Toaplan: The Rise and Fall of Japan’s Greatest Shooting Game Company

All your base are belong to us! Known for Zero Wing, Toaplan made some of the best shooting games of the '80s and '90s...

This article comes from Den of Geek UK.

“Those 10 years were a time of great upheaval and change for us. Starting from nothing, we steadily brought more and more titles out, and then right at our zenith, it all fell apart, like a stone you’ve pushed atop a hill. I have so many memories of it all.” – Yuge Masahiro

To the backwash of an urgent, bass-driven soundtrack, the helicopter strafes left and right, its missiles reducing tanks and buildings alike to smoking, glowing ruins. The enemy returns fire, sending shimmering orbs of artillery careering back down the screen. With precise timing, the attack copter’s pilot weaves around the bullets, forging ever deeper through the battlefield.

This was Tiger Heli, a hit 1985 arcade game that, for many of us in the west, marked our first exposure to the work of the Japanese developer, Toaplan. Not that Toaplan ever became a household name like Sega or Nintendo. For much of the ’80s, its work was released under the banner of such distributors as Taito or Romstar. But while Toaplan’s name would remain relatively obscure, its personal brand of vertically-scrolling shooting games was immediately recognizable. Whether they were military themed (Tiger Heli, Twin Hawk) or set in the future (Slap Fight, Truxton), Toaplan’s games were defined by their intricate enemy attack patterns, unique weapons systems, and catchy music.

Like so many Japanese arcade developers, Toaplan’s games leaped to wider attention thanks to a string of ports to computers and consoles. Most gamers in the UK probably hadn’t even seen or heard of Hishouzame, but they may have played the surprisingly decent ZX Spectrum port, called Flying Shark. Tiger Heli, Toaplan’s first hit arcade game, was even more popular on the Nintendo Entertainment System. According to Steve Kent’s Ultimate History of Video Games, Tiger Heli sold about a million copies in the US alone.

Then there was Zero Wing, the Sega Mega Drive shooter that, with its infamously garbled English translation (“All your base are belong to us…”), became an internet meme in the late 1990s. It’s unfortunate, in fact, that Zero Wing‘s awkward dialogue went mainstream in a way that Toaplan’s games roundly didn’t. The studio’s output was, overwhelmingly, marked out by its precision and attention to detail.

Tiger Heli provided an ideal showcase for the Toaplan style. Pitting a single helicopter against a scrolling battlefield of tanks, gunboats, and other military vehicles, its action had the kind of deliberate pace that could lull an unwary player into a false sense of security. It’s when the enemies fire off their first major volley of bullets that Tiger Heli really shows its teeth: for the time, the game’s obstacle courses of glowing orbs provided a deceptively steep challenge. Little wonder that Toaplan is credited with sowing the seeds for what would later become known as the danmaku or “bullet hell” shooter.

Not that Toaplan’s games ever felt cheap or unfair. Their action was pitched in such a way that, although the challenge was high, the speed of the bullets and logical design of enemy patterns meant the games always felt as though they could be beaten with practice.

Besides, Tiger Heli also introduced an idea that helped relieve any mounting player frustration. The touch of a second button unleashed a bomb that destroyed everything within the reach of its huge burst circle — a deeply satisfying mechanic that also added a hint of strategy to the shooting action.

“During development we kept asking ourselves how we could make things fun, and the bomb system was what we arrived at,” programmer and sound designer Yuge Masahiro once recalled. “We didn’t originally intend for it to be used by players as an emergency save. We added it as an aggressive, thrilling weapon you could use to turn the tables on the enemies with a single shot.”

If Toaplan’s games were aggressive and thrilling, then that might be because the designers behind them were unfettered by the constraints of focus groups or demanding bosses. Rather than come up with detailed design documents, game ideas would often be jotted on a single piece of paper and then read out to the rest of the team. If everyone liked it, they’d make the game.

The office culture at Toaplan was, if contemporary interviews are anything to go by, rowdy and unconventional. At least a couple of developers were into riding motorbikes. Worryingly, programmer Uemura Tatsuya once said that Toaplan was “the kind of company where someone needed bandages almost every day.” Other interviews allude to late-night drinking sessions, company trips that descended into bouts of nude swimming in rivers, and days where employees would simply refuse to work and go to the local pool hall or bowling alley.

Fortunately, though, Toaplan still managed to find time to make some of the best shooters of the ’80s and ’90s.

“Since it was a development company from the start, we were able to make the games we wanted,” Uemura later reflected. “In that sense it was incredibly fun. Though it might be why we went bankrupt…”

Toaplan’s casual style came from its roots as an independent developer. Beginning life in a small Tokyo apartment, the studio was formed from former members of another failing developer called Orca, a firm that made a few little-known arcade games before it collapsed in the early 1980s. A second company, called Crux, would also prove to be short-lived. Ultimately, it was Toaplan (which loosely translates to “East Asia Project”) that would finally take root.

From its founding in 1984 to the end of the decade, Toaplan’s team remained small and close-knit. Its two main programmers, Uemura Tatsuya and Yuge Masahiro, also wrote the music for their own games, which explains why the infectious, looping theme tunes were so integral to the action. Although Toaplan’s first couple of games were fairly low-key (a Mahjong game for SNK and a top-down action game called Performan), Tiger Heli put the company on the map.

Inspired by the popularity of such vertical shooters as Namco’s Xevious, Tiger Heli‘s distinctive military theme and ferocious action set it apart from its contemporaries. Where other shooting games felt relatively austere, Tiger Heli was brash and exhilarating. Enemies exploded in great balls of flame, leaving craters of fire and burning debris in their wake. Meanwhile, Umemura’s baroque score pounded away in the background, urging the player on.

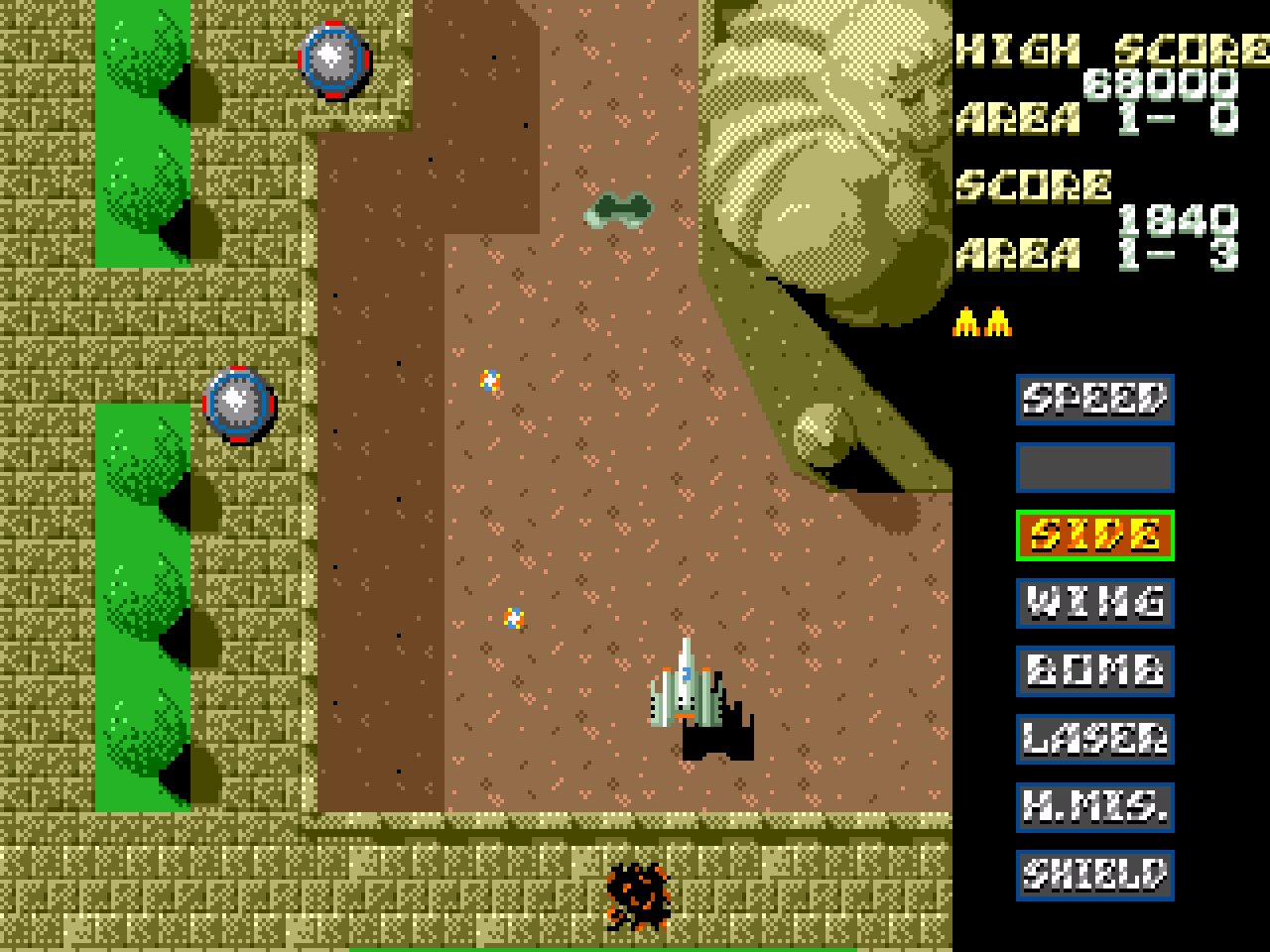

The immediate success of Tiger Heli allowed Toaplan to move from its cramped apartment to a dedicated office in Shinjuku, where the firm began work on an almost unbroken run of minor classics. Tiger Heli was followed by Slap Fight in 1986, a sci-fi shooter with an elaborate weapon system (cheekily cribbed from Konami’s Gradius) that offered a startling array of ways to kill unsuspecting aliens. Kyuukyoku Tiger (or Twin Cobra), released the following year, offered a turbo-charged update on the Tiger Heli theme, with another tiny helicopter going to war against an army of tanks and planes. Then came Tatsujin (or Truxton) in 1988, Daisenpuu (Twin Hawk) in 1989, and Same Same Same (Fire Shark) that same year.

Each game offered a unique twist on the Toaplan template, from the startling skull-faced bomb attack in Tatsujin to the awesome flamethrower weapon in Same Same Same. Most of them were ported to the Sega Genesis — largely because the console hardware was so similar to the arcade’s — making them some of Toaplan’s most widely-played games.

Not everything Toaplan made in the late ’80s was a classic, though. Wardner no Mori and Demon’s World were solid yet fairly forgettable platform games, while Get Star, a kind of scrolling beat-em-up released through Taito, was a commercial failure. All the same, Toaplan kept putting out games at a remarkable rate, with small teams of five or less completing a title within a span of about six months. This way, they were able to produce two or even three games per year.

With no corporate hierarchy to speak of, development at Toaplan was lively and sometimes chaotic. Rather than plan ahead, programmers would often just sit and experiment, creating a rough prototype with a controllable player ship. To this the designer would gradually add and test other elements, from new weapons systems to enemy attack patterns.

“There was never any systematic, organized method for [game development],” Uemura later admitted. “It was always totally disorganized.”

From that creative foundry came all kinds of unexpected game ideas. Zero Wing, for example, wasn’t even created with the goal of releasing it – instead, it was intended as a training project that new employees could contribute to and see how a game could come together.

“[Zero Wing] was created as a training project for our new hires,” Uemura recalled. “At that time we didn’t have any plans to release it commercially. But the decision to release it commercially made it a much more practical learning experience for the new developers, I think. On the other hand, the stage design and characters were rather cobbled together, so the world of the game was kind of a mess.”

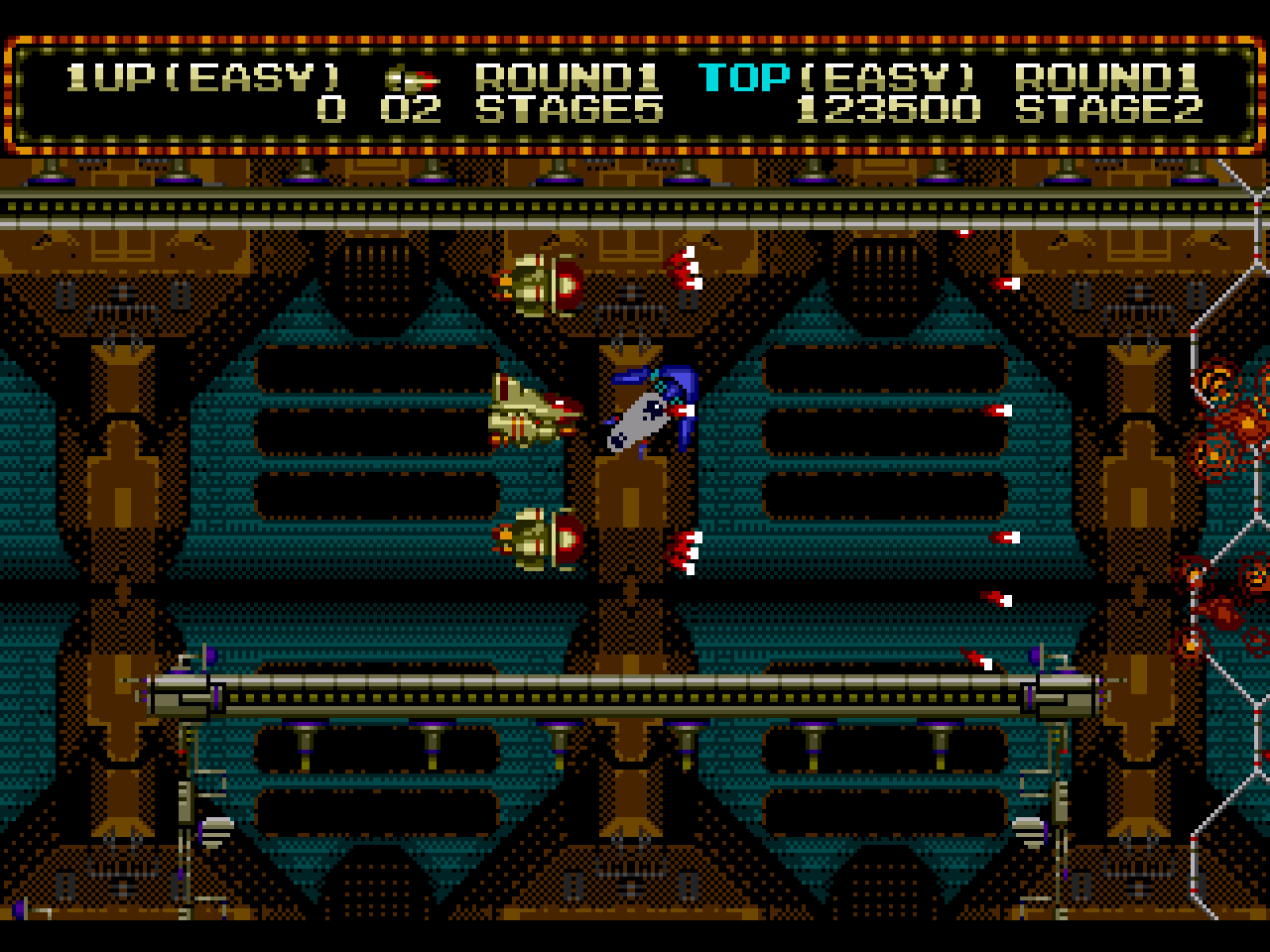

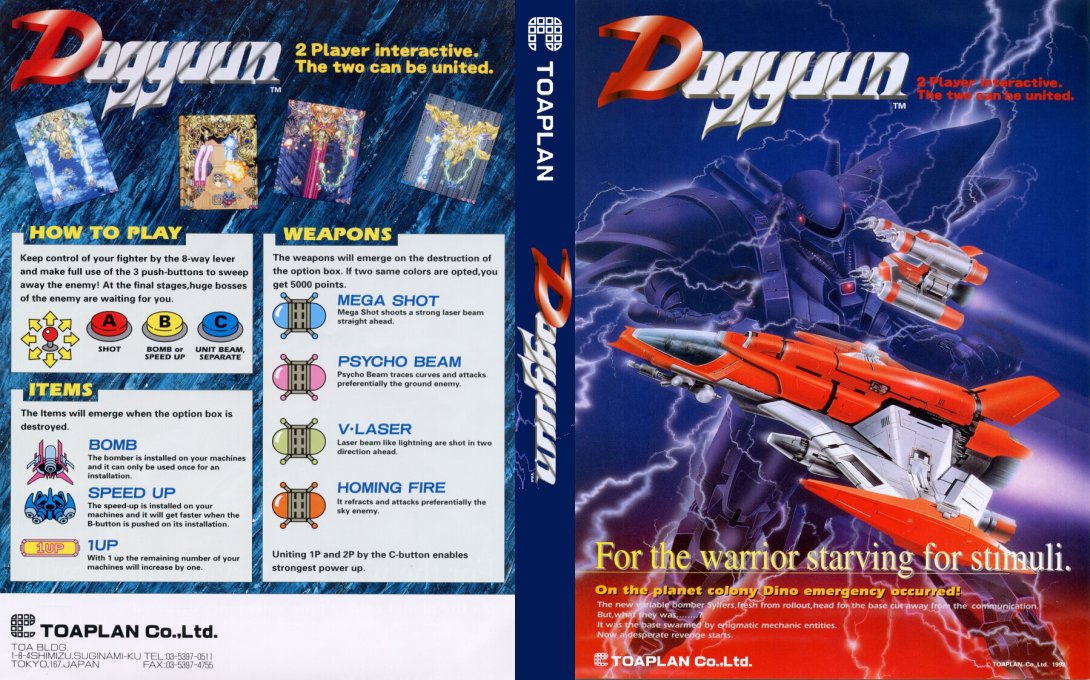

Zero Wing, along with the earlier Hellfire, was a rare foray into the world of horizontally-scrolling shooters – a subgenre that nobody at Toaplan seemed to particularly like. Indeed, while Toaplan often dabbled in other genres, from Bubble Bobble-style platformers (Snow Bros) to puzzle games (Teki Paki), it was its vertically-scrolling blasters that shone the brightest. As the early ’90s dawned, such titles as Dogyuun, Fixeight, and Grind Stormer (or V-V) pushed the template established by Tiger Heli and Slap Fight into ever more hectic arenas.

Ultimately, it may have been Toaplan’s lack of genre diversity that led to its downfall. By the early ’90s, arcades were dominated by one-on-one brawlers. As Street Fighter II exploded, the kinds of shooters Toaplan was making were becoming increasingly niche, enjoyed by the hardcore following who could keep up with their rising difficulty but falling out of favor elsewhere.

By 1994, Toaplan had gone bust — the unfortunate victim of a competitive and rapidly-changing industry. The brief spike of excitement surrounding Street Fighter II sparked a new golden age for arcade owners, but it would prove short-lived. The increasing popularity of consoles meant that more and more gamers were staying home. Game design itself was rapidly moving away from the quick-fix style of arcade games, designed to be played for a minute or two, and towards experiences with more depth. Street Fighter II may have delivered a blow to the 2D shooter, but it was the likes of Wolfenstein, Doom, and Quake that knocked the genre out of the ring, at least in the west.

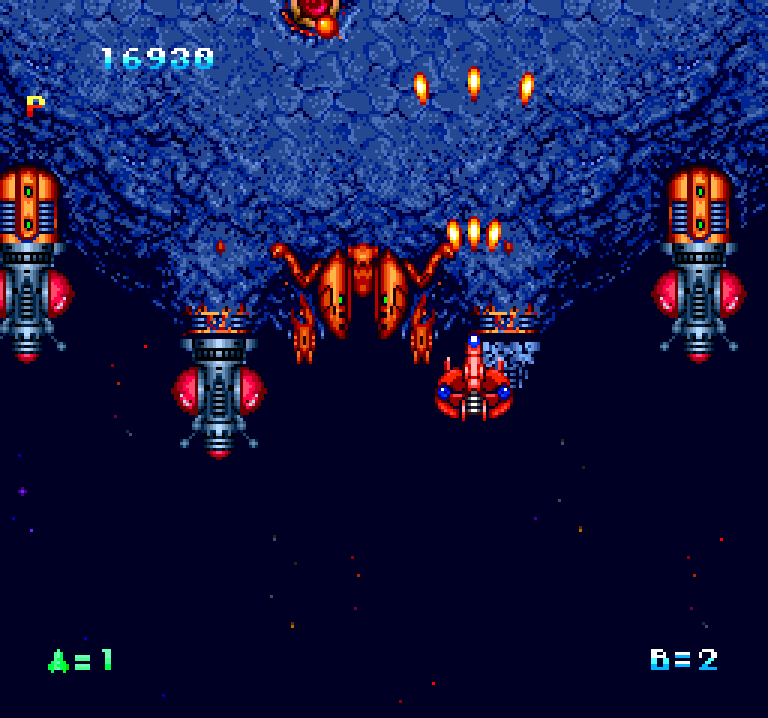

Batsugun, released in 1993, was Toaplan’s official swansong. But with its startling waves of colorful enemy lasers, Batsugun was also the beginning of a new era: that of the bullet hell shooter. As Toaplan broke apart, its former employees went off to found their own studios, and many of them continued to experiment in this increasingly berserk and niche field. Cave, founded in 1994, released the likes of DoDonPachi, Espgaluda, and Akai Katana. Gazelle didn’t last long, but survived long enough to make the extremely good Air Gallet (1996). Eighting produced the likes of Battle Garegga, Amed Police Batrider, and 1944: The Loop Master.

The bullet hell shooter has its own army of devoted fans, but it could be described as a different genre entirely from the tough yet approachable games that Toaplan was making in its heyday. As Japanese gaming celebrity Takahashi Meijin once told the magazine Shooting Gameside, “I wish they’d designate them as another genre or something. Make a distinction between ‘shooting games’ and ‘dodging games.'”

For those 10 glorious years, however, Toaplan created some of the greatest shooting games ever made. In a genre crowded with clones and knock-offs, their games felt distinctive, exciting, and fresh. Most of all, they felt rewarding and approachable where so many shooting games before and after seemed overly punitive or plain boring. Their games, although seldom cutting-edge from a technical standpoint, were made with evident care — from the truly bizarre aliens in Tatsujin to the sublime music in Twin Cobra to the wealth of hidden items in Slap Fight, they were full of style and personality.

Fittingly, Toaplan’s final game, Batsugun, has title that translates to “extraordinary” in English. If you loved shooters in the ’80s and ’90s, Toaplan was most certainly that.

Thanks to the fabulous Shmuplations for its wealth of translated interviews. If you love Japanese videogames, it’s a trove of information and history.