The Forgotten Early Heroines of Video Games

Before Tomb Raider and even Metroid, these videogaming characters blazed a small trail in the 1980s...

It’s one of the great surprise endings in ’80s gaming. Having battled all the way to the end of Metroid and defeated the Mother Brain in five hours or less, the player’s treated to one of several cut-scenes, which reveal that the armoured character they’ve been controlling is – gasp – a woman.

When Metroid was released by Nintendo in 1986, this was a bold new concept. Characters like Street Fighter II’s Chun-Li and Tomb Raider’s Lara Croft were still years away, and if females were in games at all in the 1980s, they were usually hapless figures in need of rescue – the closest anyone had previously come to a proper female lead was Ms. Pac-Man, the hungry yellow sphere with a little red bow on her head, or maybe the protagonist of Girl’s Garden, a Japanese-only Sega game about collecting flowers to attract a boyfriend.

Check out the Logitech G513, the Perfect Next-Gen Keyboard for PC Gamers

Metroid’s Samus Aran, on the other hand, was a tough bounty hunter in a high-tech battle suit – quite a contrast to, say, Super Mario Bros’ Princess Peach.

Reportedly taking inspiration from Ridley Scott’s 1979 film Alien, the developers of Metroid decided to give their game a female protagonist midway through development. “Hey, wouldn’t it be kind of cool if it turned out that this person inside the suit was a woman?” a member of the team asked. And thus, what is commonly thought of as the first video game heroine was born.

But this isn’t strictly true.

In July 1985, a full year before the release of Metroid, Namco released a largely forgotten arcade machine called Baraduke. A free-scrolling shooter, it actually has quite a few elements in common with Metroid: it’s set in a network of caverns overrun by floating, globular aliens, which look quite a bit like the energy-sucking Metroids in Nintendo’s game. The central character’s an armoured space warrior bristling with weaponry. And in a congratulatory screen at the end of the game, the protagonist, named Kissy, is revealed to be an auburn-haired woman.

If Baraduke was a success for Namco at all, it seemed to be restricted to Japan; a sequel appeared in Japanese arcades in 1988, and the original game was ported to one solitary home computer – the Japan-only Sharp X68000.

Baraduke’s protagonist, however, lived on in other games Namco games, where she was given a charmingly convoluted backstory. Kissy’s full name is actually Toby “Kissy” Masuyo. She married the main character out of arcade hit Dig Dug, had a child who would become the central character in Mr. Driller, and then got a divorce. Kissy’s cameos have included Namco X Capcom, an RPG, as well as her son’s Mr. Driller series.

Curiously, that very same month – July 1985 – another Japanese arcade company came up with a video game heroine of their own. City Connection was a quirky yet endearing mix of platformer and driving game, in which the player, strapped into a tiny Honda City car, hurtles around each level painting the roads white. In practice, City Connection is a little bit like Q*Bert, in that it involves coloring platforms the same colour to complete a stage, but with its constantly-scrolling screen and relentless turn of speed, its pace is more akin to Namco’s cat-and-mouse cult item, Mappy.

What separated City Connection from all the other simplistic, quick-fix arcade games of the era was its presentation and backstory; behind the wheel of the player’s car is a blue-haired heroine named Clarice, a speed-obsessed thrill-seeker who’s relentlessly pursued by the cops as she travels from one capital city to another.

The game was popular enough to get some decent home ports, including the NES and ZX Spectrum, though some of western versions rather unfairly chopped all trace of Clarice and made the driver male instead. The Japanese version on the NES (or Famicom) gave Clarice a prominent showing in its TV commercials, though. Just look at the ’80s anime in evidence here:

City Connection doesn’t show up all that often on modern consoles in the 21st century, but vestiges of it still linger; an updated version of Jaleco’s cartoon shooter Game Tengoku, released in 2017, featured Clarice as a downloadable player character.

Between them, Clarice and Toby “Kissy” Masuyo seems poised, to steal Samus Aran’s crown as the first fearless heroines of gaming. But there’s a problem: Sega got there a few months earlier.

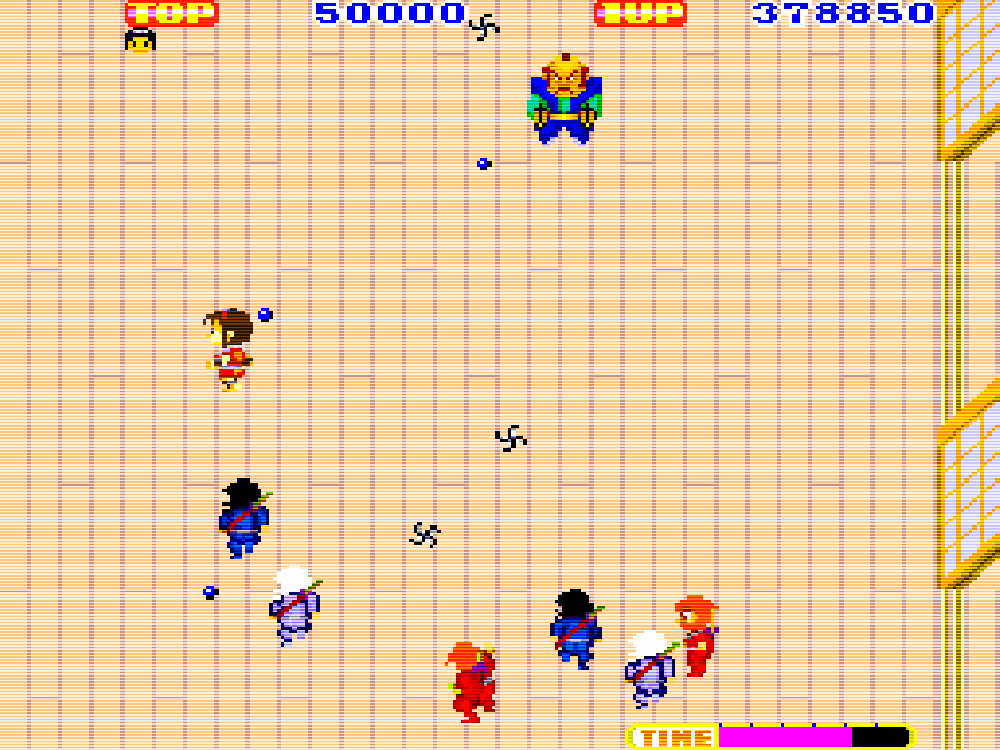

In March 1985 – around four months before the launch of Baraduke – Sega released an arcade machine called Ninja Princess. An effervescent and very tough up-the-screen shooter, it featured a princess who swapped royal robes for a warrior’s garb and went off on a run-and-gun adventure across the Japanese countryside. Princess Kurumi was handy in a fight, too, thanks to her powers of invisibility and ninja star-throwing abilities – though she did have the disarming tendency to burst into tears when struck by the enemies crowding onto the screen.

Ninja Princess was designed by Rieko Kodama, one of a small number of female figures working in the Japanese games industry in the 1980s. She later found wider fame as the creative force behind dozens of classic Sega games, such as Altered Beast, Phantasy Star, and Sonic The Hedgehog. She was still a new, 21-year-old employee when she designed the characters for Ninja Princess, and it’s likely that she created Princess Kurumi as a protagonist other female gamers could identify with.

The notion of a game led by a heroine seemed to make some sectors of Sega nervous. Outside Japan, Ninja Princess was renamed Sega Ninja – seemingly because Sega thought that the original title might put off a male-dominated arcade scene.

Ninja Princess was later ported to the SG-1000, Sega’s first foray into the console market, which remained a faithful port of the original. But by the time Ninja Princess had made its way to the Sega Master System console in the west, Ninja Princess had undergone a major series of changes. Now simply called The Ninja, the game had lost all traces of Princess Kurumi.

The vivacious cover art of the Japanese version, with its leaping, crimson-clad heroine, was gone, and an image of an anonymous (and distinctly masculine) shuriken-throwing ninja was put in its place.Within the game itself, Princess Kurumi was transformed into a male character, named in its lengthy opening story as Kazamaru. Just to rub salt in the wound, Kazamaru’s objective was – you’ve probably guessed it – to rescue a princess from an evil warlord.

Princess Kurumi is, therefore, one of videogame history’s great lost heroines. She was tough, but unlike the armoured warriors of Baraduke and Metroid, she was also relatably human. And at a time when most games were about defeating alien armadas or rescuing damsels in distress, Ninja Princess had a beguilingly forward-thinking, girl-power plot: the princess’s castle was seized by the evil Gyokuro Zaemon, so Kurumi set off to claim it back by herself.

Nintendo may have created the first truly celebrated heroine in gaming with Samus Aran, but Rieko Kodama, and her plucky Ninja Princess, made videogame history a full year earlier.