11 Movie Characters Who Should Have Just Called the Police

Never be too proud to ask for help. Especially if you’re being hounded by a serial killer.

A lifetime of watching movies should really be preparing us all to survive any real world crisis situation. Most of us probably know to never open a fridge door/bathroom cabinet with a serial killer on the loose, peer slowly into a dark hole, or spend the weekend in a creepy looking cabin. Movies have taught us plenty about what to do in an emergency, but the one thing they usually miss out is the first thing everyone should actually do.

Granted, most films would be incredibly short and boring if everyone just dialled 999 as soon as anything bad happened, but some characters would have been much better off calling the cops than dealing with everything on their own…

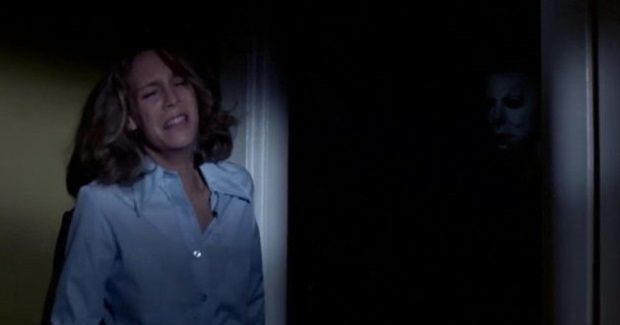

Laurie Strode, Halloween (1978)

In the first Halloween, Laurie is a 17-year-old high school student. Most of the film’s horror takes place in the background, without her knowing, but she still gets spooked by Michael Myers on three separate occasions. She doesn’t know at this point that Myers is an escaped mental patient with superhuman slashing skills, but she does know that he’s a terrifying guy in a mask who keeps stalking her around her own suburban neighborhood. If she phoned the police at the start of the film, they might have found Myers before he killed a bunch of kids and kick-started a 40-year franchise.

further reading: Halloween – The Ingredients of a Horror Classic

David Stevens, Shallow Grave (1994)

What would you do if you found your new roommate dead in his room? Call the police and fumigate? Nah, chop his hands and feet off, drive him out to the woods and bury him in a ditch, just so you can divvy up his money.

As often happens when a bunch of friends dismember the corpse of a drug dealer, things go from bad to worse for David, Juliet and Alex – with guilt and anxiety giving way to hammers and knives as one covered up death turns into a string of murders. Alex gets stabbed and arrested, and Juliet gets away with nothing, but David could have saved his own life if he’d just picked up the phone and done the right thing.

Hank Mitchell, A Simple Plan (1998)

This one’s a toughie. If most of us found $4.4 million in a crashed plane we’d probably take it too, without calling the police. If you phoned it in, there’s a good chance you’d never see the money again. On the other hand, the idea that no one is going to miss that much money (and a plane) is a bit ridiculous, so the smart thing to do would be to tell the authorities and hope for a reward.

Hank decided to keep it a secret, and he ended up having to kill an old man, his best friend, his best friend’s wife, an FBI agent and his own brother. And he didn’t even get to spend the money.

William Cleland, Blue Ruin (2013)

A lot of people do a lot things they shouldn’t in Blue Ruin. If Wade Cleland hadn’t murdered Dwight Evans’ parents in the first place, no one would have gotten hurt. But since he did, and since Dwight decided to kill him in revenge when he got out of prison, everyone had plenty of opportunities to put an end to the massacre that followed.

Key to the whole film is young William Cleland – the kid that sees Dwight kill Wade and decides to tell his murderous family instead of the police. Revenge is a dish best served by a qualified legal professional, not a mad man with crossbow.

Kevin McCallister, Home Alone (1990)

Possibly the most morally irresponsible kids’ film ever made, Home Alone taught an entire generation that the best thing to do if you hear a burglar breaking into your house is to attack them with Christmas baubles and Micro Machines instead of calling the police. Kevin actually does call 911 from his treehouse, but it’s the very last stage in his elaborate plan (and it would have ended up with his grisly torture if Old Man Marley didn’t turn up). Worse still, he does the exact same thing in Home Alone 2: Lost In New York.

Kale Brecht, Disturbia (2007)

Aside from having one of cinema’s most hilariously stupid names, Kale Brecht is also guilty of not reporting a lot of crimes in Disturbia – just because he’s worried that he might be paranoid.

Far less subtle than Rear Window, D.J. Caruso’s Hitchcock rip-off has Kale directly witness several obvious crimes, including seeing a dead body stuffed in his neighbor’s air-conditioning vent. The police actually do turn up several times throughout the film, but only because Kale’s ASBO tag alerts them that he’s left his own house. If he phoned the cops at the start of the film, he could have saved himself a whole lot of serial killer hassle.

Julie James, I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997)

Accidents happen. Julie and her friends should have been watching the road a bit more closely when they hit Ben Willis with their car – but they definitely should have just called the police when it happened (instead of rolling his body into the sea and invoking the wrath of an vengeful fisherman). If Julie had phoned it in, the paramedics would have seen that Ben was actually still alive. He probably still would have been a bit angry with the frat boys, but he likely wouldn’t have felt the need to murder them all with a fish hook.

Richard Parker, Weekend At Bernie’s (1989)

When Richard finds out that his boss is dead, he wants to call the police. Larry tries to convince him that it’s not a good idea, and that they might be better off pretending he’s still alive so they can still enjoy a weekend by the beach, and Richard is finally convinced when the hot girl from work shows up and wants to party.

Things might have just stayed a bit weird (and slightly gross) if everything went to plan, but the arrival of two hitmen forces Richard and Larry to spend the weekend puppeteering a corpse instead of enjoying the sunshine, proving that everyone would have been much better off had the police been involved from the start. (Especially Bernie.)

Paul Barnell, The Big White (2005)

If most of us found a body in a dustbin, we’d probably throw up. Crucially though, our next step would be to phone the police and let them know what we’d found. Paul Barnell, on the other hand, decided to pull it out, drape it in ham, and leave it out in the snow for the wolves to mangle enough to convince everyone it might be his long lost brother.

Yet again, The Big White proves that dead bodies don’t usually just appear from nowhere, and Barnell’s plan for insurance fraud starts unravelling when the thugs who put the body in the bin come looking for it – getting worse when his actual brother turns up alive (looking like Woody Harrelson).

Ray Peterson, The Burbs (1989)

Neighborhood watch schemes are a great idea – seeing concerned civilians looking out for each other, spotting vandalism and reporting crime. But Ray Peterson takes things a bit too far in The Burbs, investigating his neighbor (who is almost certainly a serial killer) on his own without bothering to tell the police.

When the old man across the street mysteriously disappears – and he spots oddball Hans Klopek burying something in the backyard – he decides to break into his neighbor’s house and investigate, resulting in him almost getting blown up. If he’d called the cops at the start of the film, Ray wouldn’t be known as one of cinema’s most famous busybodies.

Jack Burton, Big Trouble In Little China (1986)

“Cops have got better things to do than die!” says Jack Burton, running headlong into an epic street gang war that sees him fighting off superpowered Chinese hoodlums and evil ancient sorcerers in the San Francisco underworld. Most of the things Jack deals with probably wouldn’t have been handled any better by the police, but the film opens with him witnessing a kidnapping in the middle of the airport – which is clearly something that professional law enforcement is better equipped to handle than a smart-mouthed truck driver. But hey, “cops have got better things to do than die!”