Steven Spielberg’s History with Video Games

Ahead of Ready Player One, we look at director Steven Spielberg's long-time fascination with video games...

In 1982, Steven Spielberg was at the height of his filmmaking powers. He’d changed the Hollywood landscape with Jaws; enjoyed huge success with Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, and Raiders Of The Lost Ark, and he was about to release his biggest film to date withE.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial.

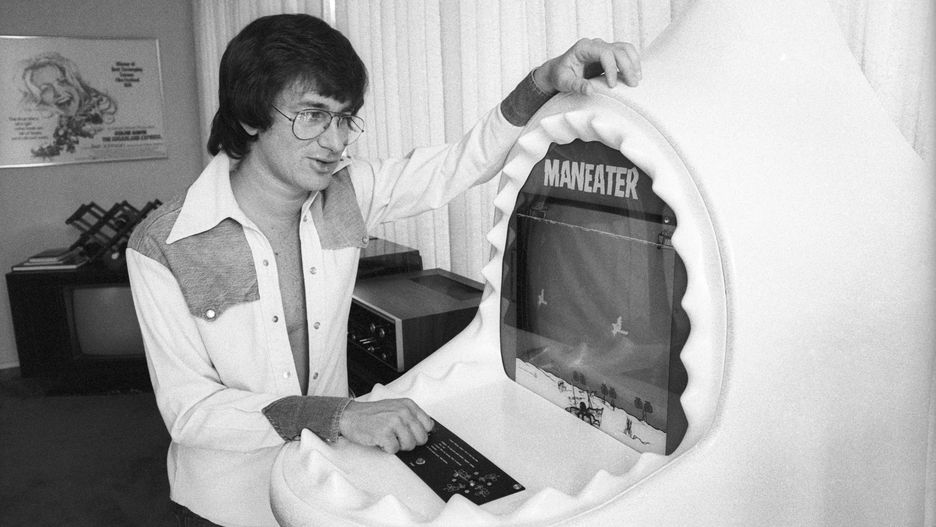

A photo taken at the time shows a 30-something Spielberg slouched in his office, surrounded by some of the trappings of his success: framed posters of Jaws and Close Encounters, and signed copies of E.T. draped over a table. But the photo also reveals something else about Spielberg – something that a lot of cinema-goers probably didn’t know at the time: he was really into video games. The evidence is right there over the director’s shoulder: a full-sized Donkey Kong cabinet, a hit arcade game that had only appeared in America a few months earlier.

Given the expense of such a machine, it’s fair to say that it didn’t end up in Spielberg’s office by accident – and neither is it the only time the director had shown off his collection of arcade games to photographers. Years earlier, he donned a pair of shades and posed for a photo next to his Missile Command cabinet; another photo shows Spielberg – now bearded and wearing Chinos and a leather jacket – at the helm of his Space Invaders machine.

Spielberg’s ’80s passion for gaming went further than just playing them in his spare time, however. As Slashfilm pointed out a few years ago, Spielberg wrote the introduction for Martin Amis’ unusual (and now very rare) book about his addiction to space invaders. And then, of course, there was E.T: the videogame.

Not only was E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial one of the biggest films of the 1980s, but it also indirectly sparked one of gaming’s first urban legends. Atari’s spin-off game, hastily put together in time for Christmas 1982, was so poorly received – and produced in such huge quantities – that its creators ended up with thousands of unsold copies. And as the market suffered a nasty slump in North America, word got around that those unsold E.T. games were quietly being buried in the New Mexico desert.

It almost sounded too wild to be true, yet the legend was revealed to have more than a grain of truth behind it: in 2015, the documentary Atari: Game Over covered a kind of archaeological dig at the rumored burial place of those E.T. games, and sure enough, a number of copies were recovered, along with other unsold Atari 2600 cartridges that were discarded in the wake of the early-80s crash.

Although he wouldn’t exactly rush to bring the subject up in interviews, E.T. director Steven Spielberg had at least a small hand in that ill-fated videogame. While the design and programming of E.T. was handled by Howard Scott Renshaw, who produced the thing in a dervish of all-night coding, Spielberg himself had reportedly pushed for a videogame. When Renshaw agreed to make the game, he met with Spielberg on a private jet to pitch his idea: a 2D adventure game that takes place in a complex world of interlocking screens. Spielberg had reportedly expected a Pac-Man clone; nevertheless, he was clearly convinced by what Renshaw proposed – the programmer even stipulated that Spielberg play the game and sign off on it before its release.

Around the time of E.T‘s release, Spielberg appeared on television and briefly praised the game based on his hit movie. “I was amazed at how difficult it was and at the same time how much fun it was to play,” Spielberg said. The general public, certainly at the time, didn’t exactly agree.

Despite E.T.‘s gloomy fate, the game’s story is almost as ingrained in 80s popular culture as Spielberg’s movies. Whether he directed them, like E.T. or the Indiana Jones movies, or served as producer, like the Back To The Future trilogy or The Goonies, he had a hand in some of the most quoted and referenced bits of pop entertainment of that era. It’s doubtful, in fact, that Spielberg himself could have predicted just how enduring all of these movies would prove to be; what once might have looked like an ephemeral children’s adventure – The Goonies – is still popular even in the 21st century. It’s telling, too, that all of the films mentioned so far have received videogame spin-offs – some dreadful, like E.T., and some very good, like The Goonies on the Nintendo Entertainment System.

Affection for Spielberg’s movies runs deep in Ernest Cline’s best-selling book, Ready Player One, which is all about a virtual world steeped in ’80s culture. It’s fitting, then, that Spielberg should end up as the director of its adaptation; it’s the post-modern serpent nibbling on its own tail. More than a chance to reference his own classic movies, Ready Player One may also give Spielberg the belated opportunity to speak to his affection for videogames – an affection that endured long after the E.T. videogame in the early ’80s.

In the mid-90s, for example, Spielberg joined forces with LucasArts to create a point-and-click adventure game, The Dig. The previous decade, the concept had begun life as an episode in Spielberg’s anthology TV series, Amazing Stories; about a group of scientists who investigate the evidence of an alien civilisation on an asteroid orbiting Earth, it was deemed too expensive to make as a television show, or even a movie. Instead, Spielberg reworked the idea into a game with sci-fi author Orson Scott Card. The Dig wasn’t quite as warmly received as some of LucasArts’ other hit adventure games, but it was still recognisably a Spielberg story: its sense of fear and wonder in the face of the unknown has a clear link to Close Encounters Of The Third Kind.

While The Dig wasn’t a hit, it was still a more satisfying experience than Steven Spielberg’s Director’s Chair – a kind of filmmaking simulator released in 1996. Featuring full-motion video clips of celebrities like Quentin Tarantino and Jennifer Aniston (back when such a thing was still a novelty), it tasked the player with guiding a fictional movie from its script stage, through post-production and onto release. In real terms, this simply meant splicing together a bunch of pre-recorded clips. A classic it was not.

The mid-90s also saw Spielberg get involved in another videogaming venture: Sega GameWorks, a kind of Planet Hollywood for videogames. Spielberg reportedly offered a certain amount of creative input in GameWorks (“I’m an addicted game addict, I always have been, and that’s the reason for my involvement in Sega GameWorks,” he said at the time), though he and his company DreamWorks eventually withdrew from the project in 2001.

All of this might imply that Spielberg’s involvement in the games industry failed to generate much creative heat – but then, we haven’t gotten to the first-person shooter phase of his career yet. Not long after he directed the acclaimed WWII film Saving Private Ryan, Spielberg and his team at DreamWorks Interactive began thinking about porting the realism of that movie into a videogame. Saving Private Ryan‘s celebrated opening sequence brought a quasi documentary feel to the Allied assault on the beaches of Normandy; what if that intensity could be recreated on a computer or console? The result was Medal Of Honor; published by Electronic Arts, it was a hit shooter that went on to redefine the whole genre. Spawning a series of spin-offs and sequels, the series’ influence spread further when several of its creators went off and made a rival game, Call Of Duty. Spielberg therefore unwittingly helped to create one of the biggest videogame franchises of all time.

Nor was this Spielberg’s only collaboration with EA. In 2005, the director signed a contract with the publisher to make three videogames – a high-profile deal that saw Spielberg get an office in EA’s headquarters. First came Boom Blox, a Jenga-like action puzzler for the Nintendo Wii; designed by Spielberg himself, the game was well received but, on a console crowded with sub-par shovelware, the nifty little title was somewhat lost in the mix (it did, however, get a sequel – the even more obscure Boom Blox Party).

Spielberg’s other project at EA was far more ambitious: codenamed LMNO, it was billed as a triple-A action adventure with a story that contained vague echoes of E.T. It concerned an ethereal, apparently female alien named Eve, who manages to escape from an Area 51-like secure facility in the desert. A male protagonist, Lincoln, has a chance meeting with the visitor in a diner, whereupon the place is set upon by heavily-armed government agents. This would form the basis of a single-player action game where the player cooperates with a computer-controlled side-kick; not unlike the Japanese cult game Ico, LMNO pivoted on creating the illusion of a flesh-and-blood character that was alternatively vulnerable and powerful – the alien’s telekinesis would serve as a useful tool at decisive moments in the story, if only the player can coax her into using them. Spielberg had planned to create a compelling emotional journey for the player, too: he famously hinted in an earlier interview that he wanted the game to elicit tears from its audience.

Sadly, LMNO would never get far beyond the prototyping stage, and despite its initial promise, Spielberg’s tear-jerker quietly withered on the vine.

A direct hand in game design aside, Spielberg has long incorporated cutting-edge computer tech in his movies. In the pre-digital days of optical effects, he worked with the VFX genius Douglas Trumbull to create Close Encounters Of The Third Kind’s spectacular finale; it was the kind of go-for-broke visual fireworks display that, had it failed to pass muster with audiences, would have brought the entire film tumbling down. Instead, Trumbull’s sequences of UFOs descending on Wyoming were a triumph, and the film was a colossal hit.

Jurassic Park, meanwhile, was among the 90s films that ushered in a new era of CGI; its sequences of computer-generated dinosaurs were brief, but melded with the animatronic effects almost seamlessly. Even as Spielberg’s entered the later stages of his filmmaking career, he’s remained undaunted by technological advances. Minority Report’s CG-heavy future world of virtual interfaces and ubiquitous advertising were heavily copied elsewhere; Spielberg even managed to fit in an all-CGI Tintin movie alongside War Horse in 2011.

All of which brings us back round to Ready Player One – a project that we might have imagined would go to a younger director more steeped in hectic action sequences (at one point, Chris Nolan was courted for the role).

Then again, it shouldn’t be too surprising that Spielberg would go for a movie about VR and all-enveloping pop culture. With the likes of Jaws and Raiders Of The Lost Ark, he and George Lucas pretty much wrote the rule book for modern blockbusters. But while his success in the world of interactive entertainment has been mixed, the liked of the infamous E.T., and the huge impact of Medal Of Honor mean that Spielberg’s helped shape the videogame landscape, too.