The Batman: Can a Superhero Movie Be Too Dark?

The Batman proves again that with each new movie adaptation of The Dark Knight, you cannot get dark enough.

“What are you?” It’s a question posed to any self-respecting Batman in his first movie, and it’s one that always gets the same answer. “I’m Batman.” That’s the iconic bit Michael Keaton whispered in Batman (1989), and Christian Bale growled in Batman Begins (2005), each arriving in a movie that stunned audiences in its day. Yet those moments seem like child’s play when compared to Matt Reeves’ The Batman, a film that, despite only being 25 percent filmed, shocked fans during this weekend’s DC FanDome.

When Robert Pattinson’s Batman is asked “what the hell are you supposed to be?” he responds with a brutal, almost sadistic beating of the other party. Using the kind of violence that would be deemed excessive force if he were in blue instead of black, the Batman pummels the man into a puddle before gasping, almost to his own surprise, “I’m vengeance.”

This isn’t your father’s Batman. It isn’t even your Batman from five years ago.

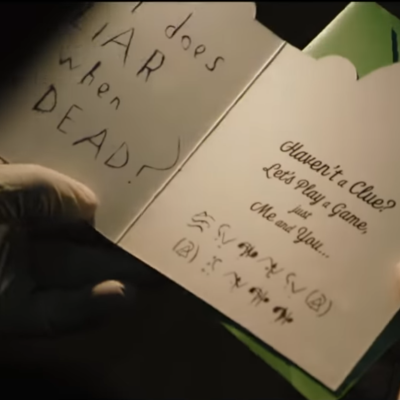

Like new iterations before it, Reeves and Pattinson’s interpretation of Bruce Wayne crawls deeper into the abyss and the crime dramas it emulates, finding something more grotesque and unsettling than we’ve previously known… which makes it irresistible to adult comic book fans. Whereas Christopher Nolan had grand success with his epic interpretation of Batman, pulling as much from the sweeping moviemaking of David Lean as he did the chilly criminality of Michael Mann’s Heat, Reeves appears to be diving into something decidedly grittier and more unsettling. The Riddler-based crime scene at the beginning of the trailer, where a riddle accompanies a presumably mutilated corpse, recalls the neo noir fatalism of David Fincher’s Seven.

In fact during the DC FanDome panel, Reeves outright named Roman Polanski’s Chinatown as his “key” cinematic inspiration. That 1974 classic is a detective thriller in the mold of other 1940s and ‘50s film noirs, but in Chinatown the tropes were liberated by ‘70s cynicism. Thus the movie depicts a Los Angeles rotten to its core, and far beyond redemption. The downbeat and defeatist ending even confirms there is no salvation for anyone.

While it’s still early goings for The Batman, it would appear the new movie is leaning into that sentiment, making the hopeful optimism of saving Gotham City at the heart of Nolan’s The Dark Knight Trilogy appear doomed, or at least naïve. Consider Reeves also said at the panel, “Where did Bruce’s family sit in that [citywide corruption]?” He’s teasing a third act revelation as crippling to Bruce’s belief in the system as the revelations that damned Jack Nicholson’s gumshoe and everyone he ever met in Chinatown.

But then that may be par for the course, with nearly every cinematic adaptation of Batman trying to justify its existence by being more ruthless, more sinister, and ultimately more cynical.

Treated as a beloved relic of ‘80s and ‘90s kids’ nostalgia today, when Tim Burton’s Batman opened in 1989, it stunned audiences with a black-clad superhero who brooded as much as he saved the day, and a performance by Jack Nicholson so nasty that his Joker was publicly dismissed by his predecessor, Caesar Romero. Keep in mind that in the late 1980s, Batman was still the subject of pop culture ridicule and camp thanks to Adam West’s 1960s television series, on which Romero played a harmless prankster in a purple suit.

Upon seeing Nicholson’s Joker, who killed people with a smile and electrocuted mobsters to death with a joy buzzer, Romero said Nicholson “was just so violent” and the movie was “dreary.”

Of course compared to Heath Ledger and Joaquin Phoenix’s Oscar winning portrayals of the Clown Prince of Crime, Nicholson looks camp himself. But this showcases the creeping need for adults to darken their Gotham heroes and villains. The generation of parents who grew up with Adam West would revolt against Tim Burton’s stylized noir aesthetic in Batman and even grimmer Gothic fairy tale in Batman Returns (1992), with some parents protesting the second movie specifically and McDonald’s association with it via Happy Meals.

“Violence-loving adults may enjoy this film,” lamented one angry letter from a parent to The Los Angeles Times. “But why on Earth is McDonald’s pushing this exploitative movie through the sales of its so-called ‘Happy Meals?’ Has McDonald’s no conscience?”

Following the parent backlash to Batman Returns, Warner Bros. momentarily conceded the point and hired Joel Schumacher to make a pair of toyetic and Happy Meal-friendly superhero movies. But when that vision fizzled out, Christopher Nolan stepped in to make his groundbreaking superhero trilogy.

The film that coined the term “reboot,” Batman Begins eschewed the fantastical excesses of the Burton and Schumacher years, and revealed a strong allergy to anything camp. Nolan’s films were intended to be big old school Hollywood epics, with each having its own specific inspirations. On the whole though, they offered standalone action dramas that defied modern convention with an emphasis on in-camera stunts and somber-to-a-fault characterizations. Bale’s Batman even went about his crime fighting with the exacting vision of a campaign strategist, seeking to turn his Dark Knight persona into a political platform that would inspire Gotham to save itself.

And his villains, in their various forms, were allegorical stand-ins for all the anxieties facing Americans in the early 21st century: foreign terrorists scheming in the mountains; the lone gunman who just wants to watch the world burn; and a populist demagogue who would drag our institutions to collapse. That last one is eerily prophetic these days. At the time, however, it was all in service of an entertainment spectacle as big as James Bond or Michael Bay, but now filmed in dazzling IMAX photography.

Heath Ledger’s Joker was terrifying to many, but he was also a beloved figure for his seemingly supernatural ability to know and undermine everyone’s motivations and to speak with a forked tongue as seductive as the Devil. Feeling like a real-life monster, he could be scary to adults, unlike Nicholson’s Joker, but he was still a rock star as far as internet memes were concerned.

In other words, a far cry from what came later in Phoenix’s lonely and visibly unpleasant murderer, Arthur Fleck. But before Joker or Pattinson as The Batman, we got a nominally darker Batman than Nolan’s. As portrayed by Ben Affleck in Zack Snyder’s Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, the Caped Crusader was now a deadened, self-righteous fascist who liked to prove his badassery by branding criminals with bat symbols and driving his Batmobile through someone’s skull. Nolan’s Gotham created the illusion of a grounded, grim reality, but Snyder’s was just grim: a humorless exercise in violence that appeals to a certain type of angsty teenage nerd. Nevertheless, Snyder recently insisted on Twitter that his vision of DC superheroes is “made for grownups.”

While I personally find the end result unconvincing in that regard, the desire for a more serious, “grownup” Batman is evident from Burton through Snyder, and now Reeves. Future generations who grew up with The Dark Knight Returns comics or Burton’s movies don’t feel the need to protest if a Batman movie isn’t made with Happy Meals in mind. In fact, they demand it—and revel when a Joker movie is so macabre and nihilistic that it creates misplaced anxiety about “These Times,” and wins Oscars for Best Actor and Best Original Score.

The results can be as exhilarating as The Dark Knight or as numbing as Batman v Superman, but both appear to benefit in appeal from fans who, after growing up with ostensibly serious versions of these characters, wanted to see that taken further into mature storytelling—which better justifies liking a child’s power fantasy.

This is not necessarily a bad thing: The Dark Knight and Logan remain my personal favorite superhero movies, likely in part because they renew inherently silly concepts with modern context and a deeper complexity. Matt Reeves appears to simply be going farther in this direction with The Batman, a film that may also be as far removed from the dry sense of humor of Bale’s Bruce Wayne as Affleck’s was. But judging by only a teaser trailer, it’s a movie so committed to its vision of Batman as a noir hero in a broken city, and not a blockbuster spectacle, that its director won’t need to tweet anyone that this is for grownups.