Historical War Epics of the 2000s Ranked

We revisit the 2000s, a time when historical epics became big business again, and rank them from worst to best.

“There was once a dream that was Rome. You could only whisper it, anything more than a whisper and it would vanish.” These were the words spoken by Richard Harris at his most regal in Gladiator, adding some blockbuster poeticism to the democratic ideals of the Roman republic—a dream lost long before Gladiator begins. But he could just as easily be speaking about the beauty and grandeur of the historical epics which inspired Gladiator .

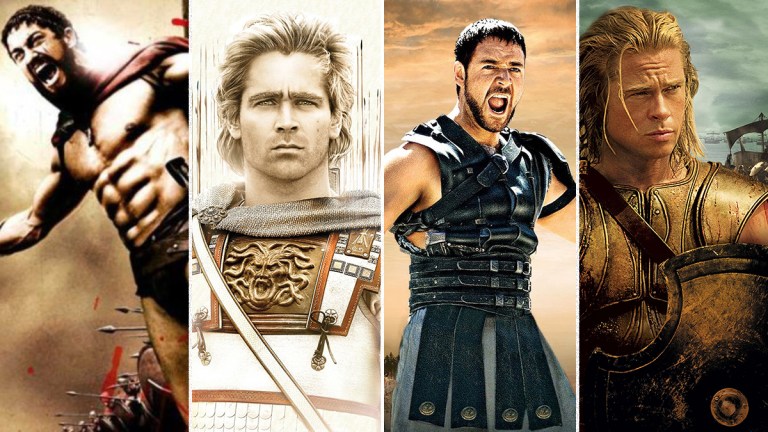

Decades before Russell Crowe and Ridley Scott reawakened that whisper to a mighty roar, historical war epics, from swords and sandals beefcake cinema to Napoleonic and Revolutionary melodramas, were the order of the day in Hollywood. Kirk Douglas’ Spartacus and Charlton Heston’s Ben-Hur were the superheroes of the early ‘60s, before the genre’s popularity receded to camp TV miniseries ignominy. Then came Gladiator (and to a lesser extent Braveheart five years earlier), and the bloated Hollywood historical epic was back. Throughout the 2000s and early 2010s, muscular movie stars crossed swords, medieval chainmail was adorned, and Greco sandals were fitted. For a brief time in this century, bronze breastplates instead of capes were the costume of choice for Hollywood’s biggest leading men.

So with Gladiator turning 20 this summer, we felt it only fitting to rank the movies of that era from their worst to best. Note we are keeping this just to the movies released in the 2000s, but rest assured that if we included the final dregs of the early 2010s, Ridley Scott’s Robin Hood would be near the very bottom.

13. The Last Legion (2007)

The King Arthur myth remains a tantalizing conundrum for filmmakers in the 21st century. On the one hand, it is a set of legends so ancient they are all in the public domain many centuries over; on the other, no filmmaker or studio seems to know how to wrap their arms around them for a modern audience. Take for instance this dead-on-arrival action romp, The Last Legion. Three years after Disney’s more earnest attempt to remake Arthur in the blockbuster stylings of its day (more on that in a moment), Dino De Laurentiis produced this cheap, half-hearted failure that tried to find a middle way.

Centered on the dubious idea that Arthur is actually a Roman noble who’s come to save the Britons from themselves, and here is the son of the last Roman Emperor to boot, The Last Legion attempts to be a historical epic on a budget, but really plays like an expensive episode of Xena: Warrior Princess with Colin Firth standing in for Lucy Lawless. Granted this makes a certain type of sense given director Doug Lefler worked on that very show, but then that tells you everything you need to know about this less-than-magical experience.

12. King Arthur (2004)

One of the most obvious attempts to recapture Gladiator’s lightning in a bottle turned out to be among the worst in this misbegotten other “true story” telling of the King Arthur legend. Pivoting on this dubious marketing claim, Disney produced a movie which saw David Franzoni, the original screenwriter of Gladiator, take center stage without John Logan cleaning up his narrative lines and dialogue, and Clive Owen strike an unconvincing pose as a blockbuster leading man.

Loosely based on the final days of the Roman Empire’s rule in Britannia, the movie introduces Owen’s Arthur as a half-Roman officer who must reluctantly take his “Knights of the Round Table” (a dirty half-dozen) on One Last Mission™. It’s a development which bears a striking similarity to Tears of the Sun (2003), a movie Antoine Fuqua just happened to direct the year before helming this wannabe epic. Even with shots of Michael Bay-styled hazy spectacle centered around Hadrian’s Wall, and the unconvincing sight of Keira Knightley in blue war paint and leather straps as a pagan Celtic warrior—she’s Guinevere, by the by—there’s not a whole lot about this dull affair we would deem legendary.

11. Gods and Generals (2003)

This is a trickier one to include. While certainly a would-be historical war epic released in the 2000s, Gods and Generals is in earnest a prequel to producer Ted Turner and director Ronald F. Maxwell’s Gettysburg (1993). That earlier, superior film was a TNT miniseries, but it’s so enjoyable to history buffs that it eventually got a theatrical release… then came this.

If Gettysburg flirted with Southern Lost Cause revisionism, then Gods and Generals married the insidious mythology, settled down with it, and produced a cinematic ne’er-do-well as its legacy. Like the title suggests, this movie deifies Confederate generals Robert E. Lee (Robert Duvall) and Stonewall Jackson (Stephen Lang) while completely sidestepping the reasons they were rebelling against the Union. It even incredulously features a scene where Jackson assures a Black man the Confederacy will one day emancipate its slaves.

Worse than any historical revisionism though, this movie is just a tepid slog across 220 minutes, with neither the budget nor cast of extras needed to infuse its battle scenes with a sense of authentic terror or excitement. Instead “both sides” are played by dignified, middle-aged reenactors who display no fears or self-awareness about sacrificing their lives for a cause the movie is too scared to accept.

10. Apocalypto (2006)

Ah, the first Mel Gibson entry on this list is also the picture he made after achieving brief godlike status among evangelicals and Tinseltown accountants via The Passion of the Christ (2004). With that level of box office clout, Gibson could do anything he wanted. So, tired of giving the British a bad look with his epics, he decided it was the ancient Mayans’ turn.

To be clear, there are elements to admire about Apocalypto. For starters, Gibson committed to having the actors speak in the Yucatec Maya language, an audacious choice for a Hollywood film. It really does create an irresistibly immersive quality. Dean Semler’s cinematography also goes a long way in forging a sense of reality to what is essentially a chase movie wherein ancient villagers of a remote tribe in Central America are conquered and then pursued by Mayans who desire to use their blood for human sacrifice.

Yet the sparseness of the story also makes it easy to get lost in visuals that seek to not only ‘Other’ the ancient past, but to also condescend to it in a movie that lazily equates Mayans and Aztecs as interchangeable; it was the latter who celebrated large scale human sacrifice of captured enemies. More troubling though is this seems intentionally mangled for the shock twist ending where we see the ships of Hernán Cortés arriving a full 600 years early, giving this movie the queasy realization that the whole thing is a cinematic justification for the conquest and violence of the Catholic Conquistadors.

9. Alexander (2004)

Behold, here lies Oliver Stone’s Waterloo. A testament to the filmmaker’s love for antiquity, Alexander is a big beautiful mess that cannot be saved no matter how many times Stone drastically recuts it. Indeed, there are three radically different versions of this well-intentioned ruin, but despite what the director says, none of them offer redemption. Still, it’s probably better than you remember.

With painstakingly accurate costumes designed by Jenny Beaven, gorgeous production design by Jan Roelfs, and extraordinary music by the always noteworthy Vangelis, there is a lot to aesthetically admire. But it comes to naught in this overwrought and underwritten melodrama with an Irish brogue. Yes, as mercilessly mocked in the press in 2004, star Colin Farrell speaks with an Irish lilt as the Macedonian conqueror. But hey no one is speaking ancient Greek either, so who cares? I’d argue the bigger problem is whatever Angelina Jolie is going for as Olympias, Alexander’s mother by way of Count Dracula.

More unfortunate is how Stone’s screenplay and direction reduces Alexander to a whiny, petulant, slob who bursts into tears at the drop of a toga. Despite the admirable choice by Stone to depict Alexander’s undefined queerness and love for another man (Jared Leto), one cannot help but sense the filmmaker is also relying on reductive stereotypes of the LGBTQ community to write Alexander while turning the life of a man who captured one-third of the known world into a bad soap where all he really wants to do is crawl into bed with mommy. But hey, the accurate depiction of battle tactics at Gaugamela is nifty.

8. The Patriot (2000)

One of the rare films on this list not influenced by the glut of battlefield glory spawned from Gladiator, The Patriot opened the same summer as an attempt to slyly remake Mel Gibson’s Oscar winning Braveheart in American Revolution garb. Keep in mind that both Gibson vehicles are gussied up revenge thrillers, ahistorical melodramas, and arguable propaganda intended to vilify a British Empire already quite susceptible to critique. In fact, the only significant difference may be Braveheart was directed by Gibson who, for whatever his other faults, is a hell of a storyteller, and The Patriot is helmed by the guy who gave us the Matthew Broderick Godzilla.

In between disaster flicks, Roland Emmerich took this brief stab at period piece respectability while indulging every hammy and histrionic Hollywood cliché. We have the reluctant hero in one Benjamin Martin (Mel Gibson); the wayward son who’s coming of age by proving he is exactly like the old man (Heath Ledger); and a generic British villain played by Jason Isaacs, whose nastiness errs closer to the Nazis in Occupied France than any specific Red Coat. Most incredulous though is that Gibson plays a South Carolina plantation owner who doesn’t own slaves. Yeah, that’s about as convincing as the rest of this laugh riot.

7. 300 (2007)

For many this is likely a movie where the memory is better than the film. Yes, 300 is loaded with ridiculously fetishized images of spears, corpses, and weird CGI deformities breaking like impotent waves across Gerard Butler’s chiseled abs. And sure, it spits out more quotable lines than Groucho Marx at a yacht club. But once you realize the best lines were taken from the actual historic record (at least according to Plutarch), and most of those shots already bopped in the much more digestible trailers, what we’re left with is a shallow, surface level video game cutscene that’s extended across two long hours.

In bite-sized clips, 300 can be an oblivious homoerotic gas, ready made for frat houses everywhere. Yet after a hundred minutes of Zack Snyder’s slow-motion ramping, and Butler screaming ferociously as he impales another inferior androgynous man with his flexing spear, it all wears a bit thin. It’s tendency to also indulge in fascist iconography of a godlike white civilization (that practices eugenics) shattering the faceless hordes of monstrous, dehumanized others hasn’t aged like fine wine either.

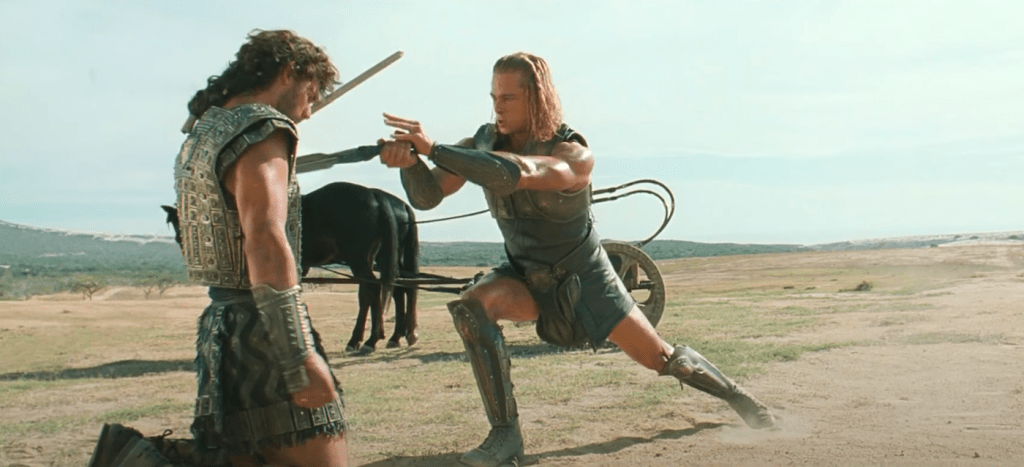

6. Troy (2004)

When 300 came out, many including myself found its CGI landscapes refreshing when compared to the hulking excesses of Wolfgang Petersen’s old-fashioned Troy. And 15 years later, the latter is still cheesier than Kraft blue box macaroni; Troy could even be mistaken for ‘50s kitsch if not for its own use of CG and copious amounts of gore and nudity. But now that Hollywood’s moved so far away from on-location shooting and grand scale moviemaking, all those alleged faults suddenly play like endearing virtues in this big goofy reduction of Homer’s The Iliad to an evening of WWE Monday Night Raw.

With a silly screenplay by David Benioff that does away with Homer’s gods, Troy lives or dies on its spectacle and charisma, and it’s got a thousand ships’ worth of both. Brad Pitt is at his hunkiest as Achilles, but the movie really belongs to Eric Bana as poor doomed Trojan Prince Hector. Essentially Benioff’s first attempt at writing Ned Stark before Game of Thrones, Hector is portrayed as a noble, ass-kicking lamb to the slaughter. Kudos also to Orlando Bloom for agreeing at the height of his popularity to play such an off-putting coward.

Still, it’s the superb action scenes that make Troy stand out. Unlike most contemporaries, Petersen shoots the action in steady, clean wide shots, revealing intricate and often dazzling fight choreography, as well as brutal smash ups between the Trojans and Greeks. With Peter O’Toole also on hand to give the movie just a passing sense of majesty as old King Priam, you can come for the thrilling Hector versus Achilles fight but stay for the aftermath where O’Toole kisses the hands of his son’s murderer. For a few minutes, Troy grazes its much desired greatness.

5. The Alamo (2004)

A film mercilessly mocked for not being remembered like its namesake, John Lee Hancock’s The Alamo deserves better. Easily more interesting than John Wayne’s 1960 snoozefest of the same name, The Alamo ’04 took the novel approach of dramatizing the actual historical record of the doomed effort to defend a Spanish mission-cum-fort from Antonio Lopez de Santa Ana’s army.

Hancock’s movie likewise uses a warts and all lens on its three heroes of William Travis (Patrick Wilson), James Bowie (Jason Patric), and David Crockett (Billy Bob Thornton), intentionally demythologizing all men, particularly the last one, while still giving Thornton several scenes of mythic quality. The actual siege of the Alamo is appropriately brutal and swift, if in a PG-13 sort of way, but it’s how Thornton plays Crockett serenading both the Mexican and Texan armies at dusk with a fiddle on a parapet that makes this movie poignant. Its qualities even overcome how tacked on the ending is where Sam Houston (Dennis Quaid) defeats the Mexican army at the later battle of San Jacinto.

4. The Last Samurai (2003)

Tom Cruise got in on the newest blockbuster fad of the current era, as is his wont, and did so with extreme conviction in The Last Samurai. The result was a satisfying and, at times, thrilling adventure picture that meshed Akira Kurosawa influences with the white savior storyline of Dances with Wolves. Problematic plotting aside, what makes The Last Samurai shine is the introduction of Ken Watanabe to American audiences as the true last Samurai.

Playing Katsumoto, a Samurai loosely based on the real-life Saigō Takamori, Watanabe dominates the movie all the way to an Oscar nomination as the lone warrior who will not get with the program. He rejects the rapid westernization of feudal Japan, much to the displeasure of his emperor and American and European patrons, thereby putting Katsumoto on a collision course with disillusioned U.S. Cavalry officer Nathan Algren (Cruise).

Nathan, by contrast, comes to Japan as a simple mercenary after years of bitter American Indian warfare, but he stays as a convert, adopting the Samurai’s code and fighting alongside Katsumoto in a doomed battle against the emperor’s army. It’s a familiar and ludicrous tale told with sincere grace and effective direction by Edward Zwick. Plus, the Samurai versus ninja sequence is just all kinds of badass.

3. Kingdom of Heaven (2005) – Director’s Cut

Most folks have never seen the Ridley Scott director’s cut of Kingdom of Heaven, which means most have never seen Kingdom of Heaven. Not really. There is of course a theatrical version, which in 144 minutes retains the narrative skeleton and action beats of the same story, but what’s missing is the film’s heart and much of its soul. When restored to its proper 190-minute length, Kingdom of Heaven is a visibly personal film to Scott, and an intoxicating one that gets swept away in a storm of medieval pageantry and pensive spiritual anxiety.

Loosely basing his film on the Fall of Jerusalem from Christian rule 1187—placing this between the Second and Third Crusade—Scott doesn’t care so much about historical fidelity as he does with creating a brooding snapshot of Western apprehension during the height of the War on Terror. He also makes a dense epic, captured in painterly cinematography and costumes, and stuffed with amazing performances. While Orlando Bloom is only serviceable as Balian de Ibelin, he’s surrounded by fantastic performers like David Thewlis, Brendan Gleeson, Michael Sheen, Liam Neeson, Jeremy Irons, and Alexander Siddig. Of special note are Edward Norton as King Baldwin IV, the Leper King whom Scott and screenwriter William Monahan mythologize as a philosopher shrouded by a silver mask, and Ghassan Massoud as Saladin. Between the empathy of these two highly fictionalized crowns, a true Kingdom of God could’ve existed.

The other standout that deserves special attention is Eva Green as Sibylla, the Christian princess who becomes queen. In the theatrical version, studio edits reduced her to a simple love interest; in the director’s cut she is touched with the tragedy of Medea and the madness of Lady Macbeth when her son (wholly excised from the theatrical cut) becomes king… only to discover he’s also contracted leprosy.

2. Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003)

In almost any other year, Peter Weir’s meticulously crafted Master and Commander would’ve been the toast of awards season. Sadly, it was overshadowed by the splashier third chapter of Lord of the Rings. Nevertheless, you’d be hard-pressed, even 17 years later, to find a more intelligent and well-anchored epic than this naval adventure. Set during the midst of the Napoleonic Wars, and loosely based on several Patrick O’Brian novels, Master and Commander immerses viewers into the daily rigmarole of life in the British Royal Navy.

While Russell Crowe is appropriately dashing as the long-haired British captain in search of a French prize in the Pacific, it is the effect of a perfectly cast ensemble that gives Weir’s movie a lived-in authenticity. Paul Bettany stands out as the smart-to-bordering on insubordinate Irish doctor, but there’s also Max Pirkis as the young midshipman with a touch of destiny, or Lee Ingleby as the much older mid-level officer with the scent of weakness and specter of doom trailing in his wake. Hell, the entire collection of hard-weathered character actors comprising the crew buoy this movie to greatness.

With an interest in naturalism that outclasses almost any other movie of its kind, Master and Commander breathes its sea air in full, and rises and falls like the cresting waves of its ship’s victories and defeats. Bettany’s poor Dr. Maturin may never get to spend enough time researching the animals of the Galapagos Islands in the film, but his story among men-at-arms makes for its own fascinating study.

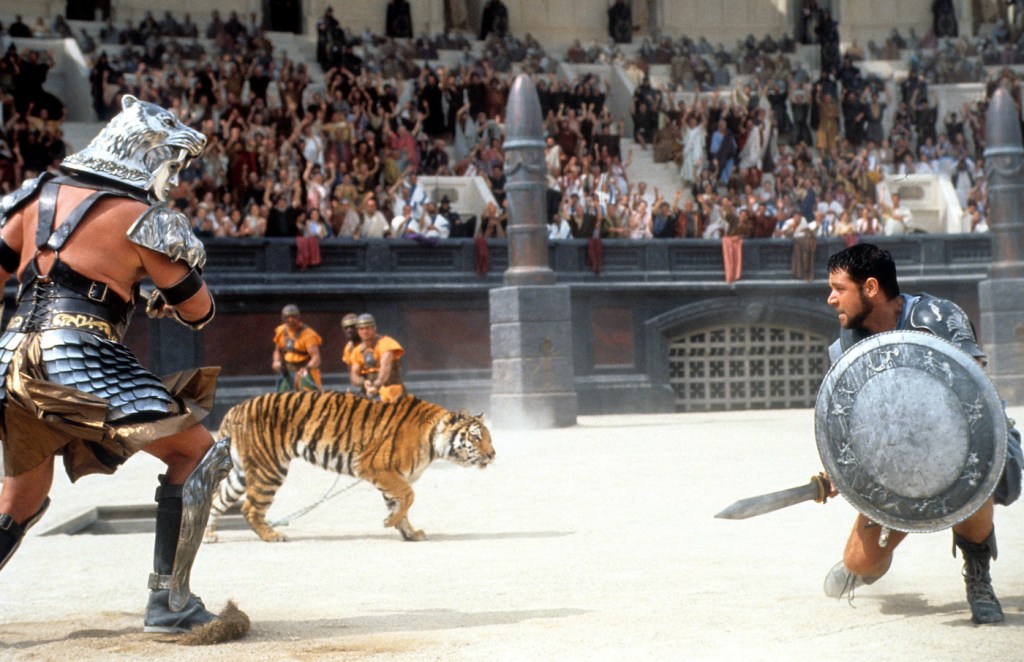

1. Gladiator (2000)

There is little that hasn’t been said about the glory and greatness of Ridley Scott’s Gladiator, but here is space to revel again in how this movie’s deeds echo through eternity. When the movie came out, debuting as an unlikely leggy box office hit and an even unlikelier Best Picture Oscar winner down the road, it had its share of critics who dismissed it as an action trifle. Yet Gladiator’s legacy has outlived those naysayers. To be sure the movie paints in archetypes, but it distills them to their most visceral and operatic extremes in a passion play about three people: the unwanted son (Joaquin Phoenix), the loved surrogate child (Russell Crowe), and the much smarter daughter who must survive them all (Connie Nielsen).

With these people setting their drama on a stage no less grand than the literal Roman arena, Gladiator elevates the revenger’s story into something poetic and lyrical, thanks in large part to its highly literate screenplay. Though getting there took some time, the end result allows Scott’s visceral instincts to bask in the Roman sun and sand, and gives much meat for all of the principles to play with, making stars of Crowe and Phoenix, as well as a gnarly ensemble of acting statesman like Richard Harris, Derek Jacobi, Djimon Hounsou, and Oliver Reed in his final, deliciously crusty performance.

Each of these elements build a sum greater than its already fine parts, leading to moments as satisfying as Crowe’s Maximus threatening Phoenix’s feckless Roman Emperor before an entire Colosseum, or as rapturous as Hans Zimmer and Lisa Gerrard’s transcendent musical score ushering Maximus into the fields of Elysium. It pities and romanticizes them all, even Phoenix’s unloved tyrant, but it also bakes them in a cinematic confection so rich that the tigers and gladiatorial mayhem is just a blood-red icing on top. There’s a reason it spawned a decade of imitators and aspirants.