Dr. Cyclops and the Cinema of Blindness

1940’s Dr. Cyclops puts today’s earnest, heartfelt, and super-powered blind characters to shame.

With the unexpected and newfound popularity of horror, sci-fi, and fantasy films at the beginning of the 1930s, the special effects departments at the major studios had their work cut out for them. Plundering innovations created by the makers of experimental and trick films from previous decades, they introduced mainstream audiences to extravagant monster makeups, onscreen physical transformations, invisibility, and pushed the limits of stop-motion animation. In James Whales 1935 Bride of Frankenstein and Tod Browning’s The Devil-Doll from a year later, it was proven that through a simple bit of celluloid sleight of hand, miniature humans could believably interact with normal-sized characters onscreen.

Hence in 1940, Paramount decided to make the latter effect the operative gimmick of their new mad scientist picture, Dr. Cyclops, and brought in Ernest B. Schoedsack to direct. While some have speculated Schoedsack was the optimal choice given that, at six-foot-seven, he understood a little something about being a giant among puny humans, the much more likely reason for the choice was that Schoedsack already had experience with films dealing in notable size contrasts, namely King Kong and its sequel, Son of Kong.

Another unusually tall man, Albert Dekker, a respected character actor who had previously appeared in 1939’s one-two punch of Beau Geste and The Man in the Iron Mask, made his horror debut starring as Dr. Alexander Thorkel, who is described by other characters at several points throughout the film as “the most brilliant biologist on earth.” When a former student stumbles across a massive deposit of radium in the Amazon, he summons Thorkel, believing his mentor would recognize it as a huge boon to medical treatment and research for doctors the world over. He also hopes Thorkel might set-up a state of the art research facility right there in the jungle to help care for the region’s poor.

Although Thorkel does indeed set-up a remote jungle lab, he has no interest in helping the poor or sharing the radium deposit with the rest of the medical community. Instead he keeps it all to himself to further his own unwholesome experiments, the nature of which remains a mystery for the film’s first half.

In the film’s opening scene, we get the exchange of a sentiment famously excised from the original Frankenstein, and one which seals Thorkel’s future downfall:

Dr. Thorkel: Are we then country doctors? You do not realize what we have here. In our very hands, we have the cosmic force of creation itself. In our very hands, we can shape life, take it apart, put it together again, mold it like putty.

Assistant: But what you are doing is mad! It is diabolic! You are tampering with powers reserved to God!

Dr. Thorkel: That is good. That is very good. That is just what I am doing!

Annoyed by his former student’s righteous impudence and refusal to help out around the lab, Thorkel kills the idealistic youngster, then sends off a cable, requesting three other noted scientists join him in the Amazon to become his new assistants. Only after they arrive do we learn the nature of Thorkel’s research.

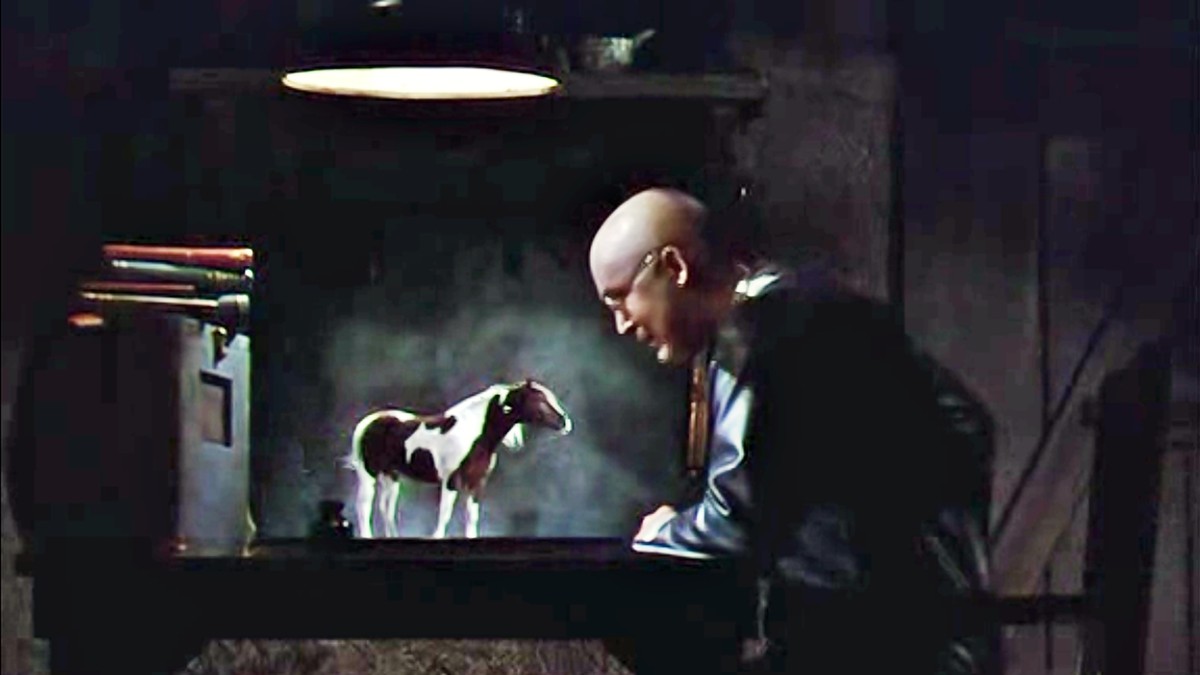

It seems the most brilliant biologist on earth has not exactly harnessed the cosmic power to create life, as he’d boasted to his first assistant. What he has done, however, is figured out a way to make existing life really, really small. Employing his new radium-powered shrink ray, he has created miniature chickens, dogs, pigs and horses, most of which are quickly gobbled up by his normal-sized cat. The script never clarifies what Thorkel’s larger intentions are, what he hopes to achieve by doing this, or what about his earlier research had led him to be considered the most brilliant biologist on earth. These are all things we must merely take on faith.

When his new would-be assistants sneak into his lab, read his notebooks, and are as righteously mortified as his first assistant had been, he tricks them all (as well as his Mexican houseboy and a prospector who’s tagged along) into standing under his shrink ray. Then he miniaturizes the lot of them.

For the second half of the film’s brief 77-minute run time, Dr. Cyclops becomes an effects-heavy adventure yarn as the now foot-tall scientists adjust to life in an oversized world while trying to avoid a now-gigantic mad scientist and his cat. But none of that matters. With the exception of Dekker, the acting is pedestrian teetering on the edge of amateurish, and the predictable script is stiff and clunky. If remembered at all today, which it rarely is, Dr. Cyclops is recalled for two things. Although not on a par with what Jack Arnold was able to accomplish 17 years later with The Incredible Shrinking Man, for its day Dr. Cyclops’ effects were quite impressive, which seems to be what most viewers take away. The film is also regularly, if erroneously, cited as the first horror film to be shot in early three-color Technicolor, though it came along about eight years too late to lay claim to that title, Warner Brothers’ Doctor X having beaten them to the punch.

But there’s something else going on here, a small unlikely plot twist and a grand joke that seems to escape most viewers; together they make Schoedsack’s little genre picture stand out.

When Thorkel summons his three new replacement assistants, we follow their arduous 10 thousand-mile journey (via a five-minute montage) from making arrangements in America to venturing deep into the Amazon jungle and up a rugged mountain range. When they at last arrive at the secluded lab, Thorkel informs his weary and hungry new guests he needs their help because he is going blind and can no longer use a microscope. He asks them each in turn to look at a specimen through the microscope and describe what they see. When they do, he is satisfied with their responses, thanks them for their help, and tells them they can go back home now. That was it, that was all he was asking for—just 10 seconds out of their day.

After that things become fairly pedestrian in genre terms, but it’s a brilliantly, unexpectedly, and perhaps inadvertently funny sequence, reminiscent of something you might encounter in a Tex Avery cartoon. What’s more, it hints at an even larger, if unstated joke. Namely, mad or otherwise, why would a scientist who was going blind decide his life’s mission involved coming up with a way to make things really, really small? Once he did, he’d never be able to find them again!

As an often frustrated blind cinephile, I am admittedly a bit obsessed with cinematic portrayals of the blind. Most I find infuriating.

In large part, cinematic blindos tend to be sickeningly noble sorts, and most have superpowers of one kind or another. Blind sidewalk pencil vendors always make the most perfect police informers, capable of describing a suspect’s height, weight, education, manner of dress, social standing, occupation and shoe size after a single 15-second encounter. Others are masters of the martial arts, capable of dodging speeding bullets and striking a villain’s pressure points via smell alone. Fucking Al Pacino can dance a perfect tango in an unfamiliar restaurant without tripping over a single chair.

In short most blind characters in movies make me want to tear my teeth out.

I’ve long held that Charles Sellon’s performance as Mr. Muckle in W.C. Fields’ It’s a Gift (1934) remains perhaps the most accurate and honest depiction of blindness onscreen. I can now add Dekker’s turn as the diabolical Dr. Thorkel to the list, for that one scene alone.

As a blind man, I am confronted on a daily basis with small, insignificant tasks that require sight, so in my case require a little assistance, often from strangers. (“Which of these is the sharp cheddar?”). Most are happy to take that 10 seconds to help out. Once they do, I thank them and let them go on with their day, feeling better about themselves for having helped out the disabled. So what the hell’s wrong with these asshole scientists? A blind colleague, the most brilliant biologist on earth, asks for a tiny bit of help—a quick glance through a microscope to confirm something—then thanks them cordially and sends them on their way. Instead of being gracious about it, instead of feeling good about themselves for having helped out a respected colleague in need, what do they do? They throw a little hissy fit, they refuse to leave, and then set about invading Thorkel’s privacy! What a bunch of smug assholes.

I’m sorry, maybe I read the film differently than most, but diabolic as he may be, my sympathies are fully with Thorkel here. I mean, let’s see any of these other righteous blowhards come up with a radium-powered shrink ray after realizing they were going blind. I bet they couldn’t. Nope, you ask me they deserved far worse than they got.

I also have the deepest respect for Schoedsack and screenwriter Tom Kilpatrick for having the courage to present audiences with an honest portrayal of a blind character who is not only not noble, but a mad scientist to boot. There is so much untapped potential there, the makings of an entire comedy series (“Say, could you help me a moment? I can’t seem to find the ‘on’ switch for my death ray, here.”)

Well, I’ll need to think about that one awhile.

In any case, Schoedsack would not direct another film for nine years, until returning to his bread and butter and re-teaming with Willis O’Brien for Mighty Joe Young. Dekker, meanwhile, continued with what would be a very prolific career as a character actor, including a notable turn as the mob boss in The Killers (1946). Apart from an appearance in an episode of Lights Out, he would never appear in another sci-fi, horror, or fantasy film. Yet ironically enough, at the time of his death, Dr. Cyclops would remain, much to his dismay, Dekker’s best-remembered role. The film itself, minus the blind angle, would go on to inspire the mid-1970s live-action Saturday morning weirdie, Dr. Shrinker, co-starring the great Billy Barty.