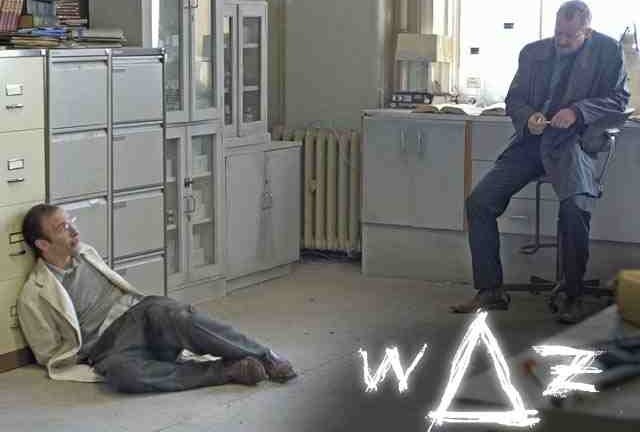

Waz director Tom Shankland interview

The director of horror-thriller Waz, out today, talks about Stellan Skarsgard, torture and altruism.

First-time director Tom Shankland has already been BAFTA-nominated for his short films, and makes his feature debut with the very dark thriller Waz, whose script invited the participation of the highly-respected Stellan Skarsgård…

Though I loved Waz in the end, I initially didn’t want to watch it, due to its implicit association with torture-porn – do you think this is the kind of thorny marketing issue that could keep it from its true audience?I was always very concerned personally that it wasn’t represented with any images that would put it in that kind of sub-genre. I think it’s going to be a challenge for them, to be honest. Obviously as far as I’m concerned, it’s an open house, with everyone welcome. But I always felt that the danger with that was that people on the look-out for a kind of smart thriller might enjoy it but might be put off if it was tagged with that slightly more…torture porn.

I would say that we nicked a lot of poster-ideas and image ideas that put it fairly firmly in that camp. Personally I would have gone for something cool and obscure – I like a bit of mystery in a poster myself.The film has been shown fairly extensively at festivals – how has the feedback been? I’ve heard of some at festivals who wouldn’t watch it because of descriptions of some of the violent imagery in the film.

With movies there are always going to be some people for whom it ain’t their cup of tea, but I have to say that what’s been great is that a lot of people have gone in thinking it’s not for them…and to be honest a lot of women have gone in fearing the worst, and have actually come out having found themselves a lot more emotionally involved than they might have been with another movie in that vein.

My take on it with the actors was that I always wanted it to be rich with emotional issues. Obviously you’re following fairly tight genre rules, but where there was the room for it, the aim was to get these emotional beats in there and give characters a bit of light and shade to make the audience feel a little bit of empathy.

Particularly with Selma’s character – we had long discussions about trying to humanise her as much as possible, so that while you preserve the scary aspect, you actually have someone there with a point of view that you can in some way relate to at some level.

A lot of people are assuming that Waz is Saw backwards…?

[laughs] Originally the script was called The Devil’s Algebra, but we weren’t crazy about that. The idea was worked on by me and Clive Bradley when we were at the National Film School in 2000. There was always this equation – which is a true equation, W-delta-Z, yada yada – and it was always altruism and this choice from hell in the two chairs.

That predated Saw by a few years, so that when Saw came out, we were gutted, saying ‘You fuckers! We had this idea!’. Obviously they’re different movies, but it was just this accident, this true equation. Clive, the writer, is obsessively trying to get everyone to call it W-Delta-Z, so that people don’t say ‘It’s Saw backwards’. I’m just thinking that’s a bit of a mouthful, and I’m gonna have to live with that.

Waz strikes more of a resemblance for me to the Blatty Exorcist novels. Were you concerned to say something about the nature of evil and love in this film?

That’s music to my ears. I went into it with the idea that what the theme was really about was whether love exists, and whether once you strip away all of our survival instincts and preservation instincts – is there something left? I felt that this was absolutely the kind of moral and psychological zone that I wanted to be exploring. Every decision I made about the look of the film was about trying to put that theme into the pictures. I wanted a city that felt unloved, and the lighting to have that slightly unloved, unromantic feeling – to get my characters walking around in this very broken down, dysfunctional landscape that didn’t have any safe corners, so that they were absolutely on their own as individuals. And had to work out all their answers for themselves.

I think that’s something that particularly appealed to Stellan Skarsgård. Having both feet firmly in European cinema, he’s never been a fan of scripts that have that slightly simplistic Hollywood version of life, where there’s good guys and bad guys and you’re either a villain or a hero. So he liked that we had characters that didn’t have that escape route into simple answers.

What was Stellan Skarsgård’s methodology as an actor, for you?

Stellan was pure joy, and very hard work in the best sense of the word. Stellan never ever allowed you to be bad. He would always say stuff like…with all the scenes in the torture chamber, he would sit me and Clive down and say [doing a good impersonation of Stellan Skarsgård] ‘Clive! This has to be as good as William Shakespeare!’ [laughs] You know, no pressure on the writer at all! His point was that if this was not going to be purely gratuitous, masochistic entertainment…the writing, psychologically, had to be right up there, to carry the audience through all that violence, because there is a kind of emotional reward in there, or a thematic reward.

So Stellan was really rigorous in the collaboration. But he’s the easiest actor to work with ever, because he has no real ego, no sense of it being ‘all about him’. He was tremendously popular with all the other actors, who all loved him because he’s such a talent, and invigorates everyone around him.

And he likes to drink and talk, like a good Scandinavian, so he’s always a lot of fun to be around. But one thing I must say about Stellan is that there’s nothing remotely ‘method’ about him, in the sense of searching his soul for sense-memories of guys he’s playing. He’s very technical and visual. He knows the effect of pushing a line this way or that way. He’s always thinking of the camera, so that makes it very easy to just talk about it technically and do another take. A real joy.

I’ve heard he had a fair amount of input as to the level of violence actually depicted in the film?

Yes, very much so. This was always going to be the tightrope that we’d have to walk. In order for the ending to be epic, there had to be enough depicted violence to give weight to the decisions and have the audience wondering what they would do in that situation.

Stellan’s concern. Which I enthusiastically supported, was that we wouldn’t repel the audience from the human drama, so at the end of the day these were three people in a room, working out their problems. There was a lot of debate about that while we were filming, and a lot of debate about that when we were editing. Inevitably I shot more violence than I actually used in the cut, because – though it’s a cliché to say it, the audience is always going to dream up something worse than we show them. As long as you suggest it enough, they’ll do the rest of it.

Did the need to disguise Belfast as New York contribute to the very dark and noir ambience of the cinematography?

Yeah, it was an absolute case of necessity being the mother of invention. We went to New York for about a week’s work and I got some good stuff there, but going there knowing that I had to shoot a lot of stuff later in Belfast made me do two things: one thing was that I started to turn a lot of scenes that were written as day scenes into night scenes. Belfast was fine for medium close-ups at night, and even for some wide shots, but any time your eye dropped off in the daytime, the illusion was gone.

But I got kind of excited about that 70s retro noir look, because I love those movies, so I was happy to be forced into that corner, and hopefully it made the look of the movie feel a little bit less like typical New York, but just a bit odder, a bit more skewed.

Were you conscious of the religious as well as the metaphysical ambience of the plot?

Yeah. I think Clive is quite an optimist about human nature in that way, but probably coming at it from quite an agnostic perspective, regarding the power of people having the capacity to make their lives better. So he would come at it from that place, that we have it in us to be altruistic.

When I was a kid I was always fascinated with the way the various saints were tortured or strung up on crosses or fired at with bows and arrows. I was brought up in Italy here and there, and my parents would drag me round five million churches. I hated all those bloody pictures of the Virgin Mary and her kid, but anything with St. Peter being strung up upside down or St. Sebastian being shot with arrows was really fascinating.

So I was always taken with the idea of what you would do for love. As a kid I didn’t understand it then, but I sort of got my head around the fact that they wanted that [suffering] for some weird reason. So I was invested emotionally in that theme from an early point, and the imagery of that idea excited me. But for Clive, it’s absolutely a statement about how he thinks the world is.

It’s the last kind of film that you would expect to be inspiring – it takes you through the absolute depths of human nature and leaves on a high note that you couldn’t possibly anticipate, even if you saw the plot-turn coming up.

Yes, and this was Stellan’s thing: he always said that he loved the film when he read it because it redeemed all the death, and it’s a great mash-up of emotions that you feel at the end. And this was what we were absolutely hoping that the effect would be.

Paul Kaye is also very good in Waz. What led you to that non-obvious casting choice?

We made the film with Vertigo, who’d made It’s All Gone Pete Tong. Every day I’d walk in the office and there’d be that picture of Paul Kaye in the Pete Tong poster. His character, Dr. Gelb, came into the story at a later stage because we felt that we needed someone to explain the formula, a cool, groovy mad-scientist red-herring. Maybe Paul got the producers to plant that poster there, so every day I’d walk in and just think ‘Hey, it’s got to be Paul Kaye!’.

Paul is actually a brilliant actor. We all know him from his comedy stuff, but he’s quite a serious and restrained guy, he’s got that mental look, so you can get him to play it quite straight and it’s still got that slightly skewed edge. I love Paul’s performance – he threw in quite a few very good ad-libs as well, for being the kind of actor that he is. A few of them have stayed in the film, as some favourite moments of mine.

Given success for the film, would you embrace or proscribe a sequel?

It’s very interesting. At the time I had no idea how you could do that…I don’t think I personally have much more to say on the subject of altruism right now.

Was transferring the story’s location to the US a purely commercial necessity?

We’d always thought that it could make that switch quite easily, right from the start of script development. The producers were keen on it, and it opened the project out as far as casting was concerned. To be honest I just felt that it sat more comfortably in an American universe rather than a British one, where…this might just be me not having enough imagination…what I’m doing at the moment is absolutely British-set and I’m loving that.

This would be The Day…?

Yes, and I’m revelling in this middle-class English horror-movie drama. But I just felt that with that sort of…serial killers and guns and grit, I just thought that New York’s got to be better than Peckham as a backdrop.

Waz is on general release now. Our review is here.

Check out the other interviews at Den Of Geek here.