Konix Multisystem: the British console that never was

It promised arcade-quality graphics and an ingenious control scheme. We look back at the sadly unreleased Konix Multisystem...

“What looks better than an Amiga, costs less than an ST and has more rock and roll than Afterburner?”

So ran the cover headline on the March 1989 issue of Ace Magazine. Beside those cryptic words sat a very odd looking piece of hardware: a black, plastic yoke like something taken from an aeroplane, with inviting red fire buttons mounted on the top of each stick. The black yoke was mounted on a blocky grey stand, which in turn had a pair of grey wedges sprouting from either side.

This was the UK’s latest look at the Konix Multi System, a console that promised to be, in the words of its makers, “the ultimate games machine.” It would offer multiple control options, games that loaded from 3.5-inch discs (far more affordable than cartridges) and graphics that could surpass the most popular current-gen computers of the day, the Amiga and Atari ST.

Back then, the Amiga and ST were about as close as you could get to recreating the colour and excitement of an arcade game in your bedroom. Certainly, their visual and sound capabilities were far beyond their older counterparts, the Commodore 64 and ZX Spectrum. That the Multisystem claimed to throw graphics around more quickly than either system – or even the then-powerful Acorn Archimedes – was a pretty big deal at the time. Better yet, it meant that the console could theoretically offer experiences that rivalled the most hectic games then available in arcades.

At the time, Afterburner was a good example of a popular game of the mid-80s period. Billed as a “full body experience” by its creator Sega, it offered the kind of custom-built exhilaration that you simply couldn’t get anywhere else. It featured a sit-down cabinet that buffeted and rocked the player as they moved a fighter plane around the screen; at a time when the blockbuster movie Top Gun was still fresh in people’s minds, Afterburner made a generation of arcade-goers feel like an unspeakably cool fighter pilot. Even the most powerful computer or console couldn’t replicate the thrills of such a game in the average home. Or could it?

Enter Konix, a British company widely recognised at the time for its range of joysticks. In early 1988, it began work on the Multisystem – also known by the codename Project Slipstream – its ambitious entry into the console market. It sounded on paper like a gaming fanatic’s dream: powerful hardware designed from the ground up for running games, while its use of floppy discs would have made those games far cheaper than cartridge-based systems from Sega or Nintendo. (It’s worth noting, too, that Sega and Nintendo’s 16-bit consoles didn’t hit the UK until the early 90s.)

Then there was the Multisystem’s unique case, which integrated the transforming joystick design outlined above. The aircraft-style yoke would be ideal for playing flight simulators (or an arcade flying game like Afterburner) but could also be turned into a steering wheel by adding a couple of extra pieces of curved plastic. Further, the yoke could be folded flat and opened out to resemble a pair of handlebars – perfect for simulating the control of a motorcycle. To make games even more exciting, the joystick would judder to simulate G-forces or crashes – a feature that wouldn’t become standard on console controllers until the late 1990s.

A switch on the side of the Multisystem could be flipped back and forth to simulate a gear lever, while a separate set of pedals could either be set at the front of the console, if it was sitting on a desk, or detached and placed on the floor to be used as a brake and accelerator.

It was a bold-looking, ingenious design that wasn’t like anything else on the market at the time. While there were all kinds of separate joysticks and controllers for different kinds of game – steering wheels for racers, yokes for flight simulators – none was as versatile as the Multisystem. And none had 16-bit hardware tucked away inside them.

Most excitingly of all, Konix wanted to sell the Multisystem for around £200 – a remarkably low price for the time, given that a printer or monitor could set you back around the same sum in the late 80s. An Amiga, meanwhile, would have cost nearer the £400 mark

Konix’s ambitions didn’t end there, either. A separate, hydraulic Power Chair was planned, which would have connected to the Multisystem to create a “full body experience” very like that offered by Afterburner in arcades. It was huge – far too big for the average teenager’s bedroom – but a tantalising prospect all the same. Other peripherals planned for the Multisystem included a lightgun and a joystick called the Navigator which, with its trigger, pistol-grip styling and top-mounted joystick, looks to modern eyes like a forerunner to the revolutionary controller shipped with Nintendo’s N64 console.

The Multisystem was, in short, truly ahead of its time – even if the promotional videos used to drum up interest were truly a product of the late 1980s:

As you can see, the Multisystem was largely geared up for arcade-style experiences like racing and flying games. It’s not clear whether the titles shown off above were intended for release or whether they were simply mock-ups – the relatively crude graphics appear to indicate the latter.

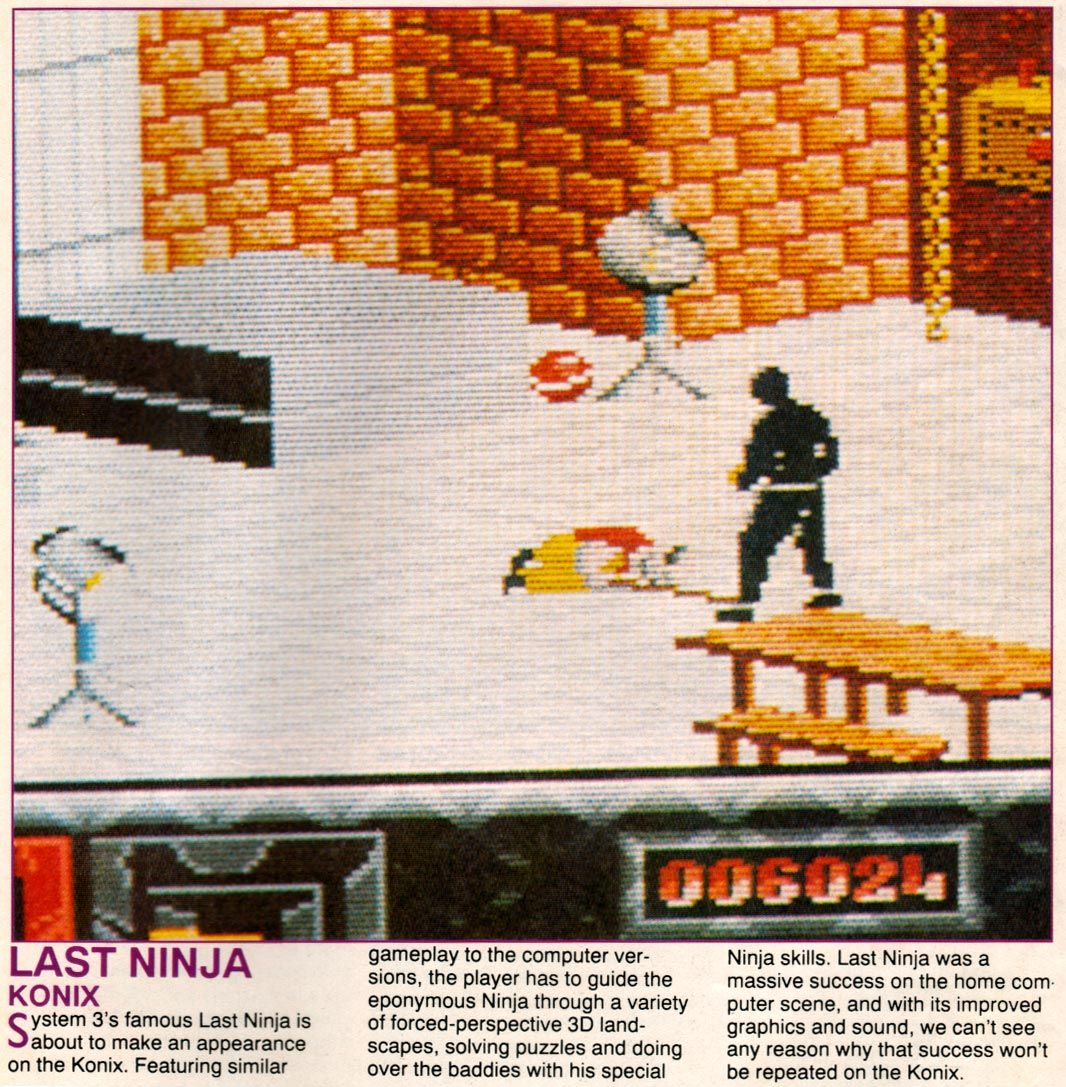

Another video shows off the Multisystem’s ability to throw around polygon graphics, which again, where impressive for the era. Beyond fancy demos, though, a number of popular games from the period were in development for Konix’s work-in-progress, including the isometric action game Last Ninja 2, 2D action platformer Hammerfist, and Jeff Minter’s quirky shooter, Attack Of The Mutant Camels.

Admittedly, those aren’t the kinds of smash hits that Nintendo and Sega could use to flog their consoles – no Afterburner, Sonic, Mario or Zelda here – which may have been the Multisystem’s stumbling block in the longer term. All the same, the console was clearly easy to develop for, because a wealth of games were apparently tested out on its hardware: James Pond II: Robocod was reportedly up and running, as was Ocean’s home port of the cutesy platformer, The NewZealand Story. Had the Multisystem enjoyed a decent launch, it seems likely that several European publishers – including Gremlin and Psygnosis – would have leant their support for the system.

By the spring of 1989, when that March edition of Ace Magazine was published, the Multisystem was primed for release, with its launch set for August that year. The console’s designer, Konix’s Wyn Holloway, described the response from the wider games industry as “enormous”; one German distributor pre-ordered 100,000 units to sell in that territory, while major publishing companies like US Gold pledged their support for the console.

“Our production capacity for the first year is already oversubscribed,” Holloway told Ace, “so we have to limit the launch to the UK and Europe in the first instance, to make sure we can keep pace with the demand.”

Sadly, it wasn’t to be. Despite the considerable media and industry interest in the Multi System – Holloway has even stated in an interview that Lucasfilm was interested in the machine – the console never saw release. By March 1990, the Multisystem still hadn’t appeared, and with The Games Machine magazine reporting that Konix had sold the rights to its range of joysticks, it was clear the company had serious cash flow problems.

In an interview with a website dedicated to the Konix Multisystem, Wyn Holloway suggested that the market simply wasn’t ready for the console. “When they don’t want it, they don’t want it,” Holloway said. “Our bankers just all of a sudden said, ‘No, we can’t support you anymore.’”

With plans for the console abandoned, the designs for the Multisystem were later sold to a Chinese manufacturer, which released it as a controller for the PC – a far cry from the innovative, multi-functional console Konix had originally envisaged.

For the gamers who’d pored over details of the machine in magazines through the latter part of the 1980s, the Multisystem took on an almost mythical aura, like the videogaming equivalent of a mirage: enticing, full of potential, yet always frustratingly out of reach.

You can read about the Konix Multisystem in more depth here.