Where Andy Kaufman Came From

Genius that he was, Andy Kaufman may not have been a complete original.

Following the release of the 1999 biopic Man on the Moon — which was itself accompanied by a slew of new biographies, video collections, and a soundtrack written by R.E.M. — Andy Kaufman was suddenly a household name again, cited repeatedly as a wildly innovative comic genius like no other. In a blink everyone loved and admired that Andy Kaufman. To this day Kaufman books, graphic novels and documentaries (like the recent Jim and Andy) continue to come out.

But people had forgotten a few things. First, in the intervening 15 years between his 1984 death and the release of the Milos Forman film, Kaufman had been all but completely forgotten, and those who did remember him only remembered him as that cute and lovable Latka Gravas on Taxi. People also forget that over the course of his decade-long career in the public eye, Kaufman had quite consciously and successfully established himself as one of the most despised figures in show business.

In the 1970s, Kaufman began performing a routine both on and off stage that baffled and enraged audiences. Was it even comedy? The Foreign Man thing was funny, but what was this wrestling women nonsense? And reading The Great Gatsby aloud? That’s not funny at all! He was soon besieged with death threats and banned from SNL. Even his transcendental meditation guru banished him, which takes some doing.

I don’t recall where I first saw him, but it was a few years before Taxi premiered in 1978. It was likely one of his appearances on Saturday Night Live or the late-night talk shows. Wherever it was, very early on I became fixated on this strange little comedian whose act wasn’t exactly funny in the traditional sense. He didn’t tell jokes or offer pithy social observations. When you get right down to it, apart from a few one-off bits here and there, he only had a small handful of actual comedy routines he performed over and over again throughout his career, like Mighty Mouse, Foreign Man and the Caspian Harvest Song.

The rest was performance art, and that’s what started pissing people off no end. He’d go on Letterman not to tell jokes or do his Foreign Man thing, but to beg for money, explaining he was destitute. Or he’d bring his parents on the show with him for no other reason than to publicly apologize for being such trouble when he was a kid, and to tell them how much he loved them. Or he’d wrestle women. The majority of his act was consciously designed to make audiences (and talk show hosts) as uncomfortable as possible. The more he pushed it (inviting audience members to come up on stage and pay a dollar to touch the boil on his neck), the more he pissed people off and the more obsessed I became.

Now there’s no damn point in my delving into the weird details of Kaufman’s life and career. That’s all out there. And there’s little point in describing his act, the emergence of his alter ego, boorish nightclub entertainer Tony Clifton, or the role of Bob Zmuda, Kaufman’s writing partner, standard audience plant, part-time Tony Clifton and official heckler. Instead, love and admire his work as I do, I just want to point out something that’s remained buried all these years (and it’s not his film career): Namely, it could be argued Kaufman lifted pretty much everything he did from Dick Shawn.

Today Shawn has been sadly forgotten save for two film roles: as Ethel Merman’s dippy beach bum mama’s boy son in It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World, and as LSD in Mel Brooks’ The Producers.

As a stand-up comedian, though, Shawn began performing in nightclubs in the mid-’50s around the same time as Lenny Bruce. Both men shattered the tight-assed suburban mores of the Eisenhower era, and both redefined what could be considered comedy. While Bruce pushed the limits of language and acceptable subject matter, Shawn blurred the line between comedy and performance art, long before most people knew what performance art” was.

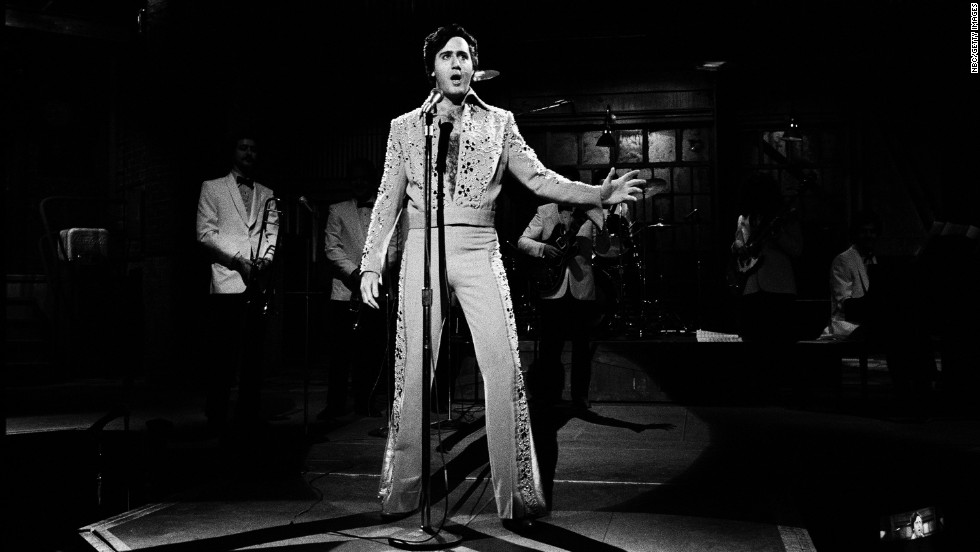

Shawn’s act, which over time evolved into a one-man show he called The Second Greatest Entertainer in the Whole Wide World, consisted of song and dance routines, sketches, pratfalls, impressions, and monologues. It sounds like any other variety show of the era. But as would be the case with Kaufman two decades later, nearly all his impressions were identical and identically awful. Long before Kaufman did exactly the same thing, Shawn would come out on stage and do his laundry or crawl into bed and go to sleep. The dance numbers, if not exactly dazzling, were at least, um, unique, and the pratfalls often came unexpectedly with no standard comedic payoff. The one thing Shawn never, ever did was tell jokes. His entire routine was calculated, yes, to make confused audiences very, very uncomfortable.

Audiences would enter the theater to see a stage that was bare except for a pile of bricks. Come the appointed time, Shawn (not a small man) would emerge from within the pile of bricks and get on with the show. During intermission, he would lay on his back center stage and not move until the second act was set to begin.

Still, as with Kaufman’s Foreign Man/Mighty Mouse routine, it was a popular enough act that Shawn became a talk show fixture in the ’60s and early ’70s, where he usually (like Kaufman) made a point of insulting the audience, the other guests, and the host. During a notorious appearance at a Friar’s Club roast for Cheech and Chong, Shawn stepped up to the podium and, instead of cracking more dirty jokes or tossing out more insults, vomited pea soup all over himself.

Despite it all he earned roles on Broadway and in films, though even then no one knew quite what to do with him. In early screen appearances like The Wizard of Baghdad or Wake Me When It’s Over, he was cast as a laid back hipster. Later he was reduced to smaller roles in lesser films and silly TV shows, usually playing oddballs of one kind or another.

But until the end he kept returning to his only true love— his one-man show. Again like Kaufman, he preferred to play to college audiences, explaining they would better understand what he was doing than audiences in Vegas or the Catskills.

Granted there were a number of things Andy did which were uniquely his own, like his later Letterman appearances, the bit with the boil, the wrestling women and the feud with Jerry Lawler, but there are parallels enough to be a little suspicious, and in a way they continued to the end.

When Kaufman was diagnosed with lung cancer, people assumed it was more of his shtick, even as he lost his hair and was confined to a wheelchair. Three years after Kaufman died, Shawn did him one better.

In April of 1987, Shawn was doing his Second Greatest Entertainer show at the University of California-San Diego when he dropped dead of a massive heart attack in the middle of a monologue. Given the nature of his show, the audience laughed and clapped. Worse, as he always did, Shawn had warned stagehands before the show not to come out on stage no matter what happened, because he was never sure himself what he was going to do. It took five minutes before everyone decided it had gone on a bit too long. A stagehand finally rolled him over and called for a doctor. Even after being told to clear the auditorium, the audience stayed put, convinced this was all part of the act. It wasn’t.

For once, the tables had been turned, as Kaufman had made the onstage death of an elderly guest part of his 1980 Carnegie Hall show. In Kaufman’s case there had also been an onstage resurrection. Shawn wasn’t so lucky.