violence comes from gangland turf wars. One of the most brutal scenes in the film is a domestic dispute. The fight between the godfather’s daughter Connie (Talia Shire) and Carlo Rizzi (Gianni Russo) is also captured in one long take. The camera follows the pregnant and betrayed young wife from kitchen to dining room, to parlor, back to the kitchen, and into the hallway before there is a single cut. She destroys the entire apartment in real time until she is holding the knife before the scene cuts into the bedroom.

The editing’s similar hard cut leads to another real time scene where the audience is as stuck as Connie. Forced to play out “that little farce” as Michael would later put it, with an abusive husband and his relentless belt. It is harder to watch than any of the stylized violence because there is no reprieve.

The big shot Hollywood producer character, Jack Woltz, also gets no reprieve from the real-time horror which plays out as he is given his first and final offer from the Corleone family. The dead beast’s head came from a horse which was already scheduled to be killed by a dog-food company–so not for the film. It was delivered to the set, packed in dry ice, on the day of the shoot. John Marley, the veteran actor playing Woltz, had only rehearsed with a prosthetic replica. He wasn’t told what he would be uncovering. His scream is as real as the blood pooling under his feet.

The scene is set by increasingly menacing cross dissolves on the approach to the mansion. The long take of Woltz waking up, discovering blood, and finding the horse’s head, all within the same shot, is more frightening than slasher-film quick cuts. The audience is forced to watch the reaction in the deliberate cadence of reality. The camera stays on the head for two screams. After the second screen the camera pulls back, magnifying his solitude and powerlessness.

The sequence is as shocking as the shower scene in Psycho, for which Alfred Hitchcock used 78 camera setups and 52 cuts for 45 seconds of screen time. Coppola refined and redefined heavy editing in The Godfather.

The tollbooth scene where Sonny (James Caan) is machine gunned to death is a masterful nod to the extreme violence and non-verbal realizations of the final scene in Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde. Sonny leaves the Corleone compound in a homicidal rage and is calmed by the high-speed drive. He vents his anger on an open road before having to stop to pay the toll.

Good Deeds Go Unpunished

The cameras mirror Sonny’s consciousness, leisurely taking in the brief relief of keeping an eye on the road before he notices the toll collector drop to pick up spilled change. Then the cameras move frantically from his situation, to his perspective, to the encroaching danger. Eyes dart left, right, and center as the gunmen come into view, yet remain anonymously vague as the bullets which are tearing through the car’s interior. It is done in fully open space, and yet is cringingly claustrophobic until Sonny climbs from the car to be rendered virtually unrecognizable by machine gun fire.

The baptism scene is probably the most influential montage in motion picture history. Sergei Eisenstein first developed the “intellectual montage” for the film Battleship Potemkin in 1925. In Coppola’s lens, the strategy smarts even more in ‘72. Michael becomes godfather to the child of the man he is about to have killed. He renounces Satan, and all his works, while his assassins fill in for his idle time.

The use of religion as criminal subterfuge is a Machiavellian tenet. Every religious ceremony in The Godfather and The Godfather, Part II is a mask for high crime. Don Corleone bestows felonious favors during the opening wedding scene and plans crimes on behalf of his retainers; caporegime Tessio (Abe Vigoda) betrays Michael at Vito’s funeral.

In the sequel, Michael orders his brother Fredo killed during the funeral of their mother. Fredo says a Hail Mary when he drops a fishing line into the water before he meets his fate. Don Fannucci (Gastone Moschin) of the Black Hand makes a substantial donation at a religious street festival while young Vito Corleone (Robert De Niro) stalks him. But all family business concludes when Michael and Kay Corleone become the godparents of Connie’s firstborn son, Michael Francis Rizzi (played by an infant Sofia Coppola).

In Puzo’s book, Michael’s revenge takes 40 pages. The film expertly condenses them into brilliance through parallel editing. The scenes may be occurring simultaneously, but there is enough vagueness to allow extraneous timeframes. The cross-cuts highlight the sharp contrasts between the actions, Michael’s composure, and the baby’s cries. The moment after Michael is asked whether he renounces Satan, the first murder occurs. When the camera catches the new godfather affirm “I do renounce him,” we see a new renounceable action occur. By the time we hear the name of the holy trinity, the heads of the five families have been served on a silver plate.

The Godfather is edited in continuous action, passing chronologically through continuous action. Music is made by the space between the notes as much as by the tones themselves. For a crime film standard, long periods of time pass where no bloodshed occurs. This accentuates the effect of the violence while allowing deeper connections to be made with the players. Every death is personal. It makes good business sense, because the film and the viewer make an irrevocably emotional bond.

The Godfather Trilogy 4K Ultra HD edition is available from Paramount.