Kings of a Dead World: Why We Tell Sleep Dystopia Stories in an Age of Climate Change

Lullaby or nightmare? Author Jamie Mollart on whether insomnia or inception can solve the world’s problems, or just make things worse.

This piece is sponsored by

Author Jamie Mollart laughs while admitting this, but the idea for Kings of a Dead World, his new dystopian novel about a world put to sleep to conserve resources, came to him in a dream. And why shouldn’t it have? “Sleep on it” is the common advice for a human being pondering a big choice or change, with the promise that a good night’s sleep will allow them better perspective to write a novel, make a life-shifting decision… maybe even save the world?

Over fifty years ago in Welcome to the Monkey House, Kurt Vonnegut vividly described a grossly overpopulated Earth like the tightly-packed drupelets of a raspberry. Mollart’s bleak near-future bears these familiar hallmarks, further complicating overpopulation with rising water levels, dwindling fossil fuels, and, most damningly, individual countries’ failure to halt the global climate crisis on their own terms. The solution, then, requires a global sacrifice: The majority of the world’s population spends three months in a chemically-induced, coma-like Sleep, with one month Awake in which they make up for that lost time. Everyone, that is, except for the Janitors, who live by natural circadian rhythms: monitoring the Sleepers’ vitals, as well as conducting worldwide Trade to deliver Creds into their accounts so that they have some earnings to spend in their limited Waking hours.

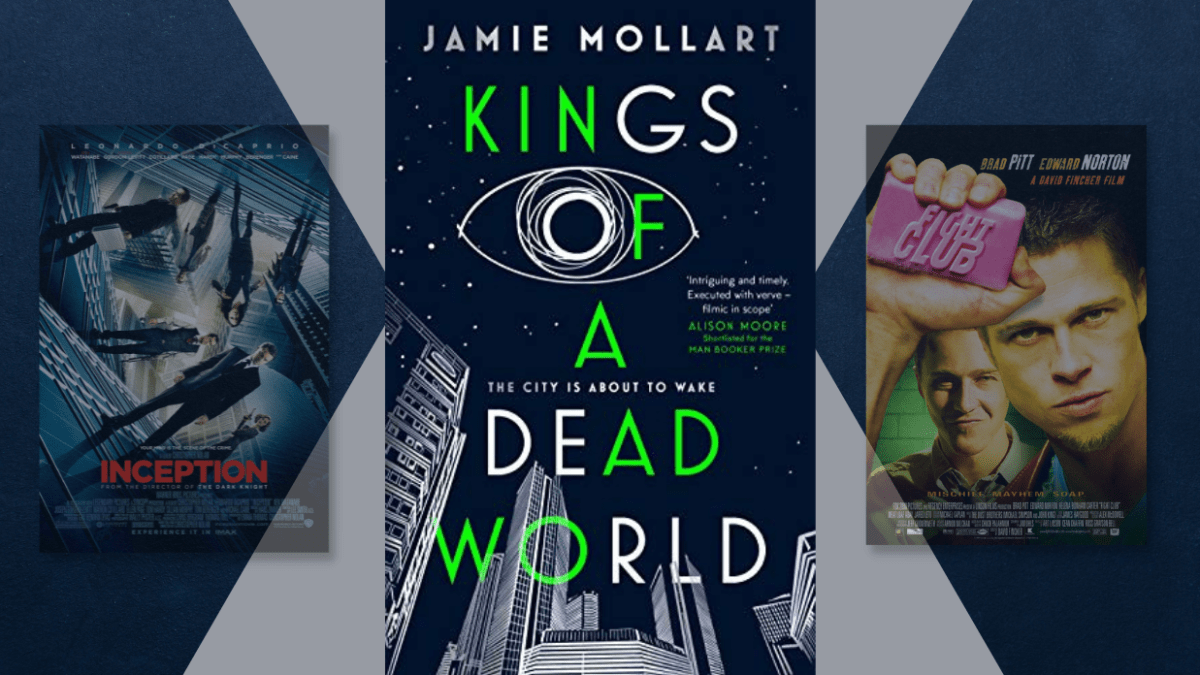

As a way to curb consumption, it makes sense in theory, and has Kings of a Dead World joining a subgenre of dystopian or otherwise speculative fiction in which sleep can potentially solve seemingly insurmountable societal problems: David Fincher’s seminal film Fight Club, Karen Russell’s quietly devastating novella Sleep Donation, Christopher Nolan’s dreamlike Inception, and so forth. After all, there’s something incredibly alluring about the idea of closing your eyes and trusting that the world will fix itself while you snooze. It’s the same passive self-improvement your body undergoes during the normal stages of sleep, but on a colossal, collective scale: the ozone layer restitches itself, the stocks go up, the Earth gets a break from billions of footprints. It’s almost like rewinding time.

But that’s the thing, Mollart says, when Den of Geek speaks to him about his new book: “Time’s like a false constraint, isn’t it? You’ve got the sun coming up, the sun coming down—there is an obvious set of divisions of how people spend their time. But the whole hour and minute thing—we’ve made these false constraints that we as society have put onto things. It’s humans grappling with what’s in front of them in nature, isn’t it? It’s this whole thing we can’t control, so we try to control it by putting our own constraints on it.”

False or not, these societal constraints have created an inverse relationship between sleepers and wakers, their movements balanced by time zones that dictate when half of the world ends the day while the other half is just beginning. In fiction, this dynamic is even more pronounced, with characters moving through the dream realm at cross-purposes to one another, whether it’s the Inception team planting ideas three layers into the slumbering subconscious, or Tyler Durden puppeting the Narrator’s body for cross-country flights to found Fight Clubs all over the country. Kings of a Dead World alternates between the perspectives of Ben, an octogenarian whose age belies his revolutionary fighting spirit, struggling to take care of his sick wife Rose during their brief time Awake; and Peruzzi, a Janitor who has the Sleeping world as his playground yet suffers an existential lack of purpose.

Being the sleeper is easy, or so we think: Sleep Donation posits that donating sleep is as painless and noble as giving blood. That’s the party line for the Sleep Corps’ champ recruiter Trish Edgewater, who convinces the parents of newborn donor Baby A that she has a surfeit of the stuff, and to not give would be to doom the nation’s insomniacs to an agonizing, brutal, unnecessary death. For Baby A, or Washington Irving’s archetypal snoozer Rip Van Winkle, or the Narrator, they get to wake up into a changed world. It’s the people watching them sleep, moving through the insomniac hours, who have to do the actual hard work of breaking and reshaping the world.

In the Narrator’s case, Mollart says, “[he] can’t break out of the cycle that he’s in without inventing someone to tell him how to do it, which is just such a modern male thing. We’re rubbish about talking about our feelings; we’re rubbish about facing responsibility for ourselves.” Toxic masculinity is a recurring theme in Mollart’s work, from his prior novel The Zoo to his next project: “We’re the shit half of the species, and I just think male friendships are really interesting. Most blokes have one real strong relationship, often from your childhood, and you become really mirrors of each other. That’s kind of what the Tyler Durden/Narrator [dynamic] is like. Blokes egg each other on, [and] it’s difficult for men to show affection to other men, it’s just sad. As long as that continues, we won’t break the cycle of nonsense of male violence and the patriarchy that we’ve got unfortunately still.”

The Tyler/Narrator dynamic plays out in the relationship between fellow Janitors Peruzzi and Slattery: colleagues, quasi-friends, and partners in crime. While their decadent lifestyles spoil them with at-home gyms and Brave New World-inspired raves every three months, Slattery tempts Peruzzi into seeking out greater highs than pills and sex. Their explorations into the Sleeping world at first tap into a Fight Club-esque awakening of the blood, only to tip into Project Mayhem levels of voyeurism and violation in pursuit of confirmation that what they do actually matters.

Despite these outbursts, the Janitors remain a shadowy presence in the lives of the Sleepers, watching them but not motivating them to Sleep. That incentivization comes from this world’s new-old religious order: the chronological trinity of Chronos, Bacchus, and Rip Van. “In a world where you hit a cultural stop,” Mollart explains, “where it goes from this to this, it felt to me that you would go back to something quite primal.” He turned to ancient mythology for the personification of time (who oversees the Sleep/Wake cycles) and the god of partying (who rewards the Janitors for their hard work). But it was fairy tales that provided a folkloric Jesus Christ figure for the Sleepers in Rip Van, a figure who every extended Sleep cycle seems to preach, I did it, and you can too. I lost twenty years, you can give up three months.

Fairy tales, Mollart said, are “rooted in innate primal fears; they’re very much about things we worry about on a hunter-gatherer level, like getting lost in woods [and] wicked witches turning us into things. They’re very dark, aren’t they, but with this playful exterior.” His description sounds not unlike dreaming, in which the dreamer uses that otherworldly space to process waking events and subconscious conflicts.

But what about a Sleep with no dreams? “I wanted there to be a difference between forced Sleep and actual sleep,” Mollart says. “It shouldn’t be a thing where you get to restore your body and your mind. It’s like they’re turned off, literally turned off.”

Although the Sleep is initially presented as a solution for the sake of the common good, it becomes clear that it is more of a life sentence than a sacrifice. “It’s the actual stealing of time,” Mollart says, “time is stolen from them, rather than time you can do something else in. If they were having beautiful dreams while they’re Asleep, it would just take away a little bit of the fear of it. … There should be nothing. Not to get into the comparison with death and all that, but it’s little incremental bits of death.”

This is especially the case for Ben’s wife Rose, afflicted with an unnamed disease suggestive of dementia, in which she Awakes into different eras of her life. Because Ben never knows which Rose will Awake, or how panicked she will be—with any heightened stress levels forcibly putting her back to Sleep—their time together is so precious. Mollart likens it to currency, especially with Peruzzi as the have to Ben’s have-not: “He’s got so much time, but he doesn’t do anything with it, whereas Ben is the sort of person who’s working really hard to look after their family, and every penny counts. When you’ve got loads of something, you lose a sense of what it’s worth.”

Ben’s struggles to reach Rose mirror that of Inception’s Dom Cobb, who even in other people’s dreams is haunted by his subconscious’ projection of his dead wife Mal. He blames himself for getting her so immersed in dream-sharing that, despite living fifty years in the space of a dream, she believed upon waking up that she was still dreaming. That conviction, that she was stuck in a waking dream, led to her suicide. For Rose, some months she emerges having gone through fifty years of Sleeping and Waking with Ben; others, she’s young and scared and doesn’t understand why her body is being turned on and off like a light switch.

Despite being a universal aspect of the human body, sleep itself is such an intensely individualistic experience. Even if interlopers can infiltrate dreams in Inception, or if a nightmare can taint a sleep supply like in Sleep Donation, a given night’s sleep still feels like it is intimately owned by that person. This quandary mirrors our society’s approach to the climate crisis: “One of the whole problems with climate change is it’s just too big, you can’t picture it,” Mollart says. “It’s so big that you can’t understand that recycling more or not eating meat or not using single-use plastic will have a difference, because the problem’s too big. I think it’s that sort of mentality, that we can only project so far out from ourselves; and I think when you’ve had things taken off you, you very quickly resort to looking after yourself and those close to you. It’s human nature—not very nice human nature, but that we all do.”

Trish promises the Harkonnens that the Sleep Corps will not overdraw Baby A’s sleep supply, painfully aware that she’s saying so “at a moment when people are plunging their straws into every available centimeter of shale and water, every crude oil and uranium and mineral well on earth, with an indiscriminate and borderless appetite.” When sleep becomes yet another resource to be exhausted, Russell shows readers, the individual will be exploited supposedly for the greater good, in reality robbing the next generation of their future.

“Our fathers were our models for God,” Tyler tells the Narrator while branding his hand with lye. “If our fathers bailed, what does that tell you about God?” While Kings of a Dead World unpacks toxic masculinity, it contextualizes that misbehavior within this greater trauma of parental abandonment and explores how to break the aforementioned cycles of violence caused by a refusal to engage with one’s feelings.

Outside of fiction, that’s witnessing our planet’s youngest generation openly speak out about being burdened with an irreversibly damaged world with a shrug in place of an apology. Their unfortunate position fits the second half of that oft-quoted Fight Club monologue: “You have to consider the possibility that God does not like you. He never wanted you. In all probability, he hates you. This is not the worst thing that can happen.” By acknowledging their shit situation instead of trying to ignore it, the next generation is trying to find a way forward.

Despite Kings of a Dead World being more of a cautionary tale for mass sleep, Mollart acknowledges that, on an individual level, sleep can certainly be a positive force for change.

“It actually is in Fight Club, isn’t it?” Mollart says. “In a very messed-up kind of way. The whole bringing down of society happens because the sleeping version of him is more proactive than the waking version—and he goes about things in a very fucked-up way, but his intentions are good. The ending scene with Pixies’ ‘Where Is My Mind?’, where all the [credit card companies] get blown up, is supposed to be a positive, uplifting ending. It’s like he’s dreamt—well he has dreamt the whole thing, weirdly—and then he wakes up and it’s this fresh start. He’s got rid of his demons, he’s with Marla, and their society’s monetary evils have been wiped out.”

That distinction between sleep and waking is crucial. Dystopian sleep stories are not meant to be soothing lullabies, especially when threaded with narratives about climate change. They are meant to depict the nightmarish future that cannot be pushed off—not by escaping into symbolic dreams, not by punting the issue to children and grandchildren. Sleep should be utilized for its initial purpose of recharging—but at some point we have to complete the cycle by waking up.

Kings of a Dead World is available June 10 in the UK from Sandstone Press. Check out the full synopsis below…

The Earth’s resources are dwindling. The solution is the Sleep.

Inside a hibernating city, Ben struggles with his limited waking time and the disease stealing his wife from him. Watching over the sleepers, lonely Peruzzi craves the family he never knew.

Everywhere, dissatisfaction is growing.

The city is about to wake.