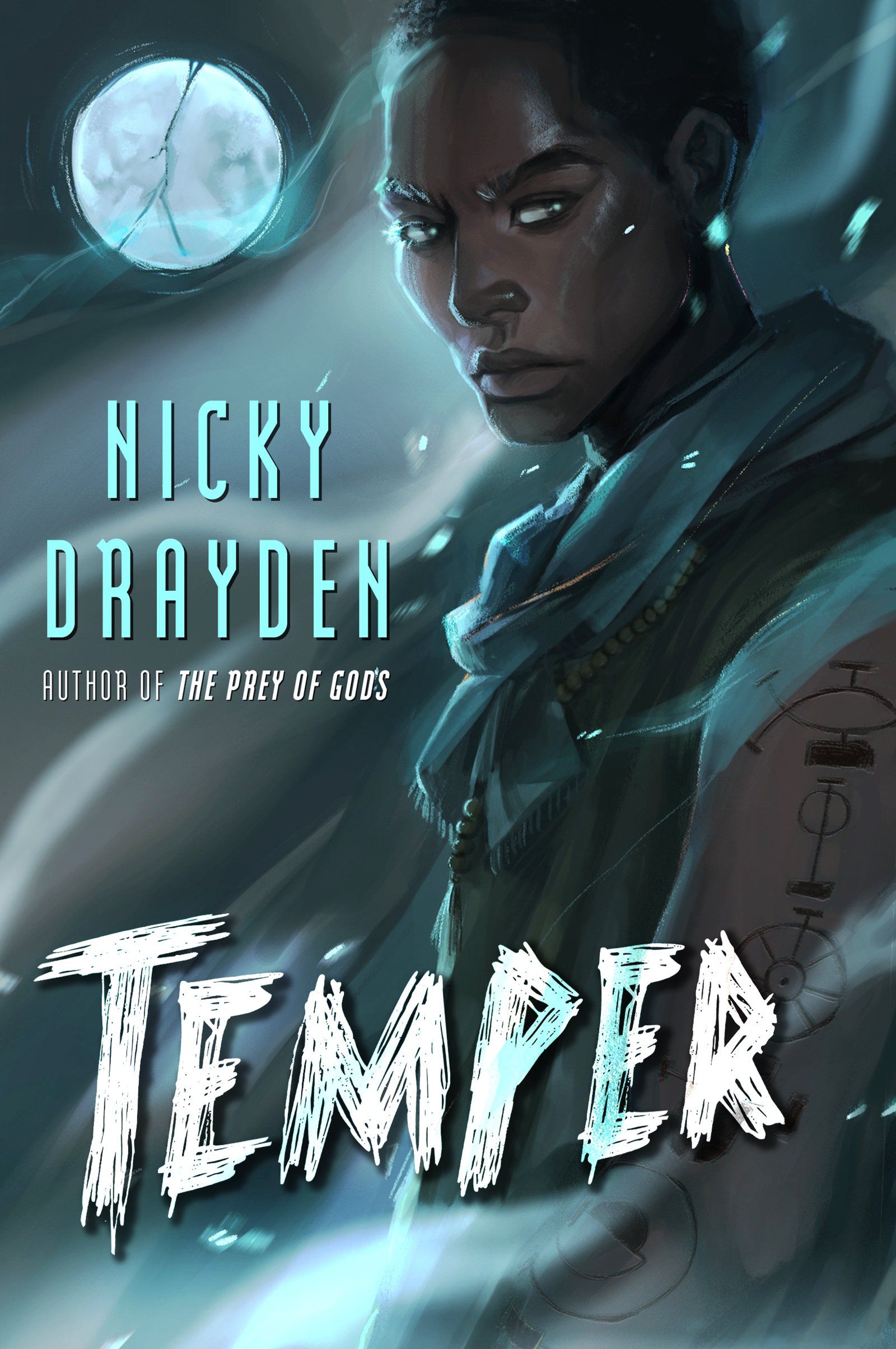

Temper by Nicky Drayden Review

Nicky Drayden's genre-defying speculative fiction novel imagines an African society structured around twins.

Imagine a world in which most people are born twins. Imagine that, between these sets of twins, seven vices and virtues are split. The twin with the most virtues goes on to live in the upper echelons of societies. The twin with the most vices is known as the “lesser twin” and, though some rise to the level of middle management, some never make it out of the slums known as “the comfy.” Furthermore, if a twin is too geographically far away, they suffer from a proximity break: physical pain at the absence of their missing half.

This is the fascinating world that Temper: A Novel‘s Auben and Kasim are born into. The teen characters in the speculative fiction narrative from Nicky Drayden (The Prey of Gods) are a six and one pair, which means Kasim has nearly every virtue, and Auben revels in having nearly every vice.

Read Temper by Nicky Drayden

Protagonist Auben embraces his bad boy image, indulges in his lechery and duplicity (among his favorites of the vices). But, lately, stretches on proximity have been harder for him to manage, and to make matters worse, he’s hearing voices in his head urging him to darker acts. It scares him and, in order to solve the problem, he’s willing to risk relying on magic to let him go, on his own, to Grace Mountain, where he can ask Grace, the god of the virtues, for help. Instead, he comes face to face with Grace’s twin, Icy Blue, a demon who needs human blood to survive—and who takes Auben’s body as his host.

A nuanced world…

As is the case with most frequent readers, I seldom read a book for which I can’t see the shape of the plot early on, but Drayden turns enough corners with the plot that she manages to offer surprises, even in the final chapters. Because of that, this review won’t dwell too much on plot details, so that you can be as delighted as I was by the surprises in store.

Temper feels like it’s going to become a horror story about a third of the way through the book, but the story plays with horror tropes only to transcend them, building instead into a commentary on faith, marginalization, and disconnection from fellow humans, with a healthy dose of sibling rivalry—and love—in the mix.

Part of the reason the shape of the plot is so well hidden from the reader is because Drayden lavishes such loving devotion into building her setting, with all its flaws, keeping the reader fascinated and distracted by the richly-realized alternate world. Geographically resembling Cape Town, South Africa, the primary setting of the novel is Greater Bezile, Mzansi, a city at the base of Grace Mountain, and thus the home of Mzansi’s dominant religion.

Auben and Kasim come from “the comfy”—slums populated dominantly by lesser twins, set aside from the nicer areas of the city by a wall, but still close enough to their more fortunate twins that they won’t suffer proximity breaks. When Auben is trying to convince some girls to come home with him and Kasim, Drayden uses it as an opportunity to describe the stereotypes of the district, followed by Auben’s thoughts in his point-of-view narration:

‘Can you promise we’ll see wu mystics and holler whorse, and eat mealie pap and fried chicken feet, and wash it all down with a heavy quart of tinibru?’ Her tongue is sharp and accurate, but I don’t take offense. Sometimes stereotypes are stereotypes for a reason.

Beyond “the comfy” are the nicer parts of town where Auben and Kasim’s mother lives. She and her husband have another pair of twins, of age with Auben and Kasim. They are gender chimaeras called kigens. Kigens make up nearly half the land’s population.

Chimwe and Chiso are a feminized male (fem kigen) and a masculinized female (andy kigen), respectively. While some kigen present more one way than the other, Chimwe and Chiso are nearly identical. Drayden uses “ey” and “eir” as an alternate pronoun structure throughout, and kigen characters appear throughout the story in different roles, emphasizing the prominence of the gender chimaera population.

But, despite their prevalence in the population, kigen are marginalized, and their gender slurs are established early on to give readers an idea of the hurdles that kigen—especially kigen who are lesser twins—must overcome.

Religion and equality…

Beyond the city and nation lies a wider world, full of cultures that judge Mzansi customs and religion as archaic. There are Mzansi who agree with this outside perspective, but those pro-science subsecularists are persecuted even more than singletons (the culture’s term for people born without a twin).

Auben’s Uncle Pabio, who is fond of conspiracies, posits:

[Grace and Icy Blue] are just clever inventions for branding morality, and that schools… were designed to separate us from nature, from our tribal communities and cultures, and from critical thinking so that we could wholly tolerate this unjust and unnatural system instituted by a bunch of wealthy Nri immigrants fearful of growing Nationalism and the Mzansi elite who pulled their strings…

Sometimes I want to believe him, to think he knows something that the rest of us don’t, but then he’ll start ranting about ‘death traders’ skimming around the ocean in their sailing ships, and their ‘skin the color of sun-bleached bone’ and how centuries ago, they ‘almost nearly could have brought an end to the Nri empire spread out along the west coast of the continent and the Ottoman empire on the east, and all the lands like ours caught inbetween’ and it all just gets to be a bit much to swallow.

That’s as much explicit commentary as colonialism gets in the narrative, but the laying out of Mzansi’s entire social structure makes sure the reader is well aware of who has the power and who doesn’t, while the narrative plays with ways to create equality for those who are oppressed. And, while I’m not sure I agree with Drayden’s ultimate treatment of vice without virtue (and vice versa), the ideas she plays with while doing so make the whole question of good and evil, when it comes to humans, one well worth considering.

While there are characters throughout the novel who blame religion for all the world’s shortcomings, Auben and Kasim’s connection to those larger powers never allow for a simple answer to the world’s flaws. The way that Drayden uses explorations of morality and mythology through the narration of a teenage boy—whose coming-of-age, given that it involves demons and divinity—is far more complicated than most, is artfully done, woven into a story that may keep you awake at night, wondering where it’s headed next.

Temper is now avaiable to purchase via Amazon or your local independent bookstore.