James Bond Directors: A Complete History

Now that a director has been confirmed for Bond 25, we take a look back at the men who made 007.

This article comes from Den of Geek UK.

Directing a James Bond movie is pretty big deal. Bond 25 was thrown into chaos when Danny Boyle dropped out, and the news that Cary Fukunaga signed on to replace him has made headlines around the world. But it’s only recently that anyone actually cared who was behind the camera on a 007 film.

Partly because big name “auteurs” don’t often make franchise movies, partly because the Bond producers have always aimed for a kind of stylistic consistency to stop anyone putting a particularly big stamp on it, and mostly because 007 has always been more about a dozen other things that don’t have anything to do with the camerawork – most of the men (and they are all men) that made the other 24 films have been largely forgotten.

The current trend (possibly started by the Mission: Impossible series, and continued by Marvel, DC, and Star Wars) to hire named A-list directors to big studio franchises seems to be working well for everyone – but Bond built a lasting legacy on the back of journeyman filmmakers who knew how to handle action better than most.

You might have had to hunt for their names on the poster, but these are the men who made 007.

Terence Young

Dr. No (1962), From Russia With Love (1963), Thunderball (1965)

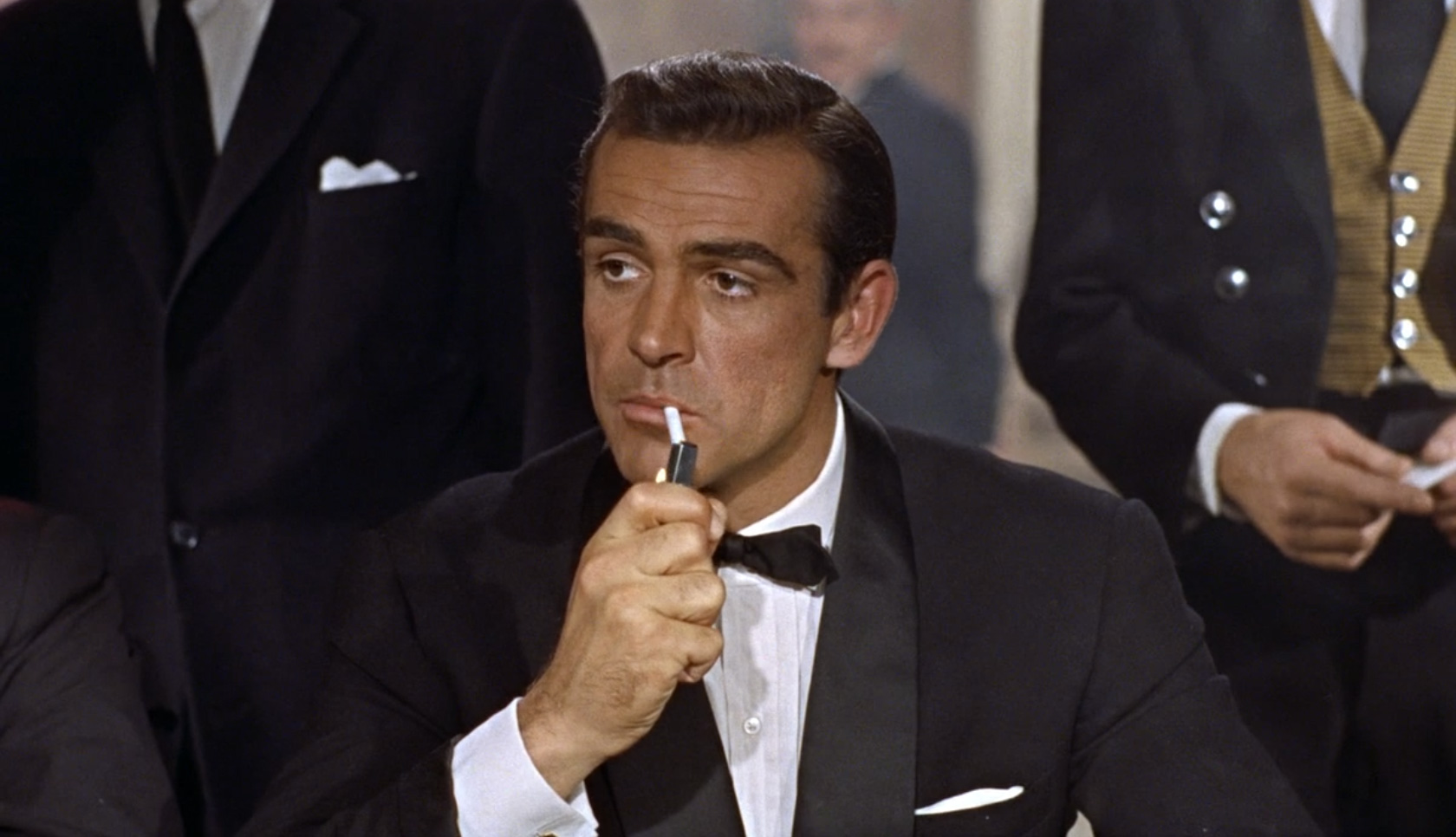

The man who made the very first James Bond film deserves a lot of the credit for everything that followed. With Dr. No (1962), Young established the tone that would roughly stay in place for at least the next fifty years – finding a balance between wit, charm and brute force that influenced a decade of imitators. From Russia With Love (1963) followed directly on – with Young asked back to manage a bigger budget in 1965 with Thunderball.

Young was actually a former intelligence officer himself (attached to an armoured division that saw heavy fighting in Normandy during WWII), and he reportedly became Sean Connery’s inspiration for the character – famously coaching him how to eat, drink, dress, and walk like a gentleman spy. Without Young, we wouldn’t have a big-screen Bond.

Unfortunately, after three 007 movies, one classy horror (Wait Until Dark) and several completely forgotten duds, Young made Inchon in 1982, which is widely regarded as one of the worst films ever made. More turkeys followed, and he died in 1994 with a bit of a mixed history.

Guy Hamilton

Goldfinger (1964), Diamonds Are Forever (1971), Live And Let Die (1973), The Man With The Golden Gun (1974)

Seeing Goldfinger, Live And Let Die, and The Man With The Golden Gun on his credit list, it’s easy to see Hamilton as the quintessential Bond director – the man who made three of 007’s best films. Arguably though, whatever makes those films great is more down to Connery and Moore (and Christopher Lee), with Hamilton leaning into campy comedy and steering the series away from its cooler, more stylish roots. This is, after all, the man who inflated Dr. Kananga over a shark tank until he exploded…

Hamilton played an important part in shaping the “fun” side of Bond – and of defining his whole early ’70s style – but his true legacy is as a director who was always one step away from greatness. Assisting John Huston on the set of The African Queen (not exactly an easy job), Hamilton directed The Colditz Story in 1955 and The Battle Of Britain in 1969. If he chose The Great Escape and The Dam Busters instead, things might have been a bit different for him… Almost directing both Superman: The Movie and Batman – his biggest success is still Goldfinger, and in giving James Bond a knack for sexual innuendos.

Lewis Gilbert

You Only Live Twice (1967), The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), Moonraker (1979)

Gilbert made two very important Bond films – refining and solidifying the characters that both Connery and Moore were working towards, and arguably giving both their best 007 films. Put You Only Live Twice and The Spy Who Loved Me side by side, and you get they best of Connery and Moore – making it all the more remarkable that they came from the same director. Clearly, Gilbert was a man who understood character (even he forgot it all by the time he made Moonraker).

Outside of MI6, Gilbert focussed on other character driven classics – making his name (and getting the Bond gig) with Alfie in 1966, but also turning in weighty, worthy dramas like Reach For The Sky, Carve Her Name With Pride, Educating Rita, and Shirley Valentine.

Peter R. Hunt

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969)

Peter Hunt only made one Bond film, but that wasn’t really his fault. Swap out George Lazenby for literally anyone else and On Her Majesty’s Secret Service is one of the best 007 movies ever made – and definitely one of the most visually interesting until the modern era.

Hunt was already a Bond veteran when he made the film – having edited Dr. No in 1962 and served as a Second Unit director on most of the others since – but On Her Majesty’s Secret Service was his first film as director. He made a couple of slightly forgettable gung-ho Roger Moore films afterwards (Gold, Shout At The Devil), along with two Charles Bronson revengers (Death Hunt, Assassination) and one awful sequel (Wild Geese II) before retiring the late 80s.

John Glen

For Your Eyes Only (1981), Octopussy (1983), A View To A Kill (1985), The Living Daylights (1987), Licence To Kill (1989)

The director with the most Bond credits to his name, John Glen made every 007 film of the ’80s – resulting in some of the worst entries in the entire franchise. This was the woolly jumper wearing, eye-brow raising, sluggish Roger Moore era that saw the likes of A View To A Kill become almost everyone’s least favorite film (including Moore himself, who later said “That wasn’t Bond, those weren’t Bond films…”).

further reading: It’s Time for the James Bond Franchise to Return to Absurdity With Love

On the up-side, Glen went on to make The Living Daylights and License To Kill with Timothy Dalton – ushering in the harder, grittier, more bombastic Bond era that spent the next 20 years trying to keep up with the Hollywood action trends. He didn’t really do much after 007 – although he did make a brilliantly odd turkey called Christopher Columbus: The Discovery, starring everyone from Marlon Brando and Tom Selleck to Catherine Zeta-Jones and Benicio Del Toro. Seek it out, if you can find it.

Martin Campbell

GoldenEye (1995), Casino Royale (2006)

Martin Campbell resurrected James Bond twice, which is quite the achievement. Starting out making cheeky British sex comedies in the ’70s (including one starring Christopher Biggins) before slowly clawing his way to the mainstream (via the Ray Liotta and Lance Henriksen classic, No Escape), Campbell directed the first, and best, Pierce Brosnan film in Goldeneye.

A big step away from Dalton at the time, Goldeneye was the first in the series that didn’t hang its script on a Fleming story, and it ended up feeling like the reboot everyone needed. Two Zorro films followed for Campbell, and he was asked back again in 2006 to reintroduce Bond for a second time with Daniel Craig’s Casino Royale. Smarter, darker, more sensitive and less quick with a quip – the sixth 007 felt like the biggest reinvention yet – leading us right up to wherever Bond 25 is taking us.

Edge Of Darkness, Green [cough] Lantern and The Foreigner followed for Campbell, with a long gestating adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s Across The River And Into The Trees rumored for the next few years.

Roger Spottiswoode

Tomorrow Never Dies (1997)

Back to Brosnan, Roger Spottiswoode helmed his second-best Bond outing (they get worse) marking the mid-point of one of the most varied careers around. Starting out as Sam Peckinpah’s editor on Straw Dogs and Pat Garrett And Billy The Kid, he went on to write 48 Hrs. for Walter Hill before making his directorial debut with the Nick Nolte and Gene Hackman thriller, Under Fire, in 1983.

After that, he tried pretty much everything from Robin Williams comedies (The Best Of Times), Tom Hanks classics (Turner And Hooch), harrowing war epics (Hiroshima), Arnie sci-fis (The 6th Day), family adventures (The Journey Home) and festive British pet biopics (A Street Cat Named Bob).

Michael Apted

The World Is Not Enough (1999)

Michael Apted was arguably the first really interesting choice of director for the Bond series – already acclaimed for television documentaries like the Up series, and for films like Coal Miner’s Daughter, Gorillas In The Mist, Class Action, and Nell. Known for his insightful work on the British class system, his ear for dialogue and his eye for stately, intricate drama, it was a bit of a shame when he came to Bond and made The World Is Not Enough.

Leaning back towards the cheeky humour and stuffiness of the worst parts of the Moore era, the film set Bond back a few decades when it tailored its entire final set-piece around keeping Denise Richards in a wet T-shirt.

Luckily for Apted, he brushed it off pretty quickly and went back to doing what he does best – making a documentary about Isacc Newton before he was even finished with Bond, and moving straight on to better films like Enigma, Amazing Grace, and The Chronicles Of Narnia: The Voyage Of The Dawn Treader. Next up, he’s currently prepping the landmark 63 Up, due for release in 2019.

Lee Tamahori

Die Another Day (2002)

Is Die Another Day the worst Bond film ever made? Probably not, but it’s definitely up there. Whatever went wrong with the film (the over use of CGI, the bit when Bond fights a load of laser robots, the confusing plot about gene therapy face swapping, the invisible car…), it probably wasn’t all Lee Tamahori’s fault.

Getting a lot of deserved attention for his Maori social drama, Once Were Warriors, Tamahori made the excellent film noir, Mulholland Falls, the decent survival adventure, The Edge, and the okay-ish thriller, Along Came A Spider.

After Bond, he moved onto XXX: State Of The Union (which was exactly the kind of film most critics accused him of trying to turn Die Another Day into), the awful Nicholas Cage sci-fi Next, and that film when Dominic Cooper tried to play an Iraqi (The Devil’s Double). In other words, he fizzled out. Thankfully, he went back to his roots in 2016 and made another brilliant Maori social drama with Mahana.

Marc Forster

Quantum Of Solace (2008)

Marc Forster was already very much a name by the time he made Quantum Of Solace – the slightly patchy, occasionally brilliant, opinion-dividing chapter of Craig’s Bond career.

Getting noticed for his indies, Forster helped Halle Berry to her Oscar win for Monster’s Ball in 2001, before scooping dozens of nominations himself for Finding Neverland, Stranger Than Fiction, and The Kite Runner. With no track record of handling action scenes (or big budgets), the producers took a gamble on Forster for Quantum Of Solace – and paved the way for him to make Machine Gun Preacher and World War Z. This year’s Christopher Robin has seen him back on quieter, more sentimental ground, with a drama about the formation of Greenpeace, and a Ewan McGregor led WWII epic, to follow.

Sam Mendes

Skyfall (2012), Spectre (2015)

We all know who Sam Mendes is, and that’s sort of the whole point – with his appointment to Bond meant to make us think the Broccoli family were handing over the reigns to someone with a real vision. Sure enough, both Skyfall and Spectre had visual flair to spare – exhibiting the kind of auteur flourishes that aren’t usually found in a Bond movie. The tone started to wobble across both movies (possibly prompting whatever new idea Boyle had, that Cary Fukunaga now has to reinterpret), but you can’t fault the way they look and feel.

Initially more famous for his work in the theatre than cinema, Mendes won an Oscar for his first film, American Beauty, picking up handfuls of awards for pretty much everything else since (Road To Perdition, Jarhead, Revolutionary Road, Away We Go). Leaving Bond in Fukunaga’s capable hands, he’s now prepping an ambitious WWI film called 1917 for Spielberg’s Amblin Partners. Expected out in the same year as Bond 25, it’ll be interesting to see where Fukunaga takes 007 next…

Further reading: The Acting Legacy of Every James Bond Actor