Revisiting Grange Hill: The Computer Game

In 1987, the strange and bleak Grange Hill: The Computer Game came out on the Commodore 64 and ZX Spectrum...

You’d been given the annual for Christmas. You’d taped the single off the radio. You’d had that special dream about Mrs McClusky, the details of which you didn’t divulge to a soul for twenty years until one night in the pub after which all your mates started calling you Bridget. It was the universal Grange Hill experience, shared by one and all.

In 1987, you couldn’t get enough of BBC TV series Grange Hill. When the licensed video game arrived for the Commodore 64 and ZX Spectrum, you marched your birthday money down to Boots and bought a copy. You put in the cassette, typed ‘Load’, opened a bag of Smiths Flavour ‘n’ Shake for sustenance, and embarked on a journey with hope in your heart.

Hope that was immediately shat out of your heart when you realised that your character options for Grange Hill: The Computer Game were limited to one, and that one was Luke “Gonch” Gardner.

Remember Luke “Gonch” Gardner? With no dispespect to him, he wasn’t Tucker Jenkins or Roland or Zammo or one of the Grange Hill allstars. (In a well-publicised and complex behind-the-scenes rights battle, those characters were all DC properties back then and therefore not available to Bug-Byte, the makers of Grange Hill: The Computer Game.)

When Justin Lee Collins publicly harassed the former stars of the show to reunite on Channel 4, he didn’t even ask Luke “Gonch” Gardner, a ginger Del-Boy who ran a string of get-rich-quick schemes. Do you know who I mean yet? Gonch was mates with “Hollo” Holloway. He sold toast at school for 10p a slice until his mum stopped him. You’re starting to form an image of his face.

If you played Grange Hill: The Computer Game at the time, you’ll definitely remember Gonch. Those memories won’t be good ones.

It’s hard to have good memories of playing Grange Hill: The Computer Game because the whole thing’s infused with a sense of eternal bleakness. Grange Hill creator Phil Redmond intended his TV series to deal with the real-world issues faced by London teenagers, and it did. Racism, drug addiction, teen pregnancy, crime… all human life was there.

Grange Hill: The Computer Game goes several steps further than that. It’s set in a lethal urban desert made up of such locations as: “an old sewage tank”, “a patch of waste land covered in rubbish”, an insalubrious canal, a bin store, a smelly subway “that stinks” and “the edge of a wall near the old-age pensioners’ flats”.

One of the first things Gonch does in the game is hoist himself up on top of a telephone box in which the glass has been smashed out. Gonch does a lot of climbing in the computer game; it’s his response to living in an environment that would make Ken Loach feel the need to smarten the place up with a few doilies before filming there.

“It doesn’t look as though anyone is going to fix the phone box, but with the windows out, it makes a great ladder” says the game in a sad indictment of Thatcher’s Britain. Backed by a minimalist city skyline, Gonch is always on the lookout for potential risks. “The old-age pensioners’ flats. You can’t see behind the wall, but how could there be any danger here?” he’s asked.

As he walks around this realm of existential threat, Gonch collects an assemblage of strange and pitiful items. A broken chair leg, a paper plane, a dead cat, a set of false teeth, a glass eye… He’s not so much a schoolchild as a scavenger in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road.

Why does Gonch want all those things? It’s hard to shake the suspicion that he’s trying to build himself a loving adult who’ll not murder him with a rolling pin, like his mum does if you walk left off the start screen.

Gonch’s mum’s fearsome child-rearing tactics are the catalyst for the game. The premise is that our hero had his Walkman confiscated at school for listening to it in lessons. It’s not the first time this has happened and his mum, as we’ve seen if we walked left off the start screen, will kill him if he comes home without it. That means it’s up to Gonch to break into Grange Hill and retrieve said item.

Gonch doesn’t assemble a band of well-wishers and hearty fellows to accompany him on his quest. He takes Hollo. Hollo only goes because he’s an ambulance-chaser and anticipating disaster. He hinders more than he helps, dragging his feet and slowing Gonch down and generally humphing about what a waste of time this all is.

Gonch and a lagging Hollo make their way through the urban landscape, falling foul of the many traps that lie hidden within. Fatal traps, I should say. Trip over a loose paving slab? Gonch dies. Fail to navigate a gap in the wall behind the old-age pensioners’ flats? Gonch dies. Walk into some concrete bollards? Gonch dies. Try to pat a dog? Gonch dies. (“That wasn’t a very clever idea” says the game, “Rolf has savaged your leg, and now you will probably die of some horrible disease”.)

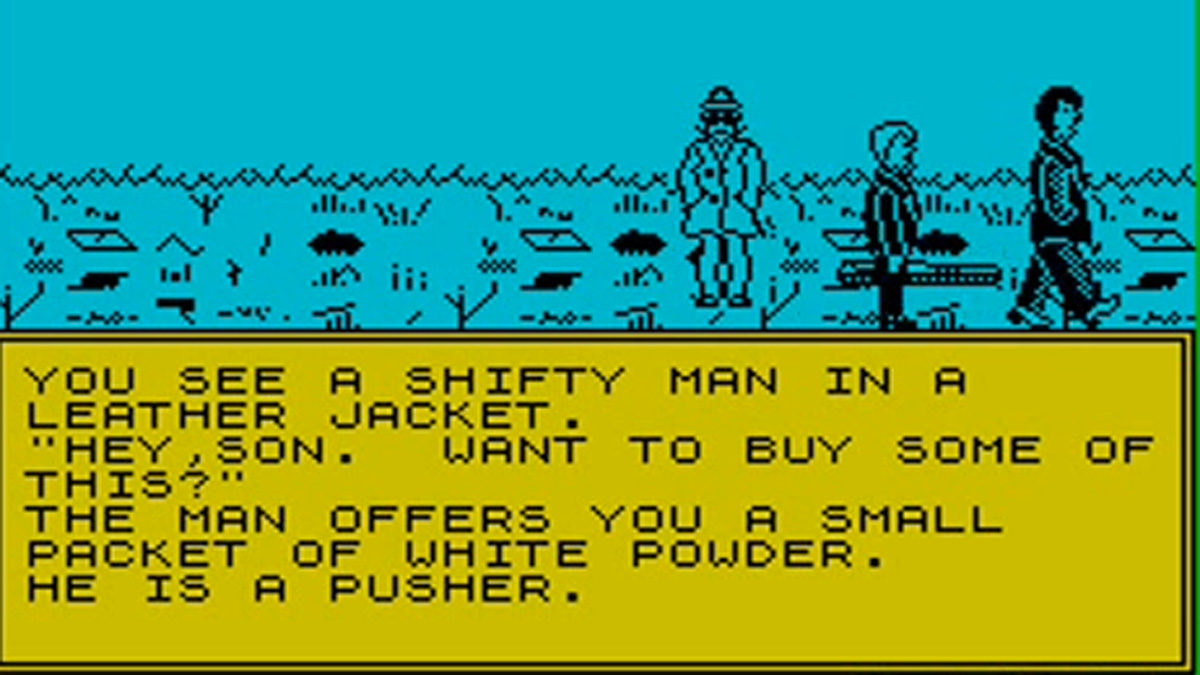

Another way Gonch dies is by scrolling down to ‘Yes’ when approached on the patch of wasteland covered in rubbish by “a shifty man in a leather jacket” who offers to sell him a bag of white powder. Purchase this fellow’s wares and Gonch doesn’t only die but stars in his own Irvine Welsh short story. “There is an empty look in his eyes as he snatches the money from your hand. His face is pale and drawn, his body thin and unfed. He steals to keep his habit, and makes addicts of children. He is dead, and soon you will be too,” says Grange Hill: The Computer Game.

It’s not only civil engineering faults and gaunt spectres of addiction that lay waste to Gonch in this barren disaster zone, magic realism is also employed to cover all terrifying bases. When Gonch spies a set of false teeth on the ground, you’re primed for whimsy. What you get, if Gonch walks over them, is more death. The abandoned gnashers leap up and snap at him, the result being—you guessed right—Gonch dies. Survive those and waiting for him on the next screen is a glass eyeball, on which, if he doesn’t pick it up first, Gonch will slip and die. The human prosthetics are stranded around the periphery of the oft-mentioned old-age pensioners’ flats, either flung out of windows by the residents to alert absent carers that they’ve fallen over and cracked a hip, or the remnants of dissolved corpses after they elected to simply lie down by the edge of the wall by their flats, and die.

It’s difficult for Gonch to pick up these macabre items, as he walks around a picture of disaffection with his hands in his pockets. A game about poverty both spiritual and financial, Gonch is part of a lost generation in which the only medium of creative expression afforded is “The Speaking Wall – where anyone can write, draw or spray anything about anyone at any time during school hours.” Even sadder is that the only thing written on the Speaking Wall are three solitary letters spelling the name Mat.

Whither Mat? You never see him. The only people Gonch meets apart from his mum and Hollo are Grange Hill school bully Imelda, from whom the presentation of a dead cat is the only possible escape, and Mr Griffiths the caretaker, who, if he’s not careful, kills him.

Should Gonch survive the gamut of traps on his way to break into school, he smashes a padlock into the boiler room, then spends much more time than is necessary climbing through the duct system like John McClane with fewer pubes. Upon arrival outside the Staff Room, where he spies the Walkman of which all this has been in aid, he realises the door is locked. Good job he brought Hollo with him, because Hollo, we learn, happens to have the key to the school staff room with him at all times. What kind of arrangement he made with Mr Bronson to access that perk, I wouldn’t like to imagine.

In goes Gonch to retrieve the Walkman and then run the gamut in reverse and present it to his abusive mother. Gonch’s mum however, has forgotten all about this Walkman and is only worried about claiming the insurance for a previous one he’d reported stolen at school. Gonch realises that if his teachers receive the insurance form for the old Walkman, they’ll remember about his confiscated Walkman and notice it’s missing. There’s only one thing for it: in a moment of supreme Sisyphean irony, he’ll have to go back to school to put it back where it was. And then, to round off an awful day, Gonch dies.

You won’t have known that though. You’ll have given up because you kept being killed by the bloody false teeth, and loaded Jet Set Willy instead.